When Erik Matti's “On the Job” premiered in 2013, it shortly became an important title for many of the Filipinos. With the image of the corrupted landscape of Manila captured in a gritty, dark lens of noir-like thriller; with cops being paid off, prisoners used as hired guns, and politicians as gangsters, the film encapsulated the energy of the real events on which it was loosely based on. Once again, Manila became a violent and hostile place, a depiction that Filipino filmmakers lean towards with an obvious motivation in mind. The blood is there and it deserves representation.

Several years later, Matti comes back with the informal sequel to his story. Premiered in the 78th Venice Competition as a sole representative of Asian Cinema, his “On the Job: Missing 8” became a 208 minutes-long take on the current state of corruption, journalism and politics in the Philippines. This time around, it is set not in Manila, but at a provincial town of La Paz, where Matti lampoons the very severe network of connections, and questions the integrity of the dynamics between politics and journalism. Told as a narrative of gangsters, it re-imagines a story based on real events, that of the Maguindanao Massacre from 2009, when 58 people were kidnapped and killed. Most of them were journalists, who stood their ground against the government, which resulted in their death.

“On the Job: Missing 8” is one of the most ambitious of Matti's projects. He unfolds his narrative through a vast range of genres and forms: a prison film, gangster movie, journalism criminal, but then again, a character study or a portrayal of the city. When La Paz is shaken by the disappearance of the journalists, this is Sisoy (John Arcilla) – a local radio star shaped through his loyalty towards the mayor Eusebio – who is about to set his private investigation to find his colleagues, but also his own identity as a man of truth. Matti navigates between genre expressions to grasp the essence of Filipino interrelations, the sweet unbearableness of everyone knowing everyone and its aftermath for the everyday reality. And since it is 208 minutes that the film has to offer, the intensity, depth and clarity are there. The only thing one has to do is to plunge oneself into the narrative and take it as it is.

“On the Job: Missing 8” received a standing 5 minutes-long ovation after its premiere screening at Lido and was praised for its acting, with the main actor, John Arcilla, being awarded the Volpi Cup for his performance. After its premiere in Venice, “On the Job: Missing 8”, as well as “On the Job”, will appear on the HBO GO platform from September 12th onwards, where they will be streamed as a series of 6 episodes.

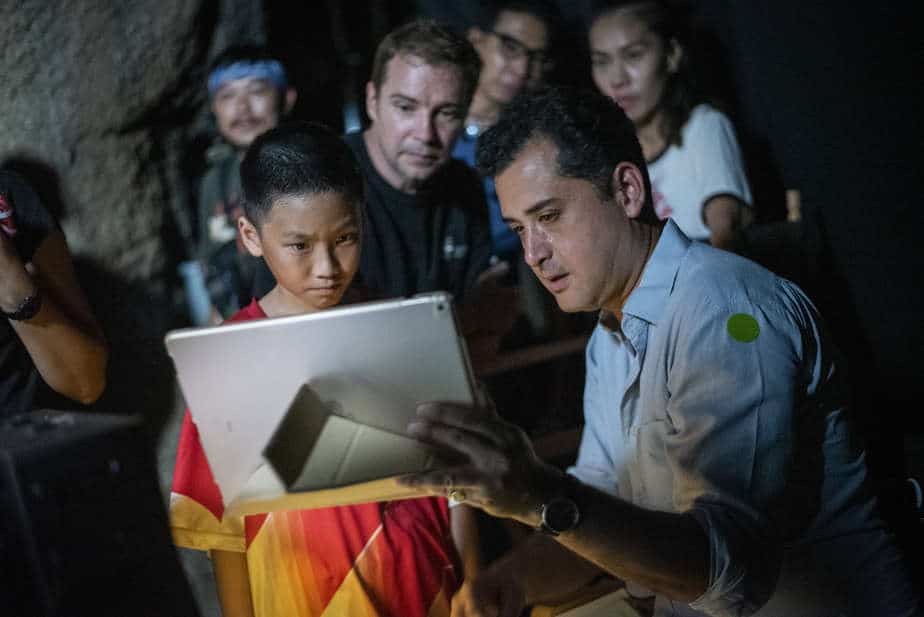

We managed to talk with the mastermind behind the project, prolific filmmaker Erik Matti, during the just-finished Venice Film Festival. In an exclusive interview, he talked us through his inspirations for making the second part, the idea of encapsulating the corruption in the Philippines (its origins and current state), grasping the visual language of both Manila and La Paz, and generational gaps in his country.

