Tôn Thất An is a Parisian born Vietnamese composer now based in Taipei, and has been writing for contemporary dance, theatre, film and art projects, and composing instrumental music as well as songs.

In the past four years, he has scored for a string of indie Vietnamese films: ‘The Third Wife' (2018) and ‘Between Shadow and Soul' (2019) by Ash Mayfair, ‘Song Lang' (2018) by Leon Le, ‘Goodbye Mother' (2019) by Trịnh Đình Lê Minh and ‘Ròm' (2019) by Trần Thanh Huy. He has also contributed to Naomi Kawase's ‘True Mothers' (2020).

He significantly collaborated with Japanese choreographer Jo Kanamori: ‘NINA – materialize sacrifice' (2005), ‘PLAY 2 PLAY' (2007), ‘Les Contes d'Hoffmann' (2010), ‘The Dream of the Swan' (2017) and with Taiwanese dance wunderkind Huang Yi: ‘Symphony Project' (2010), ‘Double Yellow Line' (2012) and ‘Special Order' (2014).

His work as a composer also brought him to the Philharmonie Hall in Berlin where he premiered ‘The Legend of Thánh Gióng' (2013), a symphonic tale commissioned by The Berlin Symphony Orchestra.

As singer-songwriter Aaken, he has made three studio albums: ‘Circlesong' (2005), ‘Hyperbody' (2010) and ‘We were (t)here' (2017). In Taiwan, he co-wrote and arranged songs of Sam Liao's award-winning album ‘Forgotten West' 西部 (2018), which garnered him the ‘Best Arranger' awards at the 2019 Taiwan Golden Melody and a ‘Best Album in Taiwanese' for Sam Liao.

