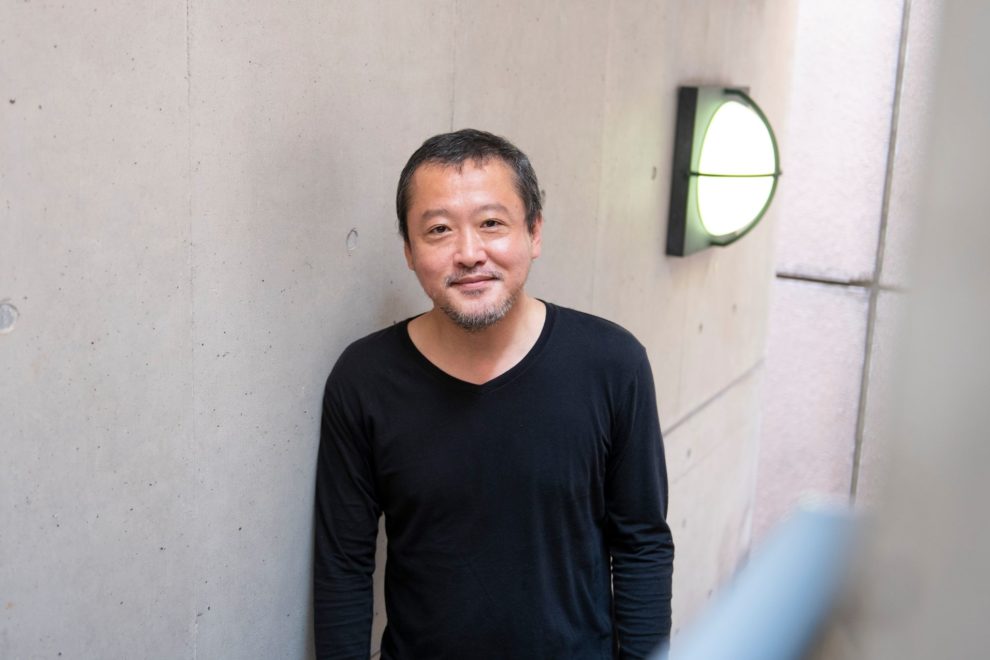

Yohta Kawase was born on December 28, 1969 in Kawasaki, Japan. He started his career as assistant director to Shozin Fukui in the 90s, but soon turned into acting. Currently, he has more than 150 films under his belt, most of which belong to the pinku genre. His latest works include “Blank 13” by Takumi Saitoh, “Demolition Girl” by Genta Matsugami and “A Balance” by Yujiro Harumoto, which premiered at the latest Berlinale.

We speak with him about his prolific career, acting in pink films, Takahisa Zeze, Yutaka Ikejima and Daisuke Goto, the latest generation of Japanese directors, his latest work, “Rageaholic” and many other topics.

Translated from Japanese by Lukasz Mankowski

You started your career in pinku films and you have won many awards for your performances. How did that come about and how was your experience of acting in those films? Was it difficult acting in all those sex scenes?

I actually started as an assistant director at the set of Shozin Fukui's indie film “Rubber's Lover” (1996), but soon enough he asked me to try playing the lead part. That's how it started. Back then, there was almost no distinction between crews from independent and pinku films, as the staff and cast would work on both of these productions. One day, I was invited by Takahisa Zeze to play in his project and that's how I entered the world of pinku film. As for shooting pinku films in Japan, the most difficult part is shooting the sex scenes, because showing genitals is illegal. The biggest struggle is then acting with your crotch hidden by a stripe of material (a tape that is used for medical purposes) so that the camera won't see the genitals. When I debuted at that time, it was the beginning of the DCP era. I think I did well with the sex scenes, but my acting was no good whatsoever. The other pain was acting with other people. There were many actresses with whom I had to play with, who had no interest in films at all (in the 90s many people working in pinku films were random people scouted on the streets or women working in sex shops), so the dialogues were often missed quite badly. There was one movie with a cutback scene during which the actress couldn't remember the lines, so the script would be attached to my chest in pieces, and she would read the monologue from that. My background is originally being an assistant director, so these peculiarities of being at a film set used to amuse me back then, but that also helped me navigate around all these jobs in the pinku industry.

How does the casting work in pinku films?

Male actors usually have a background in small theatre groups or, like me, they start from doing some indie films. There are many cases like that. As for women, I answered it a bit in the first question, but since it is a genre that requires playing naked, till the late 90s scouting took place on the streets or in underground theatre plays. Many times the actresses were nude models or had experience playing in adult videos. Currently, adult videos are quite popular in the porn industry, so most of the talent is chosen from adult video star actresses.

