Zhu Shengzhe was born in 1987 in Wuhan, China. She works as a filmmaker and producer in Chicago. She made her debut, “Xu jiao”, in 2014. A River Runs, Turns, Erases, Replaces is her fourth feature-length film.

Wuhan. Different Every Day.

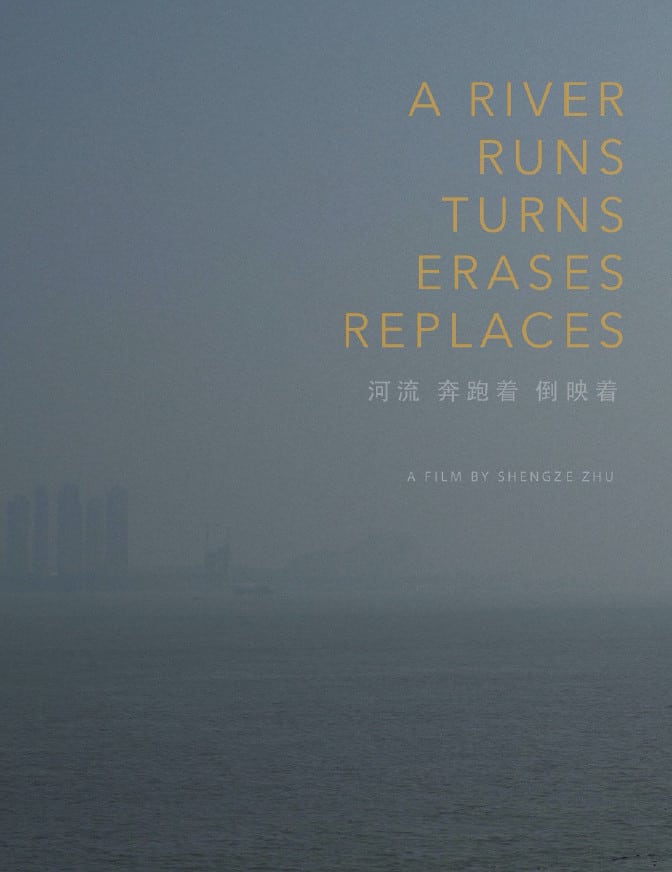

Wuhan. A city, where it all started. The current world paralysis comes from there. It's a birthplace for Zhu Shengze, an award-winning documentary filmmaker, whose recent “A River Runs, Turns, Erases, Replaces” depicts a performing backstage of the constant-changing city. Just as the stream flows further into the future, Wuhan never looks back and keeps on changing. And so are the recollections of it, they might be erased soon. This is the moment for the film to make up for the past. In an essay of snapshots of memories, Zhu disenchants a curse. This is a reconciliation, a letter to the city, a whisper to the river captured in images, in the poetry of leaving. Those, who were swept away by the industrialization, as well as the pandemics, are rendered through their final words, a narrative of fleeting that fulfills the image. It's a piece born out of helplessness and longing.

In a press note, Zhu wrote a letter.

“Initially, what drove me to make this film was a feeling of estrangement. Since I left Wuhan in 2010, I find the city has become more and more unrecognizable every time I went back home. There is always something newly built, or something in the midst of demolition. There is always the smoggy air. The city is working so hard to fulfill its official slogan “Wuhan, Different Every Day”; nonetheless, the traces of the past are almost completely erased. As a showcase of the city's forward momentum, the riverside landscape has been dramatically altered over the past several years. Buildings were torn down, roads were widened, landmarks were rebuilt. The entire area has been renovated again and again. While the city embraces the river as a catalyst for growth, what we have lost in the name of progress? How are we coping with such rapid transformation? How small and alienated one may feel in relation to the city's unprecedented scale of development? With these questions in mind, in the summer of 2016, I started to film urban spaces along the Yangtze River in my hometown Wuhan.”

