Unlike any other genre, horror offers perhaps one of the most unique keys to the human psyche, especially human fears. Leading back to Romanticist poets and authors, the disruption of the human sphere and the supernatural has always proven to be a link to social phobias and trauma. Logically, horror does not need to follow the rules based on reality, which is interestingly – and somewhat ironically – an aspect readers and audiences sometimes expect the genre to do. Living through the notions of the narrative with the obligatory “I would never go there.” or “Don't go into the basement.” is part of the excitement, but also the various criticisms of how a story could never happen like this.

Watch This Title

However, this is not what horror is supposed to. According to Japanese screenwriter Konaka Chiaki, who wrote the script for Takashi Shimizu's “Marebito” (2004), real-life terror does not follow any sensible rules, and neither should horror. “Terror is absurd” he states, and most horror narratives do not follow the principle of causality or over-explaining their characters or their plot. Perhaps this is the reason so many Japanese horror directors refer to the cinema of directors such as Mario Bava and others, since their work rarely offers explanations rooted in reality.

For reasons such as this, directors like Kiyoshi Kurosawa remain among the most interesting working in film, in particular the horror genre. With a major in sociology from Rikkyo University, Tokyo, Kurosawa has put what he has learned into practice ever since his first features from the 1970s. In the 1990s, Kurosawa was finally revealed to Western audiences as a director responsible for some of the most significant entries in the field of J-horror, namely “Cure” (1997) and “Pulse” (2001).

“The Guard from Underground” already shows significant steps in the direction Kurosawa would go with the aforementioned features. Albeit having studied sociology, he clarifies how his scripts and the visuals of his films derive from other titles he has watched over the years. Nevertheless, they are far from being mere exercises in intertextuality, since narrative and characters will have to prove themselves against the backdrop of his own experience. As a conclusion, Kurosawa sums up how true horror has nothing to do with change or the supernatural, but in the modern world, derives from not changing at all.

Akiko (Makiko Kuno) begins working in Department 12, an office responsible for acquiring and selling pieces of art internationally. At the same time a new security guard, Fujimaru (Yutaka Matsushige) also has his first day on the job, but quickly arouses suspicions with his superiors because of his strange behavior. When he sees a photo of Akiko, he becomes obsessed with her, starting to stalk and even trap her temporarily, within a storage room.

Even though Akiko and other colleagues are afraid of the tall, new guard, neither Kurume (Ren Ohsugi), head of Department 12, nor Hyodo (Hatsunori Hasegawa) see any reason to act. As Fujimura's obsession increases, he finally decides to take more drastic and violent actions to reach his goal, but also against all those standing in his way.

In one of the first interviews the homepage of Midnight Eye conducted, Kurosawa offered further insight into his approach of making movies. Apart from the aforementioned aspects, film has to be a medium recording the world around you as well as the kind of values an individual embraces. The way these values oppress and define a character has been one of the foundations of his approach to film from the start.

Considering “The Guard from Underground”, this approach already shows itself in the first minutes Akiko sets foot into the offices of Department 12. Although dealing with items of beauty highlighting individuality, these issues have become lost in the competition with others, reducing the way art is seen to mere monetary value. The characters, however, have applied this formula to the individual as a whole with one of her colleagues, Yoshioka (Taro Suwa), comparing art's change of worth to a woman's changing beauty. Perhaps the best example is Hyodo, boss of Human Resources, who cynically evaluates employees as “trash” and without any lasting worth to the company.