You have cooperated with Takahisa Zeze repeatedly. How would you describe him as a director and as a man?

Takahisa Zeze started his career as a pinku filmmaker because he admired the legends of the industry from the 1960s-70s, such as Koji Wakamatsu and Masao Adachi. Pinku-eiga are films that include regular and obligatory pornographic representation, but as a matter of fact, it is also a medium that grasps radical political opinions, which is absent in regular porn. I think that Zeze was really fond of that freedom, that he could be political in his films. The first film that I took part in as a pinku actor was Zeze's production, and one could feel the freedom in there, that it is not only the sex scenes that were proof of this freedom, but that there was a space to express anything.

Zeze went from pinku films to non-erotic ones and so did you. How was the transition?

I don't actually have a feeling that I went from pinku films to regular ones. And I think it is the same with Zeze. Even now, if I have the chance to act in pinku films, I do it. Zeze once told that “There are no borders in the film world anymore.” I believe so, too. Japanese Cinema industry is currently extremely divided. What is produced is either manga or literature-based films, as well as big-budget productions or indie films. And probably it's the same elsewhere in the world – you either work at epic enormous projects, where freedom is non-existent, or you have freedom, but you work on a small, independent film. But, pinku films are in the same category as the latter ones – they belong to the indie world. That's why, whenever I have the possibility, whenever my schedule allows me to, I still work for all of that: pinku films, indie or major films, TV work, and even student's small projects.

You have also cooperated repeatedly with Yutaka Ikejima and Daisuke Goto. Can you give us some details about your cooperation?

Not long after I started my career in pinku films, it was Yutaka Ikejima who offered me the next role. I consider myself quite a cinephile among the actors, so whenever I meet someone I ask about the films and opinions: “Have you seen this or that?” or ”I think this movie was a total disaster, what do you think?”. What's incredible about Ikejima is that he cares not only about old classics, such as Ozu, Mizoguchi, or Capra, but he still manages to watch plenty of recent films made by young directors. Daisuke Goto is also a film buff, but on top of that, he actually has an incredible love for screenwriting. For instance, in “Blind Love” where I acted, he came up with a story of a blind girl falling in love with the voice of a ventriloquist who happens to be very short. But, the story goes on with the girl having sex with the apprentice of the ventriloquist, who is tall, because she mistook him for her love. When the blind girl is about to have sex with the ventriloquist's disciple, the master, who's next to them, crying, pretends that it is him and plays along with his voice, because he didn't want to ruin the illusion for the girl. It might be a weird scene, but it is also very sad. Within the casting limits of pinku films, simplicity is the key to a success. Outside of Japanese filmmakers, I also like Jeff Nicholas or Craig S. Zahler.

You have been acting since the 90s. What are the most important changes that you have witnessed, and how have you changed as an actor? Are there any directors or actors that stand out for you?

The biggest change from the 1990s in the film industry is the change of shooting devices. Until that time, it was all done on film. When the change came, filmmakers didn't need to develop the film; it became cheaper and quicker. Japan's economy was in a slump back then, so the shift was immediate. Needless to say, the production costs dropped as well. Even though it was said that pinku films had the lowest budget in the industry, in fact, they started to approach the money pool of the regular dramas or films. Since I started my career in the so-called lowest budget industry, I don't have anything against it, but for those filmmakers or actors who have no other experience than working in films that had an actual budget, it might be bewildering, right? These poor conditions have been actually a chance for me. Currently, there are no world-class stars, so there are more opportunities to work on something that will draw attention to your work. As long as it is interesting, the environment won't matter. In terms of changes to acting… there aren't any particular ones! What hasn't changed is that I still can't deliver a good performance, nor do I look well. However, I think I'm much more eager to learn about the craft than other actors in the industry. I still have much passion in me. From the excellent talent that is there in Japanese cinema, I'm really fond of Chizuru Ikewaki and Shohei Uno. No matter where they act, they have some magic in their performances. As for filmmakers, I've been always a fan of Kiyoshi Kurosawa. From those that I haven't had the chance to work with – Ryusuke Hamaguchi, Sho Miyake, and Yukiko Sode, whose “Aristocrats” have just premiered.

How do you see the new generation of directors, like Takumi Saito, Yujiro Harumoto and Genta Matsugami?

