A home isn't just four walls and a roof, but a building that has with it many years' worth of memories for its inhabitants. And for some of the elderly, the home isn't just where they live, but their life itself. This is the theme of first-time director Yoshihiko Ueda's loosely-plotted “A Garden of Camelias”.

“A Garden of Camellias” is screening at Toronto Japanese Film Festival

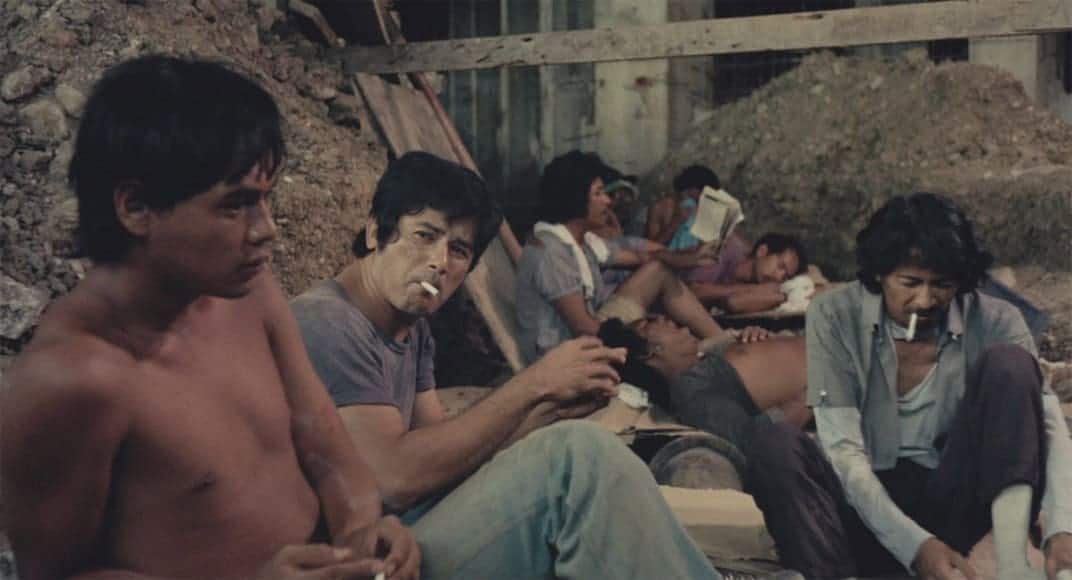

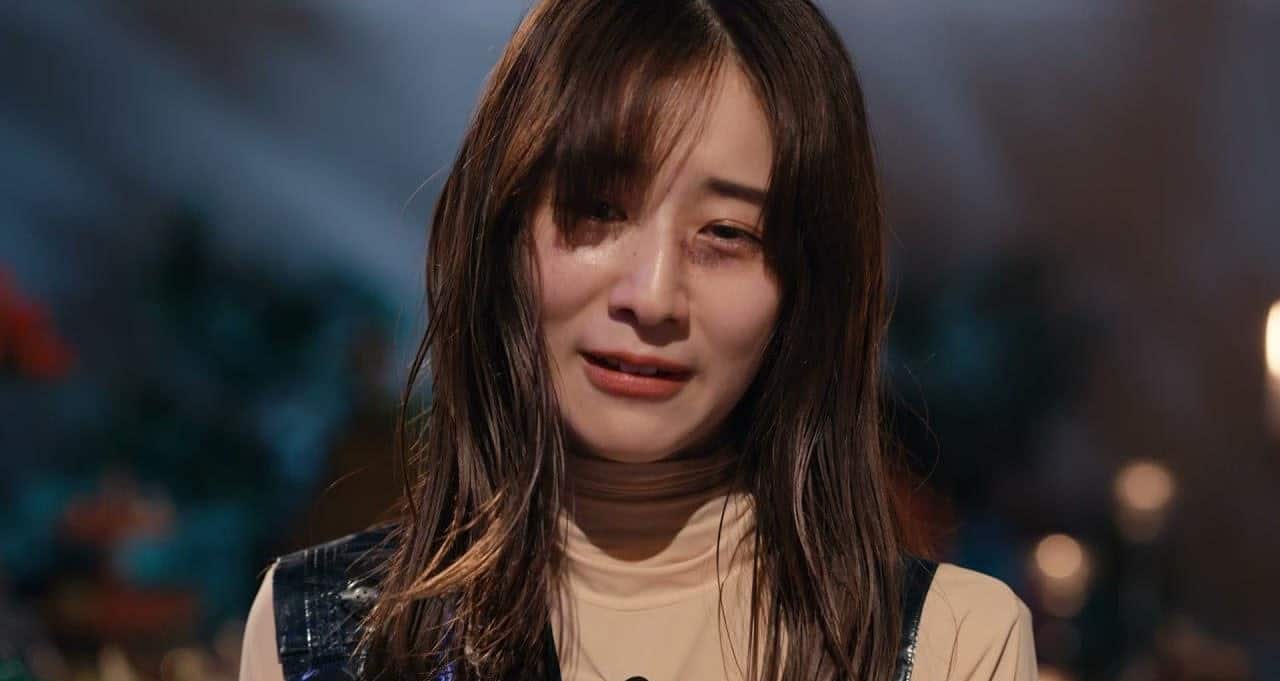

Kinuko (Sumiko Fuji) is recently widowed and taking guests as part of the important forty-ninth day memorial for her late husband. Since the death of her estranged daughter, her granddaughter Nagisa (Korean actress Shim Eun-kyung) has lived with her as she tries to acclimatise herself to Japanese language and culture after her mother left the country. Kinuko now spends her days tending to her generous garden of natural beauty and helping Nagisa with her Japanese. But with problems regarding inheritance tax on the horizon, Huang (Taiwanese legend of Wong Kar-wai films Chang Chen), her tax accountant, makes it known that she will have to sell the property as she will not be able to afford to keep it on. Her other daughter, Toko (Kyoka Suzuki), offers for her to move in with her family, while she reluctantly allows Tokura (Seiichi Tanabe) to draw-up plans for the building's future.

Ueda doesn't give much away to start, and with its slow pace and long run time, you have to learn what is going on as the film progresses. Initially, the viewer will feel as if they are watching a nature documentary, with close-up shots seemingly devoid of context and intense sound engineering. For photographer Ueda the garden – and indeed house – are the main characters. Dialogue, storyline and action are largely absent, with the piece serving largely as an aesthetic portrait of a Japanese garden in a Meiji Restoration period house.