The interview was conducted by Lukasz Mankowski with a help of the Philippines-based journalist Jason Tan Liwag, who offered priceless consultation.

Both parts of “On the Job” reflect on the real events and show generational corruption in the Philippines over the years. What changed in the creative process of the second part?

Concerning the first part, the process for the second one took a while. Not just in terms of scale, but also regarding approaching the theme. Even scripting was more difficult. This time around, we [Erik and his scriptwriter and wife, Michiko Yamamoto] decided to focus on journalism. We spent a lot of time doing interviews. We had a long investigation of our own. And it wasn't easy; it was tough to find the inner workings of journalism. We divided the writing process into three segments.

The first one was the interviews with journalists. The second one was the online research. And the last one was additional research on things we couldn't find online, but we know that they exist. For that, we hired special researchers so they could help us look further into certain topics we wanted to include in our story.

The earlier drafts of the script were denser in terms of depicting journalism, as I was quite vicious in my attempt to discuss the issues related to journalism in the Philippines. But it made the script too big. So we had to get rid of the national angle and, instead, focused on the small-town journalism. That sparked our interest more than the national TV. Primarily because in small towns like La Paz, what's really interesting is that you have journalists who are not big names. They're below the mayors or governors, and eventually, they exist in this universe as the mouthpieces for those who are in power. A lot of times, these journalists lose track of what it means to be journalists. Only later do they realize they've already sacrificed their integrity as journalists. It is the moment when they become propaganda tools for the politicians.

In the first part, you focused on the environment of Manila. This time around, it is the provincial town of La Paz. In those two cities, there is a very peculiar contrast in the depiction of violence. Manila is very hectic, abundant in literal violence, very noir-like. Meanwhile, violence in La Paz isn't shown directly; it's more systemic, institutional, at times even spiritual. How did you approach the depiction of the violence in both of these environments?

It was quite deliberate to make a distinct difference between Manila and La Paz. And the biggest difference lies in the city itself; the milieu lies in the city. In Manila, things are grittier, even visually. The way we decided to capture the city was quite different from the approach towards La Paz. That's also apparent in the way we depicted prisoners-assassins. Being in a national penitentiary is a lot more unforgiving for their long-term situation. While in the second part, it's a prison set in the countryside, it has a more homey feeling.

There is also a stark difference in the way we presented the image of prisoners being brought out of prison to kill. The first part talks about being a professional assassin, with a set of rules that define how one should commit murder. And in the second part, since in the smaller cities people are into more petty crimes, we decided to show them simply as good followers, far from the image of the professional hired guns. They don't do much planning, do they? So it becomes something of a black comedy when they go for their killing mission, but it doesn't end up as smooth and as efficient as it should be. When they dig the hole, it's too shallow; they hesitate with timing as to when to attack the car; they didn't plan to kill the witness. There's a lot of randomness to the killing they commit, as opposed to the killers in Manila from part one.

More than just the idea of journalists being in the countryside, we felt we needed to provide a contrast on the visual ground as well. We had a new story and it needed a different texture. Of course, most of the stories we picked out from our research were grounded in the countryside. “On The Job: Missing 8” comprises a composition of several true events. That includes the infamous disappearance of people related to the Maguindanao Massacre from 2009, when a lot of journalists, who were on the case of one candidate running for the mayor's seat, were slaughtered, together with their family and relatives.

Courtesy of HBO GO.

What's more is that in the film, one shall simply not make it out of La Paz alive. And ironically, some of the characters desire to leave the town for Manila. And if we remember Manila from the first part, well, it's not really the place to go.

Many people like me, as I also come from the countryside, emigrate to bigger cities because we want to find something in our lives. When I decided that I want to make a career for myself as a filmmaker, I wanted to go to the place where the big things happen. At first, of course, it's tough. I worked as a production assistant and assistant director for 6 years. Sometimes you might never be discovered nor be allowed to do things you really want to do. But sooner or later, you start to find out how the city works. And if you come from a smaller city, you might use your background to get what you want. Because you get the idea of how to work with the space and its people. La Paz is that kind of place that announces itself as the cleanest city, the most efficient one. But then, underneath all of that, there are so many nasty things waiting to be discovered: corruption, crime and all these people trying to keep that order. But if they move to a bigger city, it only means that it will still be happening. Even more so.

That leads me to a question – where did the corruption start in the Philippines in general? What are its roots?

The corruption is systemic. There is one scene in the middle of the film when it sort of discusses the roots of it all. It's an eternal cycle of corruption; no one is accountable for anything and everyone is forgiven or forgotten. So it's systemic, but it dates way back. In the film, there is a link to the Marcos era, a period when it all started. At least most people feel it that way. But more than that, the system of corruption exists mainly because we're such a small country. Everyone knows everyone. That's why we decided to depict the dynamics of corruption this way in our film.