I have the impression the new generation of directors come from a completely different background than I do, and all of them somewhat surprise with their talent and vision about filmmaking. Back then, it was the principle of the assistant-director system that boosted one's path towards filmmaking, but now young filmmakers make their work among their friends or they create while doing other jobs. And they receive awards for that, too. That's how it looks now. I think the collapse of the studio system enabled new ideas, new streams of thinking. Takumi is one of those new voices on the scene. Of course, he's a very popular actor in Japan, but he's also extremely humble as a film director. I acted in his “Blank 13”, for which he invited me through social media. Up until then, it was unthinkable for me to receive a part in a film like that. As for Harumoto, I got to know him through a friend of mine and received a script for “A Balance”. What this film depicts well is the so-called correctness of media. Currently in Japan, well even across the world, there is a real struggle of oppressive mutual surveillance peculiar to the Internet society. And this is something that the media cannot really grasp, and that is pictured in Harumoto's film. This is the reason why I decided to take part in his film in the first place. As for Genta… I used to drink with him in one of Shinjuku's bars quite often. He knew that I'm an actor, but I didn't know anything about him. All of a sudden he asked me: “I'm making a film, please play in it”. I was so surprised. Only after that, I learned that he's been making music videos, etc. He's not only involved with films. His passion is also music. We got along very well, so working on “Demolition Girl” was a great time. It was a smooth project, the communication was definitely great.

In general, how do you choose the parts you want to act in?

Generally speaking, I don't choose my roles. Not only that, (I briefly explained that earlier on), I do any work no matter which genre or category of film, as long as it fits my schedule. Major films, indie films, pinku films, it's all the same for me, it's on the same horizon – this is all film. This is also my biggest flaw as an actor, but there are no roles that I really want to try. They don't exist. I entered the world of acting through an accident, even though I wanted to be involved in filmmaking. That's why I'm still an actor. I simply love movies. But, I didn't start because of my love for acting. Since there is no version of me that I want to become, it feels like freedom. It is also not about becoming famous, nor about receiving awards. But… I would be a bit happier if I could receive a bit more money for my acting. (laughs)

In “A Balance”, you play a film producer. How close to the reality of the film industry are the events that take place in the film, particularly regarding the production committees?

I'm not entirely sure about how the current situation in the Japanese TV/media world actually looks like, because I'm not inside it either, but isn't it the same in other countries as well? Each channel is different, one by one has its own pressure or bias. “Documentary” has become a very delicate and difficult world. It exists as a genre, but the real “document” is gone. That's how I see it. As long as Michael Moore edits his film in order to pursue “the truth” Michael Moore himself believes in, can we still call it a pure documentary? This becomes quite problematic. One documentary filmmaker, Tatsuya Mori, once made a film: “Fake” (2016) [in Japanese: “Documentary is telling a lie”]. This might be an extreme statement, but even if a filmmaker does not resort to lies, one still has to frame the world to make a film. And with that, once something is framed, the truth that is not inside it, the one outside of the frame, might be simply lost. Apologies, if that is not the answer you were looking for.

Are the producers usually “slaves” to the whims of the directors as Tomiyama and Yuko?

Yuko, the protagonist of “A Balance” is trying her best to get as close as possible to the notion of truth in her work as a documentary journalist. The producer, Tomiyama, to use a sports metaphor, is thinking of an immediate increase of annual winning percentage. But the thing is that sometimes you can't help but to lose. If you don't give up, the way it goes in media is that eventually, you lose the job. People above in hierarchy become accustomed to the pressure they feel. The pressure is coming from a place above them. One may ask – who is a slave to what? It is really thought-provoking. I feel how difficult it is to be persistent about the truth in this suffocating world. In Harumoto's film, I played the part of Tomiyama, who has lost his way between that pressure. And I played the part the best way I could.

Did you draw from your own experiences in the industry to portray the character?

Speaking of my experience, I think it happens every day on social media. The aspect of anonymity that enables social bullying on the internet is the horror that we're witnessing in front of our eyes every single day. It's way scarier than any film. I believe this knowledge influenced my preparation for the role. With one click, there is a possibility of killing someone. I think it's easy to sympathize with anyone all over the world if you see a picture like this.

Can you give us some details about your latest film, “Rageaholic”?

As for “Rageaholic”, we're only missing one scene. It's 99% finished. We've proceeded to CGI etc. The remaining scene was supposed to be set in New York, but due to COVID, we will have to limit ourselves to shooting only in Japan. Unfortunately. However, due to the rush of the upcoming premiere, the film became filled with quite a lot of violence and dark humour, so I'm relieved about the outcome. Yoshiki Takahashi, who's also a graphic designer, has a very clear vision of what he wants to do with his work, so it was a very pleasant and easy part. Please look forward to it!