By Elise Shick

The artistic zeitgeist of the Japanese New Wave from the late 1950s through the early 1970s was formed by the proliferation of avant-garde and experimental Japanese films that pursued radical inquests into political, social and cultural changes[1] as one can study via the philosophical and aesthetic presentations, particularly in the works of Nagisa Oshima, Hiroshi Teshigahara, Shuji Terayama and Toshio Matsumoto. The emergence of Japanese ‘I-films' (personal documentaries) in the early 1970s as the out-turn of the Japanese New Wave marked a historical turning point from public films to the private cinema of personal expressions and individuality[2]. Inspired by Jonas Mekas's “Reminiscences of a Journey to Lithuania” (1973), the poet and independent filmmaker Shirouyasu Suzuki's amateur home movie “Impression of Sunset” (1975) and his later distinctive work “15 Days” (1980) are amongst the personal documentaries that divert from conventional documentary filmmaking and turn the fascination of ‘self' into a phenomenon in contemporary Japanese cinema.

This essay is part of the Asian Cinema Education Film Criticism Course 2021

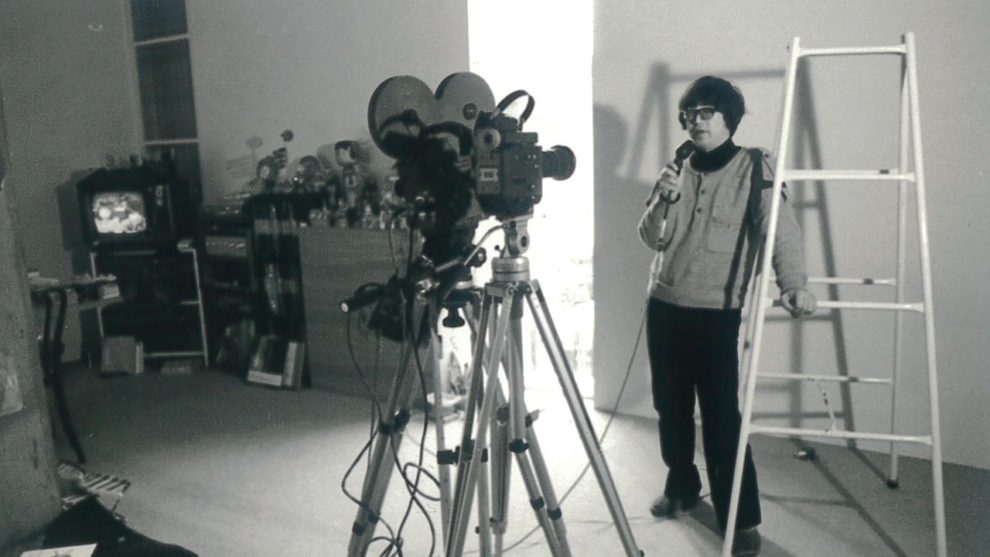

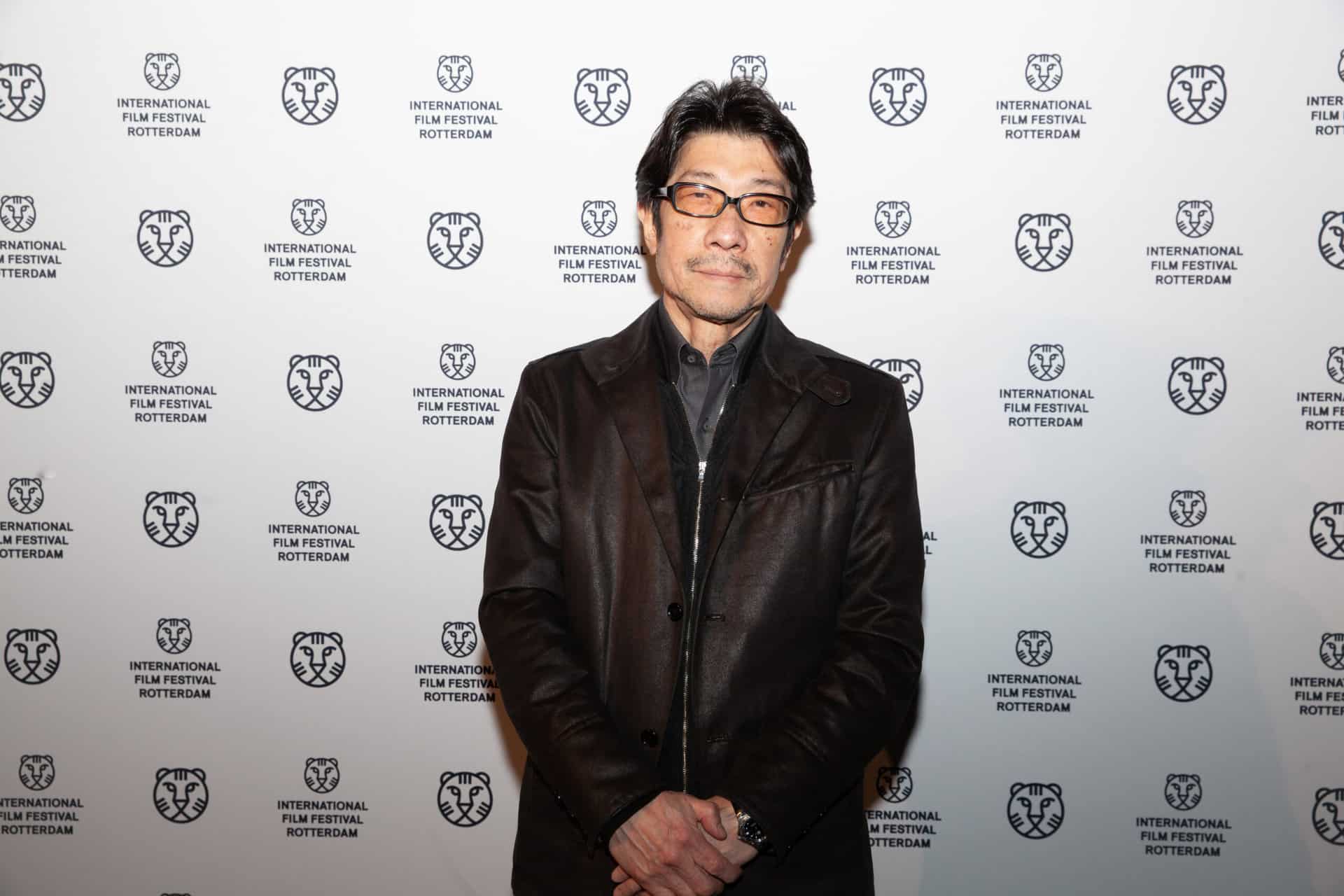

“15 Days” was shot in 15 days from November 19 to December 3, 1979 – two years after Shirouyasu Suzuki left NHK (Nippon Hoso Kyokai, Japanese Broadcasting Company) where he worked as a cameraman for 15 years, filming mass-oriented, ‘official' documentaries that held a journalistic point of view. The breakaway from presenting a set of staged, curated truths for public interest brings about a drastic change in the filmmaker's cinematic language and filmmaking approach in which the emphasis on subject/subjectivity (the cineaste's critical stance is reflected in the questioning of their own position and the problematising of the authorial agency through the principle of subjective reflection and personal engagement) becomes the most prominent characteristic that informs the narrative, visual and editing styles in “15 Days”.

I walk in Shinjuku and say “I'm walking in Shinjuku'

I soon forget where I am walking in the crowd.

Is it about rejecting others and doing everything alone?

It's like being part of a movement that you can't escape.

You are nothing but literature locked in a room.

