Before signing up with the Shaw Brothers and indulging in films that ranged from exploitation to hard-core porn (and kid movies somewhere between), and just after graduating from the National School of Arts, Mou Tun-fei shot two films, both of which were banned in the country: “I Didn't Dare to Tell You” and “The End of the Track”. As at the time, Mou's work was highly influenced by his mentor, Pai Ching-jui, who has returned from film studies in Italy, both these movies exhibit intense similarities with Italian neo-realism, which Pai got familiar with while abroad and passed on to his student.

I Didn't Dare to Tell You is screening at Electric Shadows Asian Film Festival

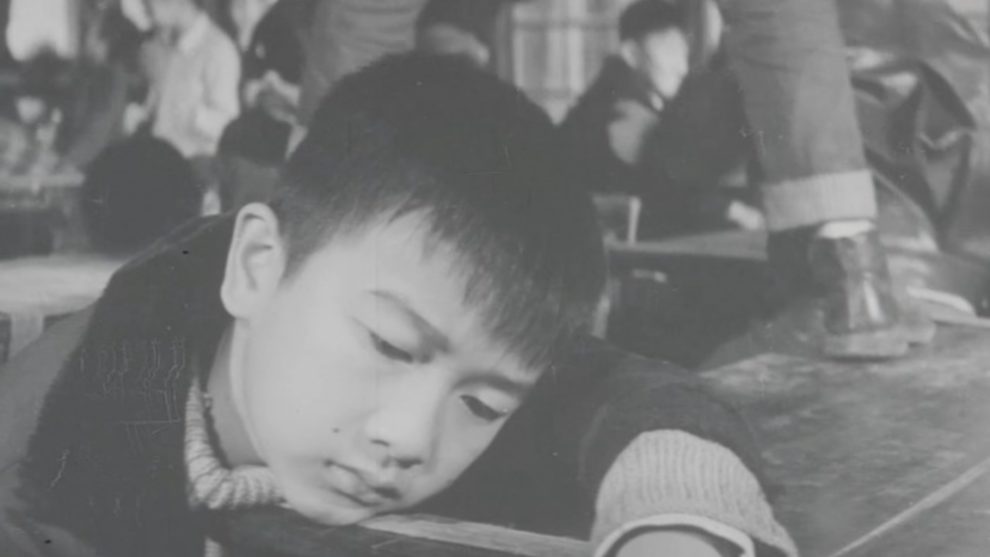

The story focuses on Dah Yuan, an elementary student who lives with his father, Chang, since his mother died some years ago. Chang is hard working, but has a gambling problem, which the local bookie, who also runs a funeral house, exploits to the fullest, making him agree to give him Dah Yuan as his apprentice, in order to pay off his debt. The rather poor father is being tortured by this agreement, which, along with his overall rather dire financial situation, make him constantly enervated, frequently lashing violently to his son. Dah Yuan has his own issues at school, since he is bullied and is not a particularly good student, since he prefers spending his time in a hideout of sorts he has built in a factory that processes wood. Eventually, Chang declines giving his son from such a young age, which would essentially have him dropping out of school, and instead decides to work more to pay off the debt. Dah Yuan, with a help of a friend who works at a local factory, gets a night job there, while his friend also helps him with his lessons. A girl from the classroom also hangs out with him providing as much support and logic as she can.

The second axis of the narrative revolves around Dah Yuan's teacher, Pai, who, as the film begins, is as strict and unforgiving towards her students as possible. However, the influence of her hippy-like, artist boyfriend, eventually changes her completely, particularly after he breaks her glasses and demands from her to let her hair loose, in one of the most memorable scenes of the movie. A bit later, and after another talk about not writing out students who get bad grades, Pai decides to pay more attention to Dah Yuan, eventually realizing his misery.

Through the two intermingling axes, Mou Tun-fei manages to tell both a very intriguing story and to make a number of social and political comments. Regarding the first aspect, the most obvious trait of the movie is the characterization, which shines both due to Rong Huang-gui's writing and Mou Tun-fei direction. Dah Yuan, the little boy who finds himself working at nights and falling asleep in classroom, the bitter father with the gambling problems and the violent fits, the teacher whose transformation from an uptight intellectual to a more carefree, caring individual and educator make her a better person are all impressively depicted, with the narrative revolving around them. This aspect also benefits the most by the acting, with Yu Jian-sheng as Dah Yuan giving a rather mature performance that netted him the Best Child Star at the 1970 Golden Horse Awards and Gua Ah-leh as Teacher Pai highlighting her transformation in the most eloquent manner. Particularly the scene where she smiles and laughs with her students for the first time, is another of the most memorable in the movie.

The same artfulness applies to the peripheral characters, with her wise mentor-boyfriend, Dah Yuan's two friends (the hard working boy and the wise beyond her years girl) and even the nosy neighbor which eventually becomes a catalyst to the story being both well written and acted.

The intermingling stories of all the aforementioned bring us to the second trait of the movie, that of the sociophilosophical commentary. Pai mirrors Mou Tun-fei's ideas about education, and the blights of the archetype of the strict and insensitive teacher that was the rule at the time, but the movie also deals with the issue of judging people without really knowing them, the harsh life of the poor in the country, single-parenting, gambling, and the people who exploited the poor. All of the aforementioned are excellently implemented into the narrative.

Through both the stories and the comments, the movie takes a path that leads very close to the melodrama, although Mou manages to avoid the reef of forced sentimentalism, almost completely. The ways he achieves that are many and multileveled. One of the most subtle is the slight comedy, mostly revolving around the children in the classroom, with the sequence where the class bully comments on women always being eager to please men just before he shows the same eagerness to help the teacher and receives the same kind of comments from a female classmate, is a testament to this approach. Furthermore, the presence of the artist and his relationship with Pei, which seems to prove the rule that “opposites attract each other”, is also presented in delightful fashion, with the same applying to Pei's transformation, which also allows for Gua Ah-leh's evident beauty to become a part of the narrative. Furthermore, the music-video like montage of her having a good time with her students also provides a rather entertaining relief, while the finale is anything but melodramatic. Lastly, the overall technical aspect and particularly the frequently sudden cuts, the framing and the lighting exhibit a kind of styless style that was one of the trademarks of neo-realism, and allow the movie to get away from formulaic sentimentalism.

The aforementioned, however, do not mean that the drama is missing, with particularly the things Dah Yuan has to endure from both his bullying classmates and his father being elements that move directly towards this path. Particularly the scene where the inevitable violence eventually erupts is truly shocking, with its realism adding to the drama even more, although Mou allows for a rather intense relief with the actual finale.

“I Didn't Dare to Tell You” is an impressive film, that has aged well both contextually and technically, and a very interesting watch that also benefits by its duration, which does not even reach the 80 minutes limit.