Hewad (Arafat Faiz) is already a breadwinner at the gentle age of nine. Ever since the death of his father who was martyred (as victims of bomb attacks and air raids will be persistently called during the film), he is ‘the only man' who has to take care of his grandmother, mother and younger sister. The boy roams the streets of Kabul, day in, day out, to sell groceries, trinkets, snacks and pomegranates he is taking from the individual shop owners with the promise of getting a good price elsewhere. He is even delivering amulets from a nice, old mullah to those who need them. Hewad is pushing a shabby, heavy wooden cart adorned with the picture of his idol Arnold Schwarzenegger up and down the steep city streets during his rounds in the neighborhood. Behind one of the gates, the woman of his dreams lives. Not that he has ever seen her face. Her henna painted arm that ‘greets' him to take the orders and pay for them is enough for the boy to know that she is the only one.

The second feature film “When Pomegranates Howl” by Australian-Iranian director Granaz Moussavi is inspired by true events surrounding ‘a mistaken incident' in March 2013, when a helicopter killed two Afghan boys mistaking them for insurgents. The film closes with the archive footage from the Australian TV when the killing and the compensation to the families is discussed. Australian Defense Minister Stephen Smith speaks of “hundreds rather than thousands, concerning the country's economy”.

The minister's cold statement makes the skin crawl: a child's life has a price related to the country's poverty. “When Pomegranates Howl” shows the life in Afghanistan's capital as a never ending fight for survival, in which children suffer the most.

For her touching account of hardships the youngest endure, Moussavi has chosen to work with non-actors. Faiz fits perfectly in his role of a kid with big dreams and dedication to the hard work that feeds his family. His lack of experience in the field brings a sense of credibility to the story, helped by an almost documentarist approach that the director uses to show how a typical day of a child that had to grow up over night looks like. She also lets her main protagonist confront the western exploitation of war by letting him become the subject of one photographer's staged ‘reality' shoot, right after a bomb attack on the wedding he was working at selling pomegranate juice. It was the nature of the job that saved his skin, as someone who was outside of the festivity itself. But this encounter will make the boy dream of becoming a film star. Asked to document his life, he is given a camera, which makes him falsely believe that he was chosen to play in a movie, maybe even rubbing shoulders with his idol Arnold Schwarzenegger.

The story is told in simple, unchallenging tones, and there is a constant sense of a piece missing from the picture. That has a bit to do with the almost all amateur team of actors who can't unsee the camera, often aiming their gazes directly at the lens. Many faces from the Khabul chaotic, livid life penetrate the screen. Young men ruffle on the street, kids play with a kite amidst the town's ruins, those wealthier entertain themselves with rooster fights.

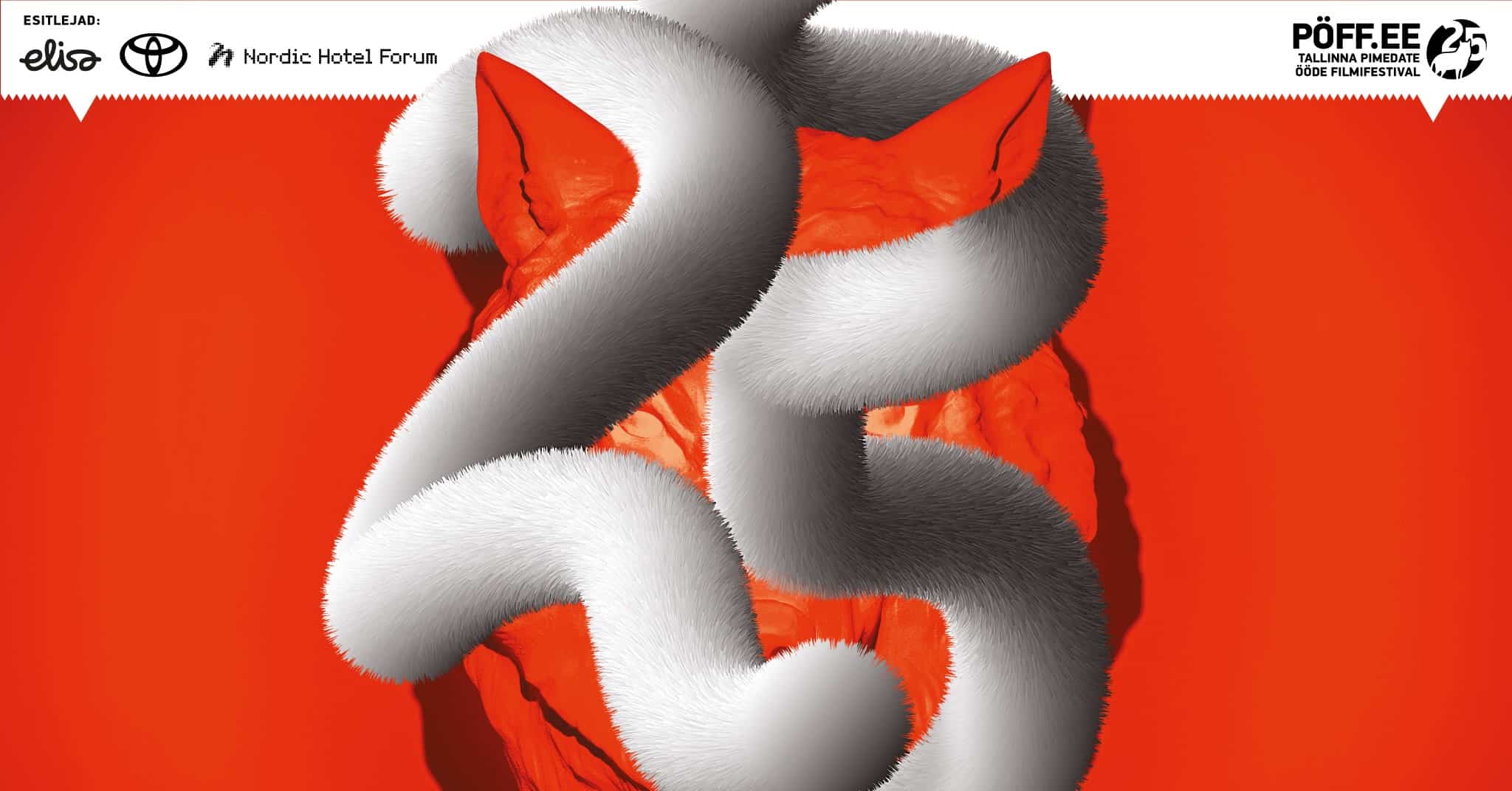

Granaz Moussavi's second feature is the Australian submission for the Oscars. We watched the film at PÖFF, where it was shown in the prestigious program Current Waves.