I managed to have an online meeting with Zhu on the occasion of Berlinale where “A River Runs, Turns, Erases, Replaces” premiered in its FORUM section. Facing our ZOOM avatars, we discussed methodology (observing, collecting data, and selection of images and stories), the landscape of Wuhan, collective memory of its inhabitants, as well as personal reasons for making this story alive.

Amidst all the hindrance related to COVID-19, how are you?

I think I am okay. The last couple of months I felt very helpless, obviously scared and desperate at times, but now it's better. I'm also lucky compared to many other people, who had a more painful experience during the pandemic.

Your film might be a very anticipated picture of a city we all know from the headlines, Wuhan. It's a personal take – you were born and raised there. I was wondering if there was any particular moment that made you think of making the film?

I started my project in the summer of 2016. My original motivation wasn't related to the outburst of the pandemics in Wuhan. At that time, I wouldn't think of my hometown becoming infamous for such a frightening reason. In the past, when I told people that I was making a film about the landscape in Wuhan, nobody even knew about the city. Even now, people rarely have a solid understanding of the city. Everybody has heard of it, but it happened due to the context of the COVID-19 pandemics. My original plan was to finish shooting last year, as I thought that five years would be a good lens for grasping the evolution of the landscape. It wouldn't be too short, nor too long. But I couldn't go back to Wuhan due to travel restrictions and quarantines, so eventually, I wasn't able to continue working on the project the way I planned. In the meantime, I felt that I really needed to finish it. For other reasons than the pandemics – first and foremost – it felt like self-treatment. I needed to make it and it meant a lot to me on a personal ground. It became a very personal film, indeed. It was until January 2020, that nobody has ever heard of the name of the city, so I also hoped that my film could add some things to these pre-existing discussions or coverage of the city.

Do you think you found consolation after finishing the film?

Maybe consolation is not the right word. Because of what happened, I thought I had so many things that I wanted to say, but I didn't know how to do it. I didn't know if I want to attack someone or put in verbal language, because I thought it might have been too intangible or too complicated. Since I'm a filmmaker, I could only make a film out of it.

Since you worked based on your memories of the city, how did you approach the selection of the images of Wuhan?

Most of the images are from the area close to the river, Yangtze. This is the place I'm very attached to because I grew up there. The riverside has recently become a showcase for the city's rapid development. In the beginning, I knew I wanted to focus on this area, both for a personal and industrial reason. The film was about showing what we have lost in the name of progress. I picked them by using the map on my phone, and since the area is really enormous, I realized there are many places that I was not familiar with. I started to become more interested in those places that are about to go away or change. My focus switched to the transient nature of space. I had a feeling when I was standing there, by the riverside, in front of huge concrete and steel buildings, that I am so tiny. These buildings seemed so powerful like they could outlast everything. One week later, I revisited these places and they might be completely gone, vanished. I couldn't recognize any of it.

Wuhan is full of contradictions – there are huge buildings that overshadow your sight, but the next day you realize it's a transient world, and that it's gone, that these buildings were destroyed in a week. I wanted to translate that feeling, define my perception of that space, and then transform it into a film. I'm also interested in those mundane little details, nuances, subtlety – how people find their everyday life among that huge landscape, how their routines look like. In my previous films, for instance in “Another Year” I worked on a very intimate relationship. I spent a year with a family, closely observing them and following their life. After that, I thought of how I can be close to someone, but without getting close or knowing personal details. That's why this time the camera is further away from the people. I turned in to exploring the relationship between humans and the landscape. We invade space, although the riverside is supposed to be on its own, sculpted by nature, not by machines. After all, we see a river that is surrounded by dams or bridges and I wanted to examine this relationship.

In your previous film, it was the private realm that dominated your gaze. In “A River Runs, Turns, Erases, Replaces”, you focus on the public. What was the biggest challenge in that transition?

