As I have mentioned many times before, the nucleus of the Japanese movie industry has always been the (family) drama, with the entries in the category being innumerable as the local filmmakers keep producing titles of the genre non-stop. And while the overwhelming majority of these movies are well shot, building on a legacy of decades, they also tend to be quite similar, to the point that is very difficult to find ones that stand out, particularly after the contemporary style, as dictated by Hirokazu Koreeda, started dominating the field. “Double Red” is another film that falls under the exact same classification. Let us take a more thorough look, however.

Double Red is screening at Skip City International D-Cinema Festival

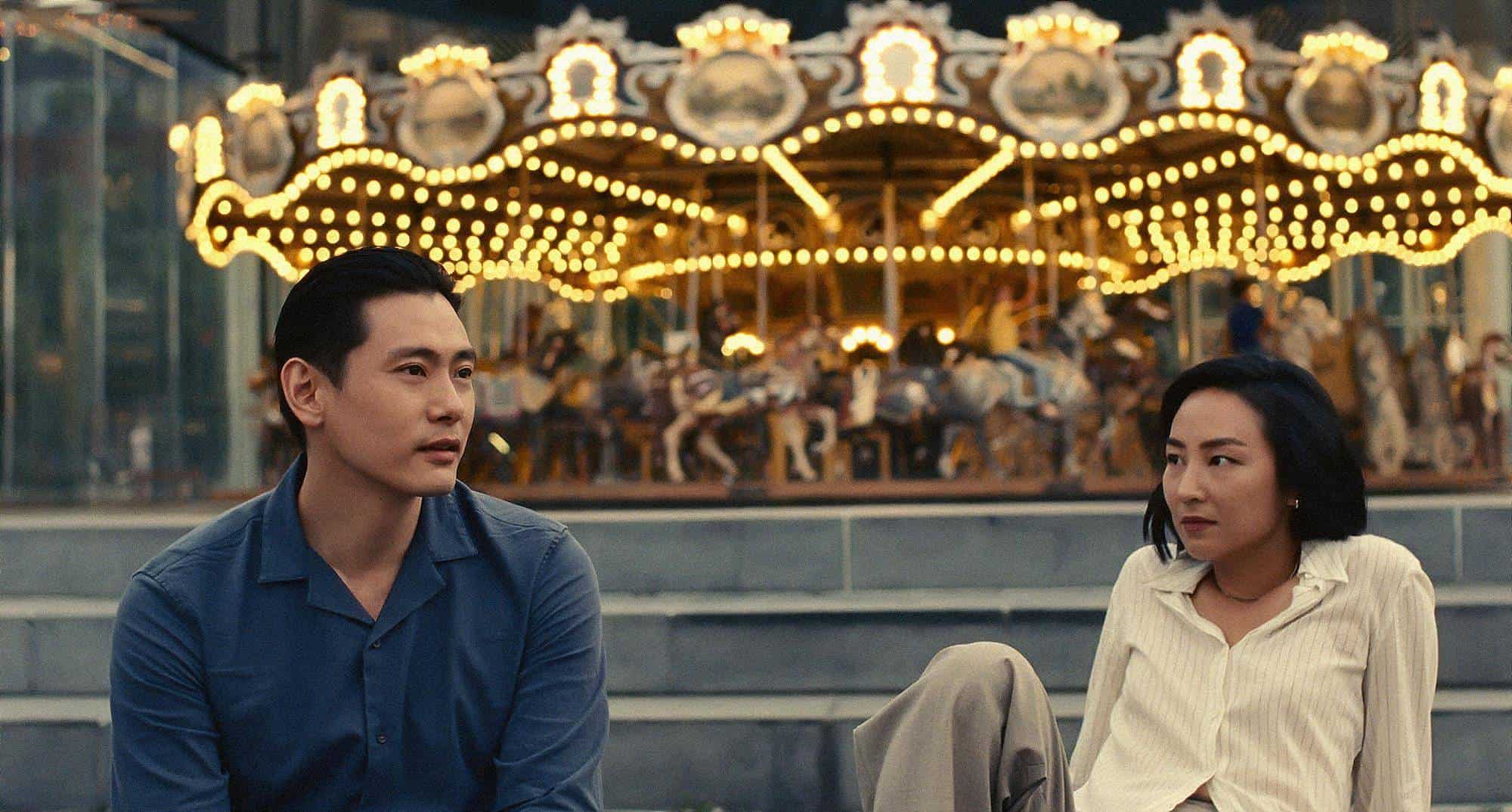

Bunsaku and Konosuke were really close friends, who also worked together under the latter's childhood friend, Natsume, a fIlm director who, as the story begins, has committed suicide. Both their grief is immense, but their situation and the way they try to cope with their grief, completely different. Bunsaku stays in Tokyo, and with the help of his ever-patient girlfriend Suzume, manages to gradually get in terms with the incident. Konosuke on the other hand, moves back to his hometown, without saying anything to no one, and starts working at a florist's. Then a parcel addressed to Konosuke arrives at the place he used to live with Bunsaku, from Tsukugawa, who was the cameraman on Natsume's film, containing her last recording.

Hachi Nekome directs a film about grief, and how people cope or fail to cope with it, with Bunsaku and Konosuke mirroring the two sides of the coin. In that fashion, probably the most interesting part of the narrative is the shadow Natsume casts upon those left behind, even after her death, the impact the lack of her presence causes, in a style that deems her as a kind of a ghost essentially.

What Nekome also highlights is that the lack of communication, in fact from all three of the protagonists, being the source of all their blights. Nekome could not speak before committing suicide, Konosuke could not afterwards, with the same applying to Bunsaku, who managed, however, to speak in the end due to the efforts of Suzume, who essentially forced this communication, with her presence highlighted as rather catalytic in the movie.

At the same time, and in a rather pessimistic fashion, Nekome also shows that not all gaps can be bridged with effort, and that sometimes, when the glass breaks, it can never be fixed again.

In general, the presentation of the comments here is quite appealing, as is the case with the overall atmosphere, with the somewhat bleak cinematography and the slow pace fitting the general aesthetics nicely. The additional elements of the dead filmmaker and the bookstore that is also a small print house add to the story, while Sodai Kadota as Bunsaku and Soichiro Tanaka as Konosuke give fitting performances, with their antithesis working really well.

At the same time, however, and although there is no particular fault with the movie, there is also nothing that stands out, neither in the comments nor the cinematic presentation, to the point that “Double Red” is quite easy to watch, also because at 65 minutes, it definitely does not overextend its welcome, but also one that the viewer will almost immediately forget after watching. The fact that films in the same style are a dime a dozen in Japanese cinema, also does not help.

Hachi Nekome is a good student of Japanese indie cinema, and “Double Red” is a testament to that fact. Moving forward, however, she will have to find a way to make her films stand out, if she wants to have an impact in the industry.