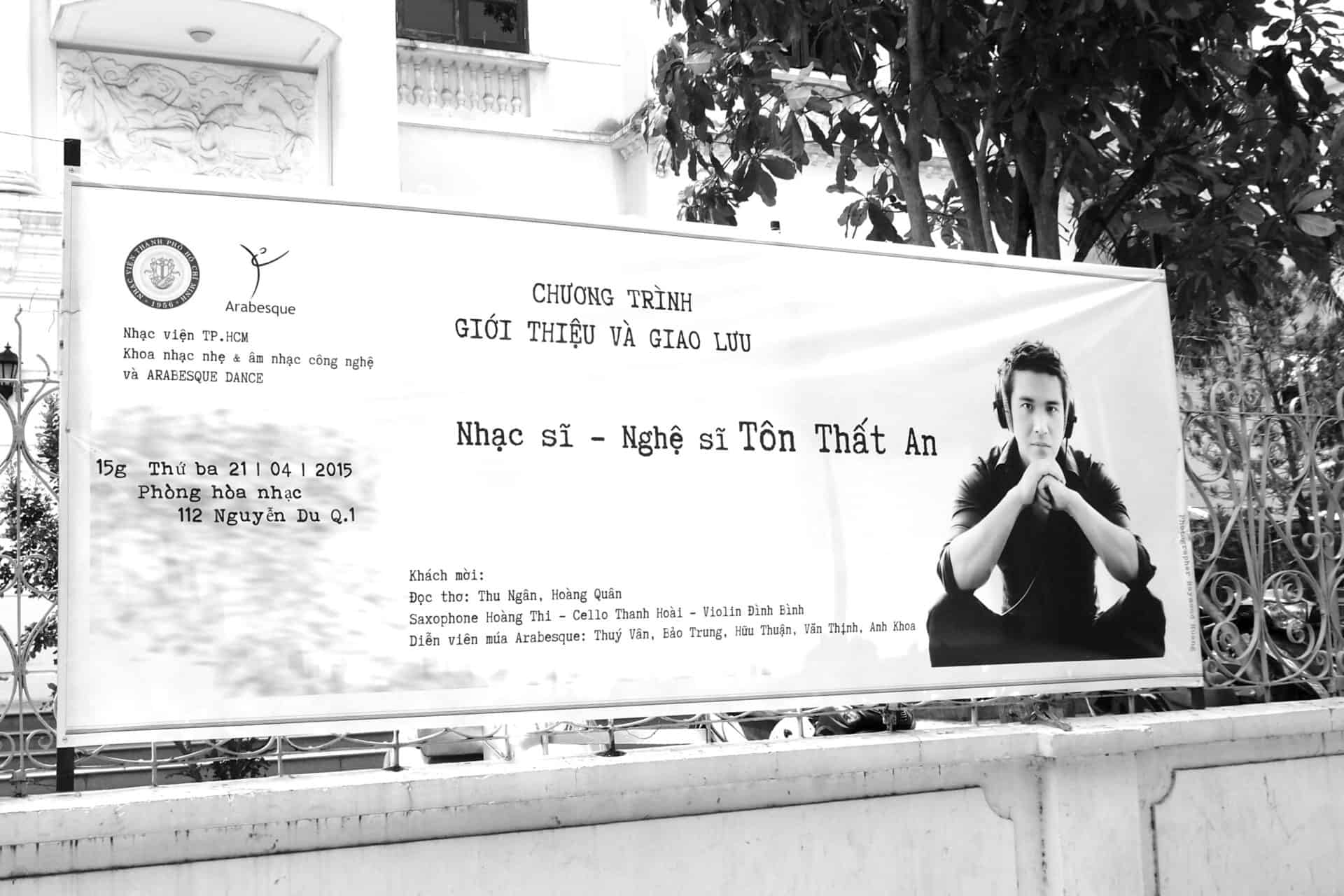

In 2015, he launched and curated the first edition of ‘[FEEL] in/out', an indie art project in Saigon with local Vietnamese artists, an immersive experience that blends performing arts, film, photography, music, dance and fine arts.

We speak with him about his many collaborations in cinema, his creative process, how his origin has shaped him as an artist and a person, his cooperation with Japanese choreographer Jo Kanamori and his company Noism and his future projects

‘The Third Wife', ‘Ròm', ‘Song Lang', ‘Goodbye Mother'… You have collaborated with Ash Mayfair, Trần Thanh Huy, Leon Le on a string of Vietnamese films. How was your experience working with them and in what way do they differ in terms of implementing music in their films?

These past four years have been a fantastic and intense journey for me. Until then, I had seldom written for film, just a few short films here and there. I was more active in the contemporary dance scene, so composing for a long feature film presented a very exciting challenge for me. The creative process is of course different from one film to another. But I generally was given lots of freedom by all the directors.

