Many of the books on Asian cinema I have read and reviewed feature impressive research, thorough analysis, and intelligent, accurate comments. This is the first one, however, that the part of the (cinema) history it focuses on, and the way Lee Sang-joon has written about it, could easily provide the script for a captivating, “true story” movie. Particularly the way a decision from US Intelligence to counter communism through cinema eventually led to Run Run Shaw becoming a Pan-Asian film mogul, and Shin Sang-ok the maharajah of Korean cinema, is a truly wondrous part of history, that finally gets told in all its glory. Since I am oversimplifying, however, let us take things from the beginning.

Buy This Title

As mentioned in the author's introduction, “This book is a history of postwar Asian cinema (…) the first book-length examination of the historical, social, cultural, and intellectual constitution of the first postwar pan-Asian cinema network during the two decades after the Korean War Armistice in July 1953. (…) US agencies-the Asia Foundation (TAF) in particular-actively intervened in every sector of Asia's film cultures and industries during the 50s.”

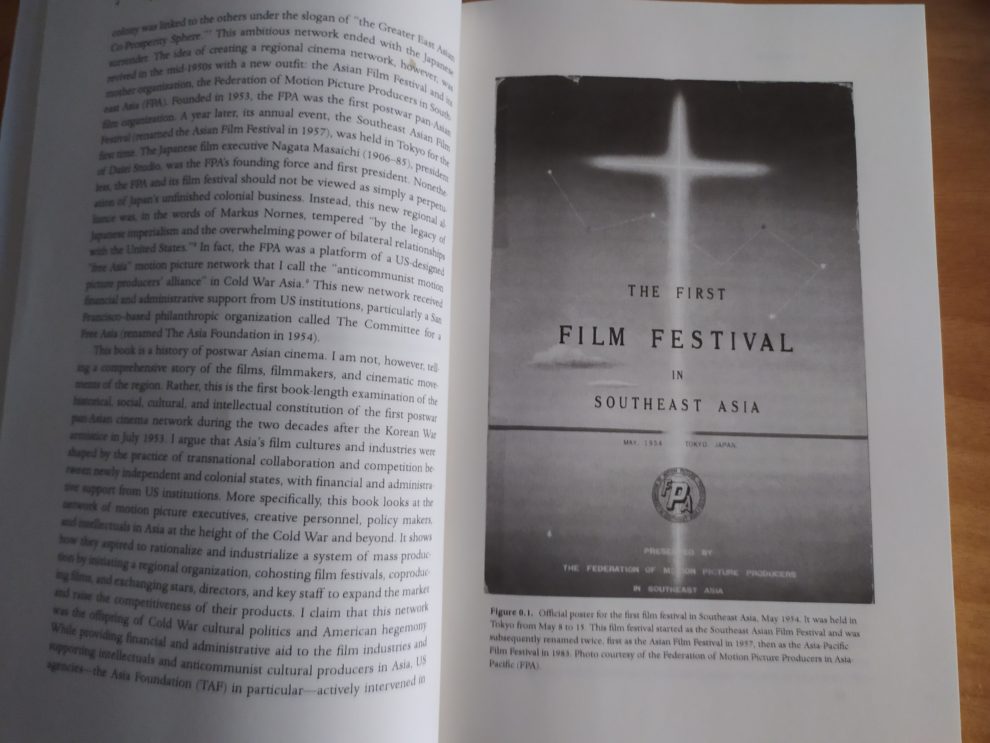

In that regard, the story begins in 1953 with Charles M. Tanner, the Hollywood liaison of TAF, who was looking for ways to influence the Asian film market, through the Southeast Asian Film Festival, which was the annual event of the Federation of Motion Pictures Producers in Southeast Asia (FPA). The FPA was established by Japanese film executive Nagata Masaichi, president of Daiei Studio. With the help of TAF, which was later on revealed as an organization subsidized by the CIA, other organizations like CFA and Radio Free Asia, and a number of either willing or coerced Hollywood vanguard talents of the likes of Capra and DeMille, the project to “infiltrate” and essentially take charge of FPA, begun.

The role figures like Run Run Shaw, Nagata, Manuel de Leon (Philippines), Djamaludin Malik (Indonesia) played in the shaping of the FPA and the first deliberations regarding the “rules” of the Southeast Asian Film Festival, are examined thoroughly next, with the book exemplifying the fact that history revolves around specific individuals.

The way psychological warfare, US anti-communist propaganda and Cold War politics shaped the field in Asia in the next years, and the way Run Run Shaw exploited the whole concept in order to establish his empire are also presented in the pages of the book. The part US film festivals, and particularly the San Francisco International played in introducing Asian films to the US is analyzed next, as the stories of individuals and events become more and interesting, also due to their intermingling, with the way Shaw Brothers and Shin Productions cooperated providing one of the most interesting chapters of the book. In general, the story of Shin Sang-ok and his wife's Choi Eun-hee, from becoming Korean film moguls, to being abducted by North Koreans to shoot movies there, and their escape to the US where they also produced movies, emerges as another rather interesting chapter.

The rise of the kung fu movie and the role Korean “imports”, mainly directors and actors Shaw Bros brought in to work in Hong Kong is also analyzed here, while chapters about the Hawaii International Film Festival and the transformation of the Asia Film Festival to Asia Pacific Film Festival, with the entry of Australia in the Association, close the history of the tome.

The level of research Lee Sang-joon has conducted here is impressive, since not only all the events are analyzed fully (and for the first time) but almost every individual mentioned here also gets a mini biography, particularly regarding his involvement in the particular history, but frequently even more. The succession of events is ideal in order to paint the story as thoroughly as possible, while highlighting the context that led to the specific events, and particularly the powers within, which were the ones that actually shaped the whole cinematic setting in Asia, at least until the end of the Cold War.

The main comment is rather clear, starting with the fact that the FPA was essentially the de facto Cold War film network in Asia. Money and politics, and certainly not art, was what shaped the Asian film industries at the time, with the efforts of all the big companies to implement Fordism, the assembly line style of production that would allow them to come up with as many movies as possible with the lowest cost, being repeatedly highlighted in the book.

The overall language Lee Sang-joon uses is simple, to the point, mostly consisting of relatively short sentences, which is essentially ideal to present the complexity of the history analyzed here, resulting in a rather easy to read book. The placement of the notes in the back detracts a bit from this trait, but not to a point to harm the reading of the book significantly, while the catalogue of abbreviations in the beginning eventually emerges as one of the most important parts of the book, particularly for the first, introductory chapters. The Korean names follow the McCune-Reischauer form, which I feel is not the one that has become the norm, for example Ch'oe Ǔn-hŭi instead of Choi Eun-hee, although again, this is more of a detail than an actual issue.

I would not like to get into comparisons about the quality of the books regarding Asian cinema, but the fact remains that “Cinema and Cultural World” is definitely one of the most entertaining, as the story presented here could easily be the basis of a novel (or a script as already mentioned), to the point that I feel it would provide a rather captivating read even to readers who are not particularly interested in film history.