Languages spoken by the indigenous people get extinguished through the dominance of the official onesm either by the deliberate neglect of official governments, or through planned actions, bans and direct oppression, but also very often through migration. When languages start disappearing, traditions and customs follow to slowly fade away. This is a story as global as any other that stands witness to the identity-robbing process of assimilation, painfully universal.

Ainu Neno An Ainu is screening at Nippon Connection

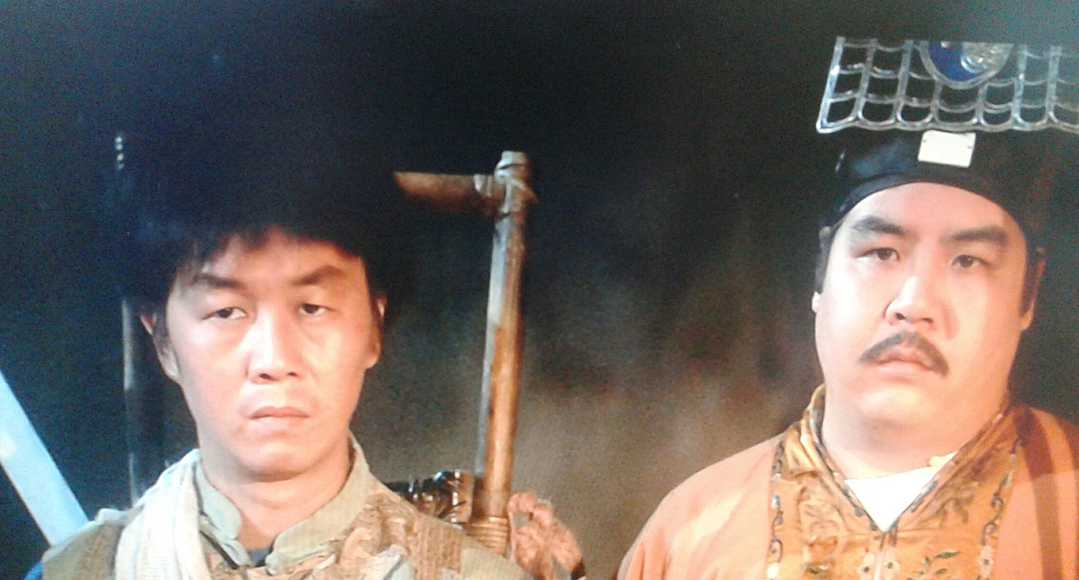

Ainu culture was endangered long time ago through the decision of the Japanese Meiji era Government (1868-1912) to develop Hokkaido, which is when the Ainu land was confiscated and their language banned. This is just one of many details learned through a voice-over by a college student Maya, a native Ainu who grew up in the village of Nibutani in the Hokkaido prefecture. Almost as if thinking aloud, the girl accompanies the documentary “Ainu Neno An Ainu” directed by the Lunch Bee House collective comprising of Laura Viverani, Neo Sora & Valy Thorsteinsdottir.

Lunch Bee House members like to call themselves “a punk band of documentary filmmaking”, but there is no anarchy in their warm portrait of a small, tight-knit community with many interesting stories to tell. The collective was formed for the purpose of bringing out the story of this fascinating culture, and according to the press release, its name is “an homage to an Ainu restaurant in Nibutani run by Yukiko Kaizawa, one of the film's protagonists.

“Ainu Neno An Ainu” is built as a digital album of many village inhabitants presented in their natural environment – which isn't always (nor necessarily) a lush greenery surrounded by mountains, although we observe some of them in their nature-bound activities such as planting trees or working in the field. The others simply do what they usually do, even if it means pulling off a show that is from time to time served to tourists welcomed by a man dressed in a superhero costume as “Biratoranger #3, the protector of Birangi”.

The film project had started out of curiosity, without any previous connection with the protagonists of the film. Nibutani was a logical choice for exploring the Ainu, being very well known in Japan for its indigenous cultural heritage.

Initially, it's Maya who starts introducing the others to the camera, but after a while they simply take over telling their own stories about the search for identity and the efforts to preserve what's left of the Ainu traditions. Some are dedicated to the traditional crafts such as attus weaving, carving and embroidery, the others are trying to re-learn the language of their ancestors. There is an opportunity to see three different generations making an effort to pick up on the language they have forgotten or never had the opportunity to learn. For those with a bit of knowledge, Ainu lessons on STV radio are quite useful or the youth visiting the courses teaching them vocabulary and grammar. They have to pick it up acoustically since the language never had its written form; it was passed on from generation to generation orally.

The film is done with heart, and the established closeness between the filmmakers and their subjects is pulpable.