Written by Masao Adachi, one of director Koji Wakamatsu's most important collaborators, shot in 4 days in the same building that used to house Wakamatsu's film company and cheekily conveyed via a flimsy pinku veneer, “Go Go Second Time Virgin” is one of the strongest portraits of 1960s' nihilism and a powerful poetic statement about a generation miserably failed by society.

Without much warning for the audience, before the opening credits, a girl called Poppo (Mimi Kozakura) is gang-raped by a group of young solvent-sniffing losers on a rooftop terrace. It's night, the girl screams at first but after a bit she succumbs to the inevitable, becoming completely non-reactive. On a side, another teenager is looking at the scene; Tsukio (Michio Akiyama) is not part of the gang, he is just an observer, but he doesn't do anything to stop them while a mix of arousal and existential boredom crosses his face. Left naked and bleeding, Poppo remains the whole night laying still on the terrace, only to find out in the morning that her observer is also still there with her. Poppo begs him to kill her after revealing – in a blue-tinted flashback on a beach – that this is the second time she is raped. Gradually the two start to talk and connect; they share a past of violent abuses and a hopeless future. Tsukio too has been sexually molested by four adults and he coldly shows Poppo the murderous consequences of that episode. He grabs the girl and takes her into the building to his flat first, where a bloody crime scene is paraded in the living room, and then to the basement, to a big pile of rejected poetry books he wrote. Back to the rooftop, another night is coming, and the gang of rapists is back. Problem is, the caretaker has locked the door and they are all trapped on the roof until morning. Violence explodes with tragic and inevitable effects.

Absurd, extreme and relentlessly depressing, “Go Go Second Time Virgin” is a desperate symbolic representation of a generation trapped by a negligent society that is not able to look after it or nurture it. Here, like in many Wakamatsu's films, the social malaise interweaves with sexual violence. In a significant yet brief scene, Poppo's violated body lays on the concrete, while a middle-class housewife suddenly appears, totally unaware, and happily hangs the washing in the sun. She supposedly represents the family and the community that ignored and failed our protagonists.

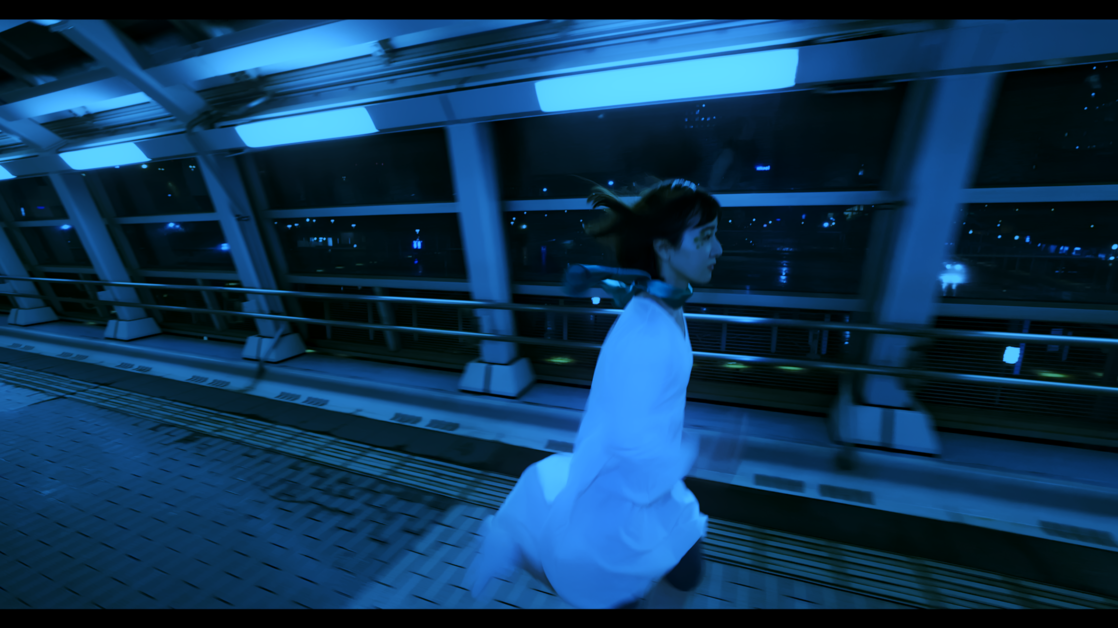

The location is a central and prominent element of “Go Go Second Time Virgin”. An opportunistic choice for this next-to-nothing-budget project, the terrace is the roof level of the block where the office of the Wakamatsu Pro was situated, but despite the easy go-to choice, it proved to be an atmospheric and oddly claustrophobic stage for the two tragic heroes and a strong metaphor of the society that has imprisoned and cut-off the two teenagers. Like a cursed cruise ship, sliding slowly on the indifferent city above, surrounded by jail-like high metal railing, exposed to rain and sun, the terrace is a bubble, a microcosm raged by violence, rape and suicide. Equally impressive is the excursion into the labyrinthine gutters of the building. The handheld camera frantically spirals down the flights of stairs to reveal the full lurid colours of murder and down again to the sad mountain of rejected poems, a testament to Tsukio's alienation.

Despite the pinku-eiga-style title, and the nudity on display, the sex in “Go Go Second Time Virgin” is far from titillating. Instead, it's a sordid and animalistic affair; the masculine bodies rub against Poppo's naked flash, groping and fondling while the girl zones out, into the comforting void created inside her mind. Hardly exciting, but prolific and radical director Koji Wakamatsu managed to exploit the possibilities that independent pink cinema could offer in full; total freedom to make films of political defiance with deep artistic and existential connotations, in exchange for few inches of bare skin.

Shot in a contrasted black and white, the film has moments of colour, like a blue flashback and an oversaturated murder scene. The rather interesting soundtrack is a bizarre mix of free jazz pieces and American experimental music of the time; at several points, Tsukio sings a melancholic ballade (written by Michio Akiyama himself) where he refers to Norman Mailer and his desertion of the Vietnam War and other poetic allusions. As the climax descends to the finale, violent sequences of manga (Lone Wolf and Cub) flash in front of the audience together with photos of pregnant Polanski's wife Sharon Tate (the infamous murder had just happened when the film was made).

Just before the final act, the two protagonists look like they have regressed to a state of happy childhood. They have provided a moment of solace to each other, but no happy ending is to come. Happy to finally feel detached from the world, they are now free to kill themselves. Ironically, on the side of the building, a poster invites youth not to sniff solvent, as a miserable effort to solve the problem.