Even if you're a prisoner, you'll get to know the mayor; if you're mayor, you'll get to know major celebrities or journalists in your town. It's such a small place! Everybody gets to know everybody. And because of that, things like impunity or non-accountability happen all the time; one simply doesn't want someone else to be accountable for that thing or the other. I was asked a while ago: “Will we ever see the end of “On the Job?”. And the answer is, that we don't think of sequels every time we write “On the Job”. We write it as a stand-alone film. But with corruption as the main theme, it might never end! There are so many stories about these characters. They have moral dilemmas and their moral compass gets challenged all the time. So perhaps it will never end.

Coming back to your question. Where did it start? For me, it started way back when we were still a colonized country. We had so many conquerors, starting with Spain, then Japanese, Americans. We've learnt to be accommodating to all of these ‘kings' that took our country. With that, of course, corruption starts. You want opportunities for your family? You befriend the Spanish authorities. It really starts there and just goes on and on, and it snowballs. Before you know it, you're stuck in this corruption cycle. It gets rid of your integrity and credibility and you don't even realize this.

Courtesy of HBO GO.

Since everyone and everything is connected, was there any moment for you that you felt you're getting too close to something or someone? That it's becoming too dangerous?

Both of the films talk about characters based on real people, but we don't call them by their real names. We would even whisper that to the actors, (laughs), who their characters are based on so that they could start making research and realize how these people are in the real life. But at the end of the day, in the Philippines, we're not like Japan or Korea, where there is a strong sense of the culture of shame. We don't take shame that seriously. If there are some suspicions regarding corruption, one can easily resign. We're more like American gangsters. Movies are based on gangsters' lives in the Philippines and sometimes, these real gangsters would take their families to the cinemas to show off and say: “look, that's me on the screen!”. As long as you don't call them by names who they are, they just let go of the fact that it's their atrocity being pictured on the screen. They can even drop you a comment, that you depicted it in the right way! That makes us safe. And of course, it's also wrapped up in a lens of the genre. It becomes sleek, not too real, so it allows them to look at it as a movie, not just the image of who they really are.

There is also a recurring motif in the film of the dynamics between fathers and their sons, and the obsession and fear of one being better than the other. Where does it come from?

In the first “One the Job”, I wanted to portray the relationship of mentors and protegees. At the time when we wrote the script for the second part, I wondered if I can continue that trope by exploring the relationship between the father and the son, but also in the friendship among two journalists, one being better at what he does, but the second one being more popular. The dynamic is based on constant friction. Even in prison, it's the big brother using the other guy to do the killing; in politics, the son is being more ambitious than his father. In both parts, this is quite constant.

But our focus wasn't set on the aspect of going more into corruption. Rather than that, we wanted to portray the inability to become better in an environment like this. Bernie might in fact be better than his father and make the country a little better. But it's his father that stops him from doing so; he's suppressed so that any sort of change won't happen in this society. And then there's Sisoy, who rediscovers himself as a journalist. His close friend disappears and he starts getting on the right track. The hope for a change is there, in the ambition of both Sisoy and Bernie, but will this change ever be allowed in a system like this? With all the manipulations coming from Bernie's father or Pacheco, it shows there is barely any margin to do right. And it's also so difficult to resist the charm of corruption, as it opens so many doors.

There is also a personal level when it comes to the mentor-protegee relationship. I've been mentored as a filmmaker and if you're mentored as a filmmaker, part of you is influenced mainly by the aesthetic of your mentor. As a disciple, you want to use all the knowledge coming from your master, but at the same time, you want to bring it further and become better than the mentor. That being said, I also mentor a lot of directors. As a mentor, you want to maintain the kind of aesthetic you feel is right for cinema, but you also do realize that all these protegees have their sense of aesthetic, that they want to find a name on their own and leave a mark in the industry for themselves. A lot of times, that's where you have to work around each other and see whoever gets to what they want first.

Courtesy of HBO GO.

In the film, you navigate between the gangster movie, prison film or journalism criminal. What was the most challenging in balancing between these sub-genres?

My filmography in general is a total mix of so many things. Mainly because I'm not the kind of filmmaker who sticks to one type of film and then builds a career on doing different envisions of the same thing. As a filmmaker, I cherish the pursuit of exploring cinema. With “On the Job 1”, I wanted classic cops vs robbers, reminiscent of Melville or Johnnie To, as I was a big fan of that aesthetic. It became very gritty and dark, not only visually but also thematically.

With the second part, there is this recurring line stating the idea that politicians are essentially gangsters. It made me think about my aesthetic pursuit, that I want this vibe of American gangster movies of the 70s or 80s, sprawling, huge, lots of Scorsese in it. Even the music was selected in a way it would provide irony and contrast to what's happening on the screen. I also wanted to include classic standards – Frank Sinatra, Tom Jones, Johnny Mathis – because it also gave a more gangster flick to the whole. Aside from that, we used lots of single tracking shots for most of the scenes so we could establish a particular setting and the atmosphere. All of that was designed to strengthen the essence of the gangster genre.

I know that you planned the second part to be partly in the dialogue with the phenomenon of fake news, but as a matter of fact, the elections in the Philippines are just around the corner. How do you feel the audience will reflect on these issues related to corruption and politics?

This is how cinema works for us, really. When someone watched “E.T” during the time it was released, all the events around at that time dictated how they felt about the film, right? And when you watch it 10 years later, after watching “Alien” and many other films, it also determines how you take the film, as it comes to you again with different contexts.

It's the same with “One the Job”. In our minds – filmmakers, producers, writers – the film exists as an exploration of journalism, corruption or fake news. But now, that it's released when the elections are just right around the corner in a few months, I'm curious about how the audience will respond to it, with a lens on all these issues depicted in the film. They won't be just looking at the case of fake news that you've heard about in the past five or six years and the constant barrage of untrue stories, but this time around it will be connected directly to the domestic ground and elections.

I want to see how people react to the film, with both of these things in mind – fake news and elections – and realize how these two things intermingle with each other. Thanks to the elections on the horizon, the film became more timely, more urgent, and more immediate. It became possible to connect the dots and maybe people will see what is possibly coming to our country.

Courtesy of HBO GO.

There is also a lot of attachment to the place, where one's home is. Roman repeats his wish to be back home; a sense of locality ties the bounds of La Paz's community. But where exactly is this home?

“One the Job: Missing 8” is built around the final confrontation between Roman and Sisoy in the end. Both protagonists traverse the whole film, they carry it unto themselves, but in the end, they confront and the question is – who do they represent? The last election in the Philippines polarized everyone on social media. Some people want to fight for what's right and they want to make a statement, loud and clear, how the country should change. And there are people, who just want to keep quiet and live their lives simply, whether there's a new government or not. Both of these groups are represented in Sisoy.

It comes from the fact that I've been quite vocal on social media about criticizing the current government, which sometimes resulted in a detriment on my side, as many trolls started to attack me. At the same time, my relatives often ask me: “Erik, why wouldn't you just be quiet?”. They say, “Live your life, you have a good one. You have a car, a house. Why do you have to fight for something you cannot win?”. And that's Roman. I'm doing all of these not to say journalism is corrupted or to change La Paz. I just want to go home. (laughs) I just want to go home and I don't care about your beliefs nor your principles. I want to be back home, with my family, start taking care of my farm.

And then you have Sisoy, who at first has forgotten what home means, but then the experience changes him. He becomes ready to be the fighter he used to be. He finds his life again, one that he forgot he had. But before that, he supported the mayor. He and Roman represent two polarizing opposites of the Filipino society who both fight for a certain image of the home on social media, every single day.

A friend of mine, a journalist from the Philippines, described “On the Job: Missing 8” as the ghost story of the first part.

That's something new I hear about the film. But I agree. Mainly because our past has dictated what we are now. There is this constant line in the film, that says ‘never forget'. We can easily forget the new cycle, but the thing is not to forget the dead people. Because we easily forget. And we fight for it, we fight for something today. Two days later, a new article comes out. The world moves on. And in the film? The missing 8 hasn't been found. There's a piece of big news about the typhoon. People start forgetting. Those who remember? They're looking right in the eyes of the past all the time. Constantly. Only those who never forget can bring some change to certain things. Sisoy never forgot. Even if the police went on to fool around, even if the typhoon arrived, even if all these cycles have changed into something else, Sisoy was always there to find his colleagues. That became his mantra. He decided that nothing will get in his way to forget about what happened to them.

Midway into the film, we see the roots of the disappearances, the ghosts. The disappearances have hounded us for years. If you look at the photos of those who disappeared – these are the real people, real photos. We didn't take them for the film. These are real people who disappeared. And the audience needs to be constantly reminded that the case was not closed. Those involved in these cases have been in the government up to now, but no one's holding them accountable for what they did.