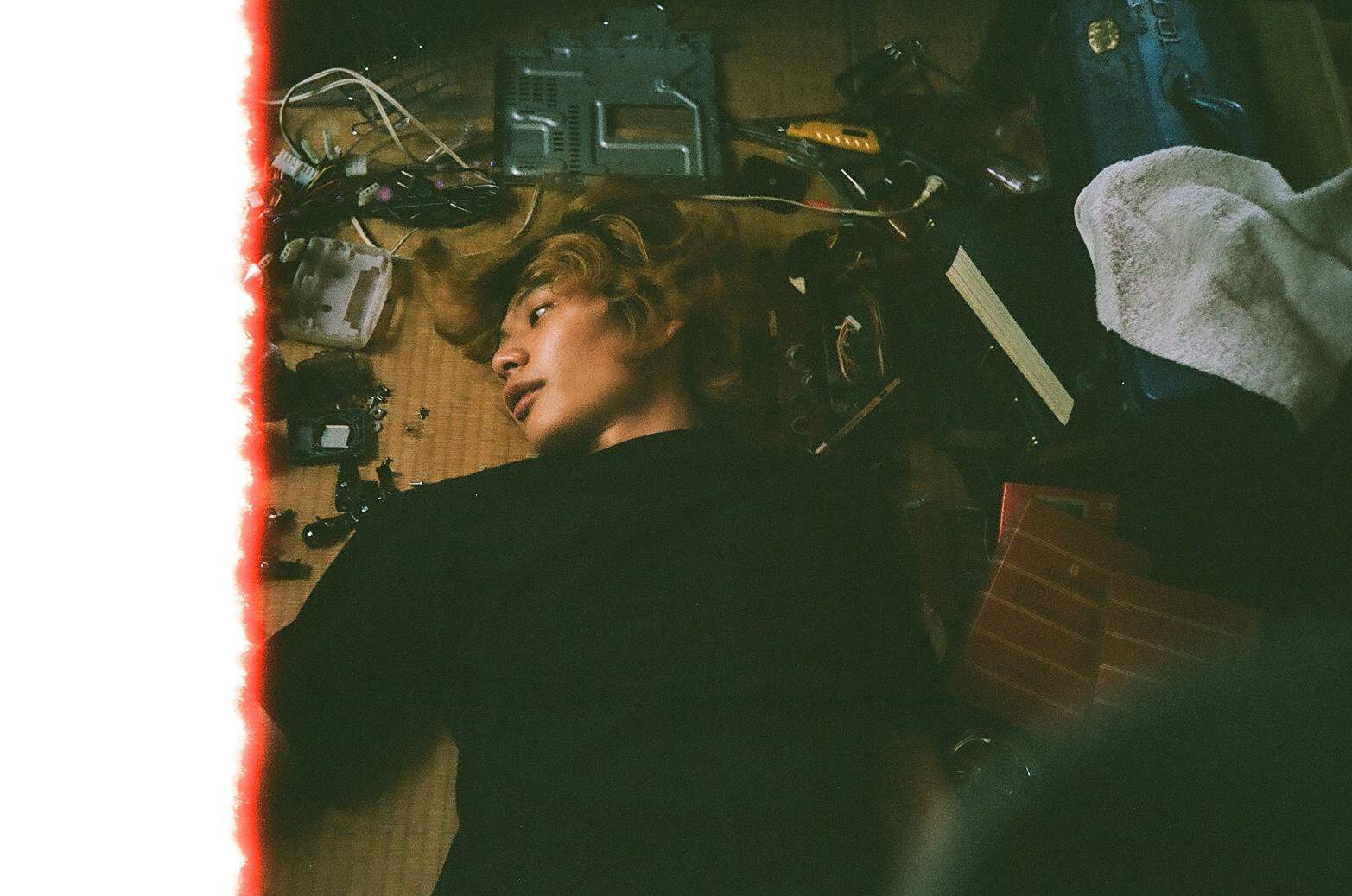

Aesthetically, “The Guard from Underground” already showcases some of the aspects which will define Kurosawa's cinema, especially the entries within the field of horror. The action is limited to the office building with varying uses of lighting, from unnaturally bright areas like the offices of Department 12 to the murky rooms of the guards. With the absence or presence of light, the influence of the supernatural, the evil entity, in this case Fujimura is emphasized, a character whose actions slowly transform the surroundings into a hellish place.

Additionally, Kenichi Negishi's supports the slow transformation of the artificial office environment into the killing ground of the guard. Sparse use of close-ups combined with medium shots, underlines the characters as products of this place, providing a feeling of growing terror and despair, of being trapped. Ironically, even before this transformation, Kurosawa's film shows very little of the outside world, most of it observed through an office window or from an elevated view making people look like insects.

Lastly, the music composed by Yuichi Kishino and Midori Okamura provides a nice dreamlike canvas for the film. Especially within the in-medias-res opening, the use of music adds a surreal tone to the atmosphere of Kurosawa's film.

“The Guard from Underground” is a film which shows many of the later trademarks of Kiyoshi Kurosawa's brand of horror. Great cinematography, magnificent music and lighting will likely find admirers among those fond of J-horror and atmospheric films in general. Of course, in comparison to later works, this one has many flaws, missed opportunities, especially since its last half is too much embedded within the conventions of slasher. However, it holds more than just a promise, and within Kurosawa's body of work it is a small, but significant piece of work.

Sources:

1) D., Spence (2011) Interview with Director Kiyoshi Kurosawa

http://www.ign.com/articles/2001/08/23/interview-with-director-kiyoshi-kurosawa, last accessed on: 06/16/2018

2) Choi, Jinhee; Wada-Marciano, Mitsuyo (2009) Horror to the Extreme. Changing Boundaries in Asian Cinema. Hong Kong University Press

3) Mes. Tom (2001) Interview with Kiyoshi Kurosawa

http://www.midnighteye.com/interviews/kiyoshi-kurosawa/, last accessed on: 06/16/2018