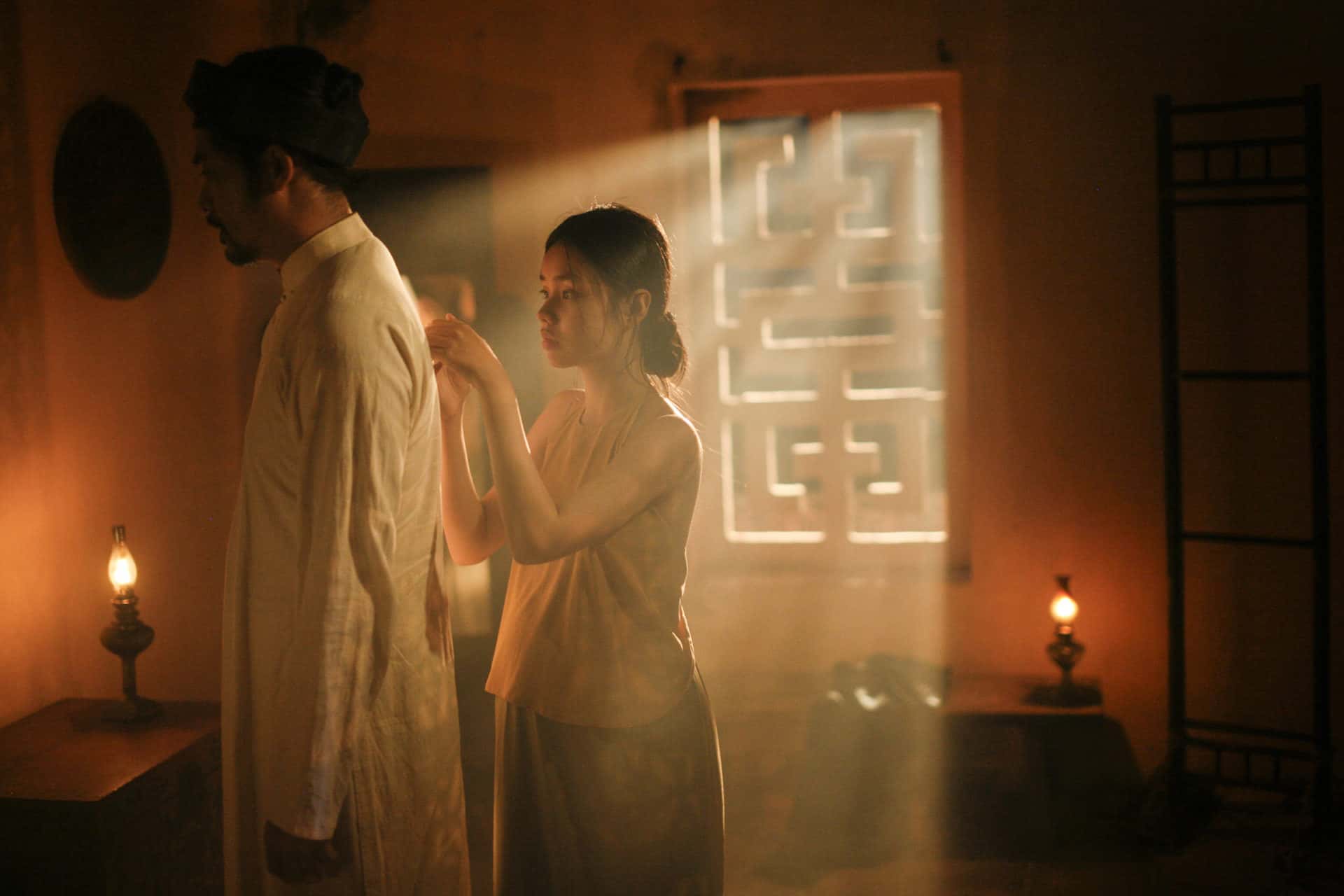

Trần Thị Bích Ngọc, the producer of ‘The Third Wife' has a great intuitive understanding of what a film needs. She contacted me at the beginning of the project, gave me the screenplay to read, and invited me to Ninh Bình (North Vietnam) to watch the shooting. That was ideal for me, as I could plunge into the atmosphere of the film, observe the actors and the crew, and of course, meet Ash Mayfair, the director. Even though the music did not have any shape yet, I immediately had a feel of how it would sound: electronic soundscapes combined with a small group of musicians (violin, cello, erhu, percussion, bamboo and sakuhachi flutes and piano). Ash just happily let me free to experiment. When they began editing, I suggested to get in touch with the editor Julie Béziau and sent her some of my previous work so that she could get acquainted with my universe. That actually helped her a lot. We would have long talks on the phone and she would then share some of her ideas. Julie is an extremely musical editor so I know that whatever she asks always makes sense. Once the first draft of the film was done, Ash came to France, and we worked together for a few weeks. On the other side of the planet, I was writing and writing – whatever would come to my head, and then send the pieces to Ash. As a result, I composed much more than necessary. Ash would pick certain pieces and use them in ways I had not thought of. There were many moments of magic, when some of the pieces I wrote without having seen anything, would fit a scene perfectly. Ash often said that it was the film that decided what was good for it.

Of course taking months like that is a luxury that we rarely can afford in filmmaking, as it is also rare for a composer to have the opportunity to attend the shooting and be in the project from the beginning. I was truly lucky for a first-timer.

For ‘Song Lang', on the contrary, there wasn't much time and in the film, I came into the project towards the end. Cải lương, a form of Vietnamese traditional opera, is central to the plot (one of the two main characters is a Cải lương performer) so the challenge was to find how the score was to intervene. When I watched the draft Leon Le sent me, I immediately felt an interesting aspect from the other character, Dũng “Thunderbolt” a taciturn gangster, who reminded me of film noir antiheroes. Therefore, I chose that direction as a counterpart for the Cải lương. I devised Dũng's musical ‘identity' by using moody and atmospheric electric guitars that would evolve towards something more lyrical with the cello, as the character develops. Leon's vision was very clear, and his requests were very precise – there wasn't much room for improvisation, yet he was ready to try different ideas as long as they worked for the film. For instance, he initially wanted to integrate Cải lương elements into the score, but I advised him to let the film ‘breathe', as we already hear quite a lot of it during the movie, to the point that for the climatic scene at the theatre, he decided to mute the Cải lương we hear being performed on stage to let the score take over and carry the audience emotionally. That climatic scene gave me quite a headache! I wrote up to five different versions until I nailed it. Leon is a great director to work with, as he is very respectful when he feels his collaborator knows his stuff. But don't even begin to slip any nonsense because then you'll have to fight a tiger!

