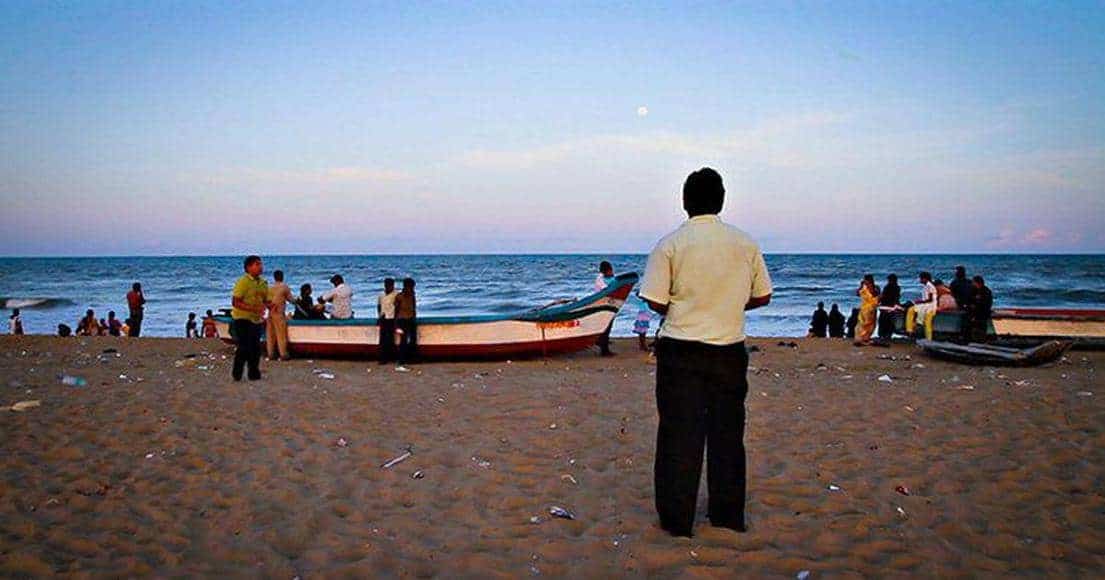

“Lost Course” won Best Documentary at the Golden Horse Film Festival 2020, and several prizes at the recent Taiwan International Documentary Film Festival 2021. It centres on Wukan, a fishing village in the Guangdong province of Southern China, which attracted international media coverage in 2011 as the site of anti-corruption protests by the villagers. “Lost Course” tells the story of the village's struggle against corruption over the course of five years, following the lives of several of the villagers involved in the protests and the subsequent elections. The original unrest was sparked by revelations that local farming land had been sold to developers without the villagers' knowledge, and without them seeing any of the proceeds.

Lost Course is streaming on OVID.tv

The film is divided into two parts: The first covers the protests, subsequent détente and election of a village committee, ending with a sense of optimism about the village's future; the second deals with the situation in the following years, where the hopes for an improvement in the village's fortunes sadly do not materialise.

Li films and directs a documentary in the observational style; there is no narration and any prompting of the subjects is virtually imperceptible. An area where “Lost Course” really excels is the way it follows the lives of several of the key villagers over the course of the film's timespan: from the disputes, through to the establishment of Wukan's fledgling democracy and beyond. As well as documenting their roles in the evolving situation in the village itself, we get to know some of the characters more personally, which adds a nice counterpoint to the political machinations which are the focus of the film.

The camerawork is a little raw in places, no doubt due to the conditions under which some of the filming takes place, but if anything, it enhances the candid feel of the production. ”Lost Course” must have been edited down from hundreds of hours of footage and it is no mean feat that what results from Luke To, Jill Li and Lau Sze Wai's cutting is an incredibly coherent movie.

Whilst I baulked slightly at the prospect of watching 2 hours 59 minutes of documentary, I was pleasantly surprised at just how compelling “Lost Course” is. In recording the developments in Wukan, it paints an almost fatalistic picture of how the initial optimism for change gives way to the very same corruption which began the chain of events which it documents.

But it also offers a much more complex picture than simply a cynical portrayal of corruption. It shows the more personal sides to the main protagonists and articulates complexities such as the relationship between the village committee, the regional government, and the Party. Ultimately, it conveys that what is promised by politicians is so often difficult to deliver due to a myriad of factors and leaves one with the impression that, corruption notwithstanding, it would have been difficult getting what the villagers were agitating for, whoever was at the helm.

“Lost Course” also provides valuable anthropological insights to those not familiar with modern China, and those interested in politics – Wukan's election was the first in China to use a secret ballot and was reported by international journalists as being impartial, something that cannot always said of such elections.

Compelling, and multifarious in its aspects, “Lost Course” is a tour de force of observational cinema.