The fact that it is a Meiji Restoration era house is significant: On the forty-ninth day memorial, Kinuko and Nagisa find a dead goldfish in the garden's pond. This death signifies a greater end. A traditional Japanese house, but with Western touches throughout, by the conclusion we learn that Tokura has different intentions for the property than Huang promotes. The final shots are a brutal end to what is a slow, lingering homage to the garden's natural beauty.

Ueda chooses a pace to match the association with a Japanese garden: A place to sit and ponder on life. This essentially means that we see little in terms of action and story. When in the garden, we are treated to shots of vibrant colours and insects going about their work. The interior shots of the house, however, are a stark comparison of mournful silhouettes.

And mournful is the key word for this film. Not only does its pace linger in sorrow, but what little plot there is focuses on death. Kinuko's husband's death is our starting point and her daughter's death is referred to throughout; while the goldfish discovery at the beginning shows the start of the garden's decline. But death is more of a cultural concept that Ueda wants to communicate, as the conclusion makes obvious: A traditional building and garden developed over many years, creating countless memories, are to be destroyed in an instant.

Ueda has to walk a difficult balance between the slow pace and the fact things could have been heavily edited. The slow pacing feels necessary in building the aesthetic qualities of natural beauty and reflections of the past, which would be lost if cut back. But having said that, does it require its extended runtime? We are left with the relaxing feel of having sat in a garden, reflecting on life, which works if you allow this to happen. But the more impatient among us maybe left craving for something more. It is not until the closing scenes that we leave the grounds of the house, and then only briefly.

Like Jun Ichikawa's “Tokyo Marigold” before it, “A Garden of Camelias” uses flowers as a metaphor for change and how all things will come to an end. Ueda wants us to have the patience to grow with the work, not trimming things down. Modern society may not have the time for this, but real beauty takes time.