Regarding ‘Ròm', I have to thank Trần Anh Hùng for thinking of me for the project. Incidentally, it was his wife Trần Nữ Yên Khê who suggested my name when Trần Thị Bích Ngọc was looking for a composer for ‘The Third Wife'. Both have been giving lots of their energy and time to support Vietnamese cinema and young emerging directors in the past few years (Ash Mayfair, Lê Bảo, Trần Thanh Huy…) In the midst of all the projects I was handling, I would mentally sketch some ideas for ‘Ròm' whenever there was any available space in my head and let them grow. If Trần Anh Hùng had a foresight about what my music would bring to the film, Huy was in a fog of uncertainty until the last moment! I guess I must have kept him walking on hot coal all that time! The score only materialised a couple of weeks before he came to Paris for the sound mixing. The day he arrived in town, I took him to Potemkine, a favourite spot of mine – a cinema shop which also functions as a café. I played him all the music I had written for his film. That lasted a full hour. It was great to watch him as he was listening to it. Once he was done, he remained silent for a while but had a big smile on his face. For some pieces, I knew exactly for which scene they would be used, for many others, I had composed them based on one of the characters, or an impression, and Huy found very surprising ways to use them.

I must say, the most challenging project was Between ‘Shadow and Soul', the silent/black and white version of ‘The Third Wife'. I had just finished working on the colour version and my mind was in no condition to imagine any music for the monochrome reworking of it. I'm partly guilty for it… A black and white picture I took during the shooting of the film triggered Ash's imagination, and next thing I knew, she was working on a black and white version of the film with Yov Moor, the colourist. She even toyed with the idea of only releasing that version, but a colour cut had already been sent to some festivals, so it was too late.

A couple of months later, Ash showed me the monochrome version. I liked it very much. Without the lushness of the colours, we were right at the heart of the human drama. It was a different experience, even though it was the same film. However, I found that black & white did not work with the music. Something was off. Ash believed that it was just a question of mixing. I wasn't so sure. Two weeks later, she announced that ‘Between Shadow and Soul' would also be a silent film! And it wasn't to be a conventional silent film either, as Ash wanted to keep the sound design. But somehow, the more restrictions one has, the further one has to go!

Being a French-born Vietnamese, how did this shape you as a person and as an artist?

I think it's been a long process of allowing the opposites and the disparate in me to co-exist. In my younger years, I wasn't fully aware of the notion of ‘being Asian'. I just knew I was very different from everyone else on many levels and I was this Vietnamese boy growing up in France and trying to feel at ease in his skin and be accepted. Looking back now, I'd say that it's about coming to terms with all the things that set me apart as ‘different', to understand what I was made of and be in tune with myself. Only then was I able to really create – that was by the time I reached my late twenties. And it was by that time that I went east and began to spend more and more time in various Asian cities to eventually settle in Taiwan. All my life, I had been very curious, an avid book reader, a passionate music and film lover. And once I was more aligned with who I was, opportunities began to come in the most unexpected manner.

Indeed, you are a singer/songwriter, a music arranger and an art director, you write music for contemporary dance and art installations… How does your way of working differ for each capacity? Where do you draw inspiration from, for all these works? Have you ever found yourself spent, experiencing an author's block?

My life is a series of what we would call ‘fortunate accidents'. Important turning points would occur when I was the least prepared. Since my life has always been very unstable, I developed the ability to improvise with what I had, just like a child playing. The same applies when a project comes to me. I often have no idea whether I can do it, but I welcome the opportunity. For instance, when the Berlin Symphony Orchestra asked me to compose a piece for them, I had absolutely no experience in scoring for orchestra – might as well have asked me to perform high-flying circus acrobatics! But I said yes. That was utter madness and I certainly had many moments of total panic.

Even though I am a classically trained musician, I am largely self-taught as a composer, so I rely a lot on my intuition which tells me where to go. In my everyday life, I'm like an antenna that receives and stores lots of information, images, sounds, thoughts, impressions, etc… which get selected when comes the time to create. So whether it is a song, a piece for dance, a film score, a short film, music for an art installation or when I curate and direct those art projects, my approach is similar. I go where my intuition/inspiration takes me, gather ideas and then structure what I have harvested. The hardest is to not let the mind take control and pressure me with thoughts of results.

When I am facing a blank page, I just do something else instead of forcing myself to produce something. Or I accept that it isn't the right moment, and I have a break. Last year, for instance, I was handling three projects at the same time: writing and producing an album for a Taiwanese singer, scoring for a documentary and the Naomi Kawase film. The only way I made it through alive was to be … like water.