I think it turned out quite naturally. The majority of the space along the riverside is a public space, as it belongs to the state. There are parks or construction sites, so maybe it's not entirely public, but neither it is private, right? From the beginning, I didn't intend to focus on any specific group or individuals, but rather on the space. For me, the space around the Yangtze in Wuhan is a stage. There are all different sorts of performers on it: residents, tourists, old and young, and everybody comes from a different background. On top of that, you can notice machines, bridges, the infrastructure of the city that was built by human beings. And then, there's nature. The wind, the water, the trees, and gravity, not everything visible, but it is there. Finally, there's one key character, an invisible one, which is the authority, the Chinese state.

With my film, I tried to recreate the dynamics of this stage in a public space. I believe that at some point it became my biggest motivation. After observing Wuhan for some time, I realized that it's not about the public and the private, but rather about collectivism. What we look at, what we observe, and what is our point of view – it all comes to the collective memory. Someone's perception of the river will differ from my understanding of this space, but since the river serves as a symbol of the city, it is inherited as an integral part of the memory of all the inhabitants of Wuhan. Space became a collective character of the film. If you take a look at what we experienced in the last year – with the pandemics, the lockdown – we're all living through it together, and that's the collective memory, with individuals having a piece of their own story. That's why for me it became the public and the collectivism.

Between the images, you also implement personal stories from the individuals. They serve as letters to the ones who are gone because of the pandemics. How did you encounter these stories?

When I started shooting the film, I knew that I can't ignore what happened throughout the last year, but I didn't have footage from the time of pandemics. Through these stories, I managed to make a connection between the last year and the further past. I thought of using the text, like a combination of tweets or Weibo posts from different individuals, but it didn't work out. The connection wasn't enough. Then I found out about people who wrote their diaries on the internet. There was a website, like a map, where people posted their intimate stories about losing someone. They addressed their messages directly to someone they lost. This guided me to my friends. I started talking with those who are close to me, their families, their friends.

What happened with the pandemics was unexpected. Nobody was prepared for it. When they were facing this loss, they had so many things they wanted to say, but they couldn't find a place to do it. They didn't know how to coin their grief. The letters in my film are based on the feelings of those who lost their families last year. I sometimes quoted them, because we talked a lot, but mostly, I was writing my perception of it. These intimate stories became my voice of the story of loss. They're all my letters.

You mentioned that the riverside became a stage for you. The visual language of the city, with its neon, lights, and visual performances, seemed to be an important aspect of the city's development. The motto of the city is: “Wuhan. Different Everyday”.

As I mentioned, the riverside became the showcase for the city's development. The government tries hard to build the image of the city through what's visual: light shows, ambitious projects, or many other things. The lights I show in my film are projected on thousands of building synced together. Of course, it's very interesting to look at it, but it seems to me that there is no narrative or structure. The government tries to sell the image of a city that is different from any other city in any other country, that's the only narrative there. Projecting such lighting on the buildings is impressive, but it takes so much power and effort. You need to have things under control to maintain this, so it becomes a showcase of power and development.

Since your films are a representation of observational documentaries, I was wondering if you noticed to have observed yourself?

It's always a chemical reaction between me and what is happening in front of the camera. I think that observing others helps me to reflect upon myself or my thoughts, or the way I think. I'm also trying not to put boundaries between what is documentary and what is fiction. It's always an attempt of blending my perspective with reality, the real people around me, and all the events that happen to them. Then I reconstruct or deconstruct the representation of that reality through my perspective. There is always this part of me that I try to observe through my films, but I think “A River Runs, Turns, Erases, Replaces” was different. With my previous projects, I could just leave my objects after I finished filming them. Their lives and my life were two parallel, separate lines. It also made me feel like an outsider. With this film, it felt that I'm more like an insider this time. There was no exit door for me, I couldn't just leave the city no matter how far I went. But to answer your question, I'm trying to observe myself. It's very difficult though, not only for a filmmaker but also for a human being – to be close to yourself. That's a very difficult thing.

Your film reminded me of one that was banned in China for the critique of industrial imperialism, “Behemoth” by Zhao Liang. Do you think that the Chinese audience will have a chance to watch your film?

I really don't know. They can always find a way to see my film if they want. There's always a way.