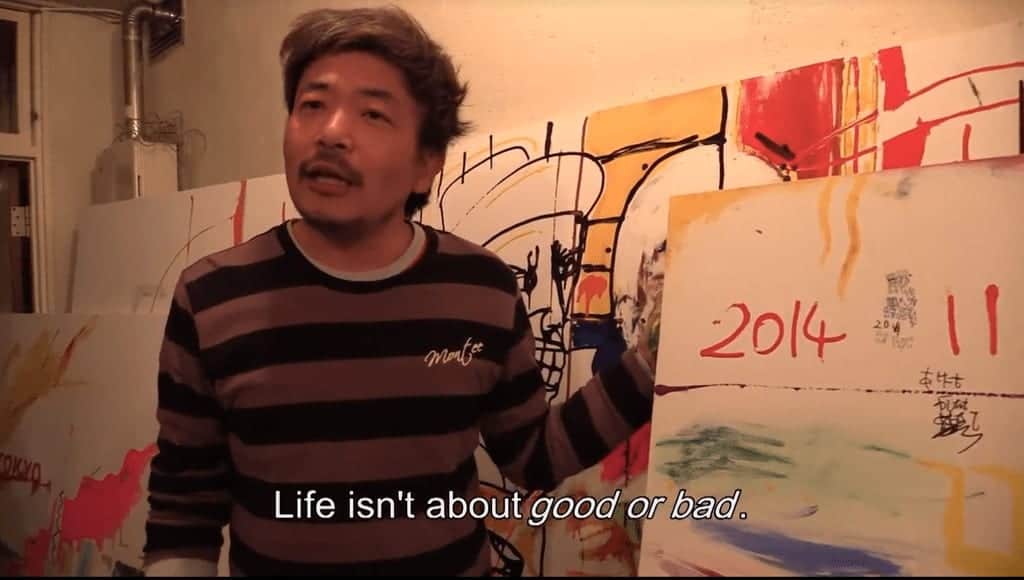

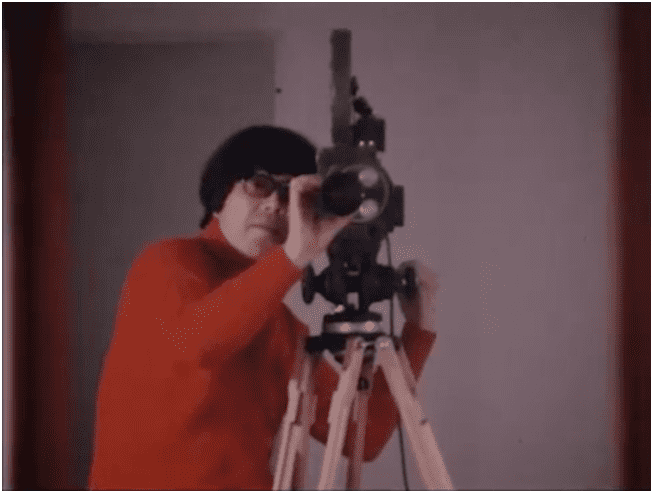

Sitting alone in the centre of the frame, Shiroyasu Suzuki films himself in front of a Beaulieu 16 camera. These unscripted monologues unfold themselves as the director/subject/narrator opens up his private life through the recounts of his daily activities. Losing one's privacy also means revealing a sense of vulnerability and displaying certain embarrassment. The act of self-filming and exposing oneself in front of the camera involves some degree of risk-taking, yet only in this risky territory is the reflection of ‘self' rendered possible through the gaze of others (the viewers) – such is the mirror effect between the one being filmed and the one watching, facilitated by the presence of the camera that balances out this power relation. This private sphere of the subject's mental landscape manifested in front of our eyes is also a space where the quest for truth takes place through close self-examination – a process in which the subject scrutinises himself as an independent entity (the ‘self') and also in relation to the outside world (the society in which we are part of yet cannot escape from) in hope of locating his private cinema in the robust scene of mainstream cinema against the backdrop of progressive counter-establishment movement in the post-WWII Japan. Suzuki's self-confrontational journey demands endless questioning, as seen in his narration that repeats itself in a loop from one day to another, yet leading both the subject and the viewers to nowhere definite even though we are being consciously pushed forward by the design of linear, chronological order of time (the display of dates on screen) that attempts to create a series of spatially and temporally continuous scenes. Such looping effects embody the brevity of human life, the cycles from day to night, the multiple rebirths of the present, the deconstruction and then the reconstruction of the ‘self'. The essence of this personal documentary does not lie in the presence of a defined framework or theme but in its transcendental, contemplative and experiential states of navigating through one's existence and personal voice.