Tell us about this collaboration with Naomi Kawase on ‘True Mothers'.

It was a very particular situation. There was already another composer on that film but she wanted to expand the palette of the music, so Roman Dymny (who did the sound for several of Naomi Kawase films and who had also worked with me on ‘The Third Wife', ‘Between Shadow and Soul' and ‘Ròm') suggested my name. They called me in the middle of the night and requested an emergency video conference!

Naomi-san makes me think of a deity on Earth. At the same time, she is very anchored to ‘real' life. When I began work on her film, she was busy finishing the editing in Paris. Communication was essentially done through video conferences. I asked she let me be free to do what I had in mind. She only insisted that I brought more radiance into the music. She was more than a tad destabilised when she heard for the first time…

I don't have enough words to praise Roman. You asked me about my collaboration with the directors, but my time in the studio with Roman was a revelation for me. He's such an intuitive sound magician. There's no way I would have been able to handle all the work for ‘True Mothers' if it weren't for him. We are on the same wavelength. He immediately gets my intentions. I had two weeks to write the whole score, then flew to Tokyo for the sound mixing: in only three days we had to mix and edit all the music into the film!

You know, when I watched ‘Still the Water', I was particularly struck by how organic and sensual its sound design was. When Ash announced me that we would be having a great sound designer for her film named Roman Dymny, I did some research and realised that he had worked on ‘Still the Water'!

Speaking of Japan, one artist you have collaborated with repeatedly is choreographer Jo Kanamori, and his company Noism. Can you give us some more details about this collaboration?

Jo Kanamori is my soulmate, artistically. The story began in 2004, when I attended his performance with Noism at the Maison de la Culture du Japon in Paris. I was simply mesmerised by what I saw and also felt a strong kinship with his artistic expression. I thought to myself that if there were one dancer/choreographer I would collaborate with, it was him. One year later, I was in Japan and decided to go meet him in Niigata, where his company is based. I gave him a CD of my current work, which he listened to. First contact was established. Things started to shape up a few months later when he asked permission to use one piece from the CD. Then a couple of weeks later, he invited me to collaborate on a full scale dance piece, ‘NINA – materialize sacrifice'. That work was a milestone for both of us. Noism got to tour around the world with it, and consequently, people heard the music and took notice.

The creative process was almost surreal. I was in Paris and he in Niigata. He would tell me his intentions for each movement – a few words as clues, and I would let my intuition guide me. For each newly composed movement, Jo would write back in awe and say that it perfectly matched what he had choreographed. In turn, when I came to Niigata for the rehearsals, I was absolutely stunned by how dance and music espoused each other, how each movement of the dancers seems to materialise into sound – or vice versa. Jo does have a sixth sense for music!

The ballet that I am particularly fond of and proud of is ‘PLAY 2 PLAY', which had the audience sitting on either sides of the stage. The set design was created by Japanese architect Tsuyoshi Tane, a set of ten triangular moveable glass towers which, depending on the light, would function as a gate or allow the audience to see what is happening on the other side of the stage. The music was a through-composed piece of 70 minutes. For that show, I also created a sound installation in the theatre so that people would get immediately immersed in the atmosphere. Working with Jo Kanamori is always a highly gratifying experience. Our last piece, ‘The Dream of the Swan' was in 2017. I hope the next time will be soon.

And now, what are you current and future projects?

I just completed work on two documentary films: ‘Rain in 2020' by Myanmar director Lee Yong Chao. Did you see ‘Blood Amber'? It's gorgeous! His documentaries are like poems. The second film, ‘Displacement_a quarantine hotel' is by Taiwanese director Jay Chern and follows the staff and guests of a quarantine hotel in Taipei and of course, its owner, who commissioned the film. For that one, I also took part in the editing and it was great fun! Hopefully those two documentaries will find their way to some festivals. One can never be sure how now…

And as for now, I'm currently composing for a film by Malaysian director Edmund Yeo. He managed to shoot it last winter in Tokyo!

After that… some personal projects, songs for a new album, keep on with my second experimental short film, a third edition of the indie art event [FEEL] in/out in Vietnam, perhaps an online version… Ash Mayfair is preparing her second feature ‘Skin of Youth' and Trần Thanh Huy is getting ready for ‘Tick', but those two films won't happen before next year.

Who knows who, who knows what… Life is a constant improvisation!