It is one of the main ingredients of a good effect that the viewer does not notice it. Perhaps it is difficult to fathom it, but even in the era of the blockbuster and big tentpole productions, any kind of effect should first and foremost serve the story and not the person responsible, which may be one of the key reasons why so many artists, sound designers, cinematographers, editors and make-up artists are not that recognized, although their craft is enjoyed by millions of viewers. While the visuals are of course significant, sound plays a vital role in the enjoyment of a movie and the experience of being drawn into the world and its characters. With the advent of digital effects, the availability of sounds from all over the world is quite breathtaking and utilized by many productions, while at the same time, this progress makes the job of someone like a foley artist somewhat redundant.

Foley Artist is screening at Taiwan International Film Festival Berlin

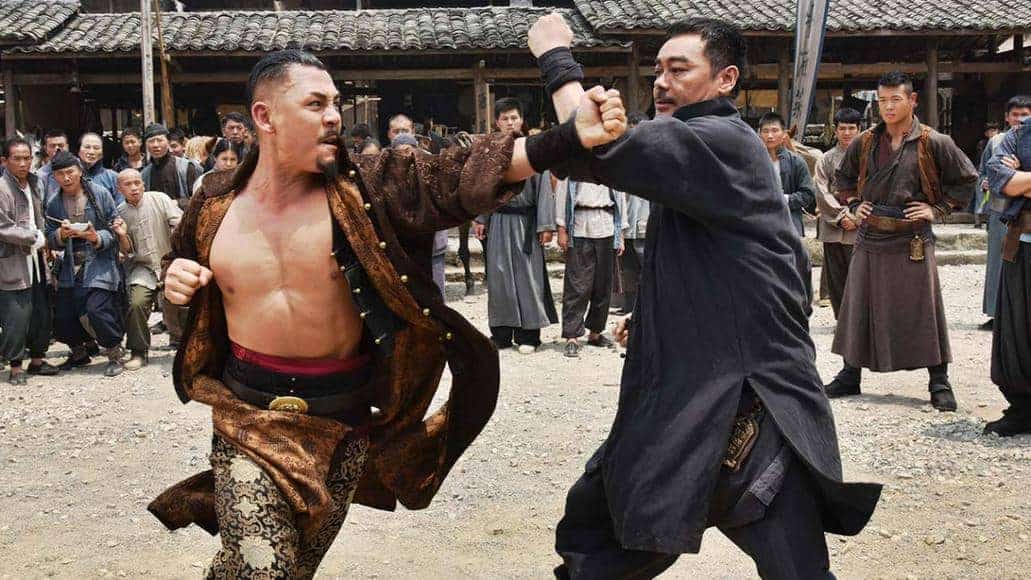

In her documentary “Foley Artist” director Wang Wan-jo introduces her audience to Hu Ding-yi, whose work has been enjoyed by many Taiwanese viewers for quite some time. Hu has been a foley artist for 40 years, creating sounds effects for countless Chinese-language movies, from footsteps in the rain to breaking glass and kids playing ball in the background of a scene. His methods may strike one as quite unorthodox at first, but after a few minutes witnessing him creating various sounds for the meeting of a boy and a girl in a movie, you cannot help but marvel at the craftsmanship and creativity of this man. Through interviews with him and his apprentice, Wang explores the studio of the foley artist, who always searches for new way to create sounds, for example, by going to flea markets, looking for gadgets or tools. Wang is a many driven by creativity, more so than getting the job done, and takes quite some pride in what he does.

Besides presenting Hu's work and his philosophy, “Foley Artist” also aims to explore the Taiwanese film industry and its history. Wang also interviews filmmakers, editors and composers to show the versatility of Taiwanese cinema, as well as the amount of work people like Hu have invested to dub and score foreign movies for home audiences. Apart from the country's history, the interviews and the archival footage Wang uses in her documentary emphasize the technological advances in the various fields of post-production. In essence, we witness how jobs like sound design, especially the way Hu has done it for so many years, has become a lost art, one which is still admired by many of his peers, but which is nevertheless endangered.

While the amount of information, which comes naturally with a project of this scale, is quite enormous, and it might be tough to take it all in upon first viewing, what shines through is how “Foley Artist” tells a story about enthusiasts. Hu Ding-yi is likable and knowledgeable, but above all one who is passionate about movies, and thus doing the best he can to enhance the audience's experience.

In conclusion, “Foley Artist” is a great documentary about the lost art of sound design, as it was done before the digital age. While Wang Wan-jo looks at the past and what will be lost when Hu Ding-yi has finished his last movie, she also manages to tell a story about people who feel passionate about the medium and dedicated towards what the audience experiences when the lights in the cinema go out and the movie begins.