The camera language in “15 Days” plays a crucial role in moderating the power dynamics between the director, the subject, and the viewers. Set predominantly on a tripod, the 16mm camera is always placed in close proximity to the subject where he is framed in the middle of a medium shot as if he is performing in the centre of a stage for the spectators. The composition of these long, still shots confines the subject to the space within the frame, manipulating us, the viewers, as a tool of surveillance to look into the subject's private life. As the gaze of the camera transitioned from averted (the subject speaks with his back facing the camera as if avoiding the gaze of the viewers) throughout the first 34 minutes of the film to extra-diegetic (he looks into the camera and speaks directly to us) in the second half of the film, the power is gradually handed over from the viewers to the subject. By breaking the ‘fourth wall', the subject identifies with the gaze of the camera and liberates himself from its imprisonment. Such breakaway enables the subject to see himself for the first time as ‘other' – an important stage in ego formation and self-reflection (the mirror stage), as coined by the psychoanalytic theorist Jacques Lacan. The camera stays still when the subject studies himself through this mirror stage; the camera moves when the subject becomes the look of the camera, interacting with the outside world from the director's point of view. This unequivocal shot language and role-playing set forth a clear juxtaposition of the interior look and the exterior look of the film. When these visual styles are placed next to each other, it draws a parallel relation to the idea of ‘self' that comes into view in the private sphere versus the attempt of this ‘self' to integrate into the larger society.

From time to time, Suzuki speaks to the camera about the meaninglessness of making a self-serving film and the sense of apprehension he feels towards himself. The actualisation of ‘self' is embedded in the action of negating the ‘self' when a double of the self emerges from Suzuki's splits of persona: the role of the director versus the role of the subject. This pull-push relationship occurs when the double self alienates from its original in order to be examined more closely than its original. Such self-examination brings about the conscious questioning of ‘I' (the filmmaker) in the eyes of ‘others' (audience reception) – an introspection that makes the transmutable idea of ‘self' a topic worth studying. Suzuki's cinema of privacy suggests that personal expressions can be universal in the process of developing oneself as a phenomenon, if such phenomenon is treated as a set of reality[3]. Instead of employing the common interest shared amongst local viewers in the creation of his artworks, which will again end up reproducing one of the conventional documentaries that already exist in the mass market, Shirouyasu Suzuki boldly reverses the process: to kick-start a novel form of documentary and work his way slowly towards gaining some sort of universal recognition through his poetic meditation in “15 Days”. Here I would like to end this piece of essay by quoting the philosopher Plato:

[…] why should we not calmly and patiently review our own thoughts, and thoroughly examine and see what these appearances in us really are?[4]

[1] H. Benjamin, ‘Late Japanese New Wave Documentary and Cinematic Truth: Charting the Theory and Method of “Graphic Sensitivity” Towards Cultural Otherness', Colloquy Text Theory Critique, no. 24 , 2012, p. 79, https://www.monash.edu/__data/assets/pdf_file/0007/1772611/hegarty.pdf, (accessed 13 October 2021).

[2] Y. Kiki Tianqi, My Self on Camera: First Person Documentary Practice in an Individualising China, Edinburg University Press, 2018, p. 8.

[3] S. Claudia, ‘Approaching The Cinema of Privacy of Shirouyasu Suzuki', desistfilm, https://desistfilm.com/approaching-the-cinema-of-privacy-of-suzuki-shirouyasu/, (accessed 19 August 2021).

[4] Plato, Theaetetus, United Kingdom, Penguin Classic, 2005, p. 155.