From its first shot, “Children of the Mist,” Diem Ha Le's award-winning documentary about the Hmong community's bride-stealing practice, plunges us into the daily life of a family from Vietnamese minority without any explanation. There is no exposition here, no text to give us context, no explanation about the people and their precarious place in the Vietnamese socioeconomic hierarchy, not even where they live. We only see that it is somewhere high in the mountains, where the mist is thicker than milk.

Instead, Diem lets us discover out everything by ourselves. Not through boring talking head interviews with her subject or other people of her immediate surroundings, but through interactions within the family she lives with and the interactions of the daughter, Di, with the ones around her. She accompanies the girl at school, where she goes in full makeup, as if wanting to show her budding sexuality and announce to possible suitors that she is ready for marriage. She also goes with her to a kind of teenager party where some of the bride kidnapping occurs. She even half-follows Di as she leaves with Vang, a boy she seems to like who promises he won't kidnap her. Of course, he lies and it seems that she half knows it. These observations are at times within the documentary interspersed with ones of the documentarian asking the young girl and her family about their choices, especially related to the bride-stealing practiced in the community, sometimes punctuated with self-reflective monologues by Diem about her relationship with Di and her family. These exchanges are always spontaneous, lending the movie a feeling of authenticity similar to the one achieved by Zhang Mengqi in her “Self-portrait” series.

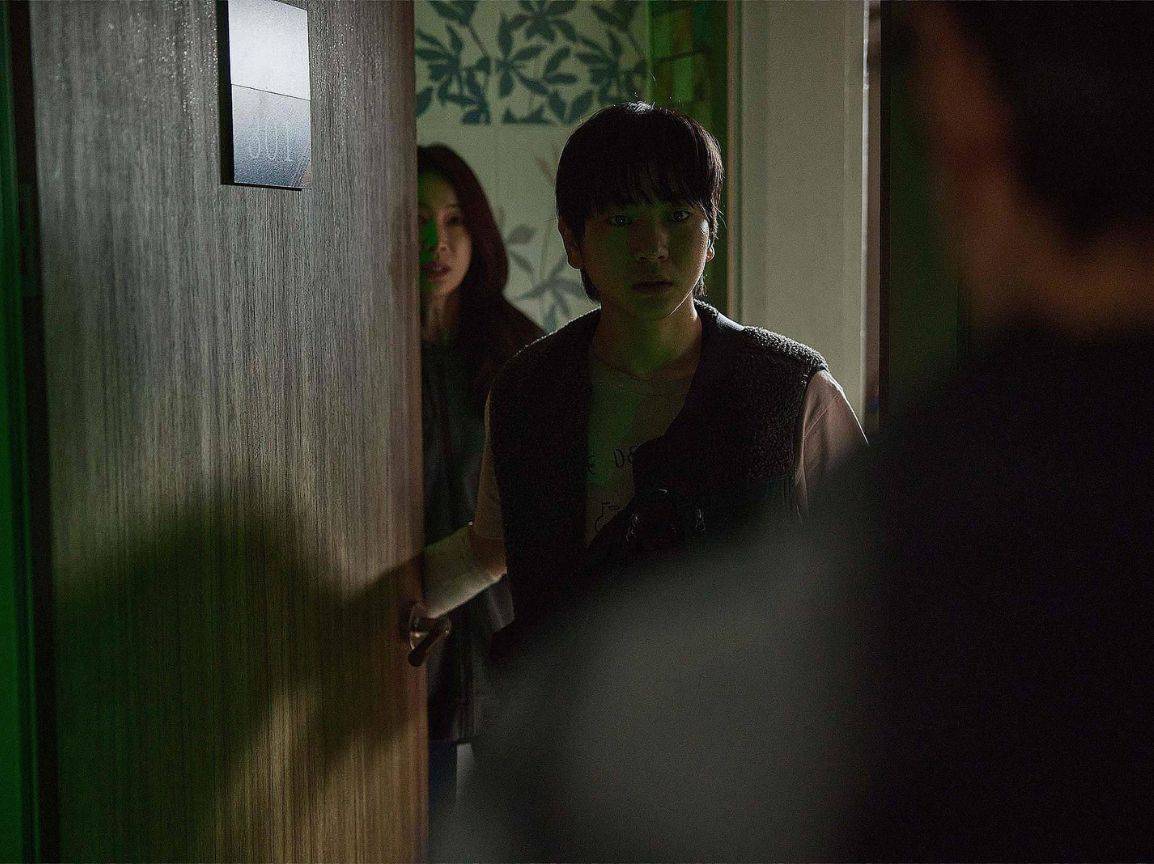

Rather than a study of a minority, “Children of the Mist” presents the viewer with an intimate and, what is more important, compassionate portrait of the relationship between a director and her subject. As the movie progresses, so does the relationship between the two women. This shows especially towards the end when Diem, with camera in hand, rushes to save her dear Di. She not only films as an observer to the goings-on in the family, but does everything she can to help the young girl. She urges Di's father to go and save his daughter when Vang kidnaps her. The father, drunk again, says he shouldn't meddle in the youth's life. And neither should she, his stern look suggests. She does the same, but to an even larger degree, when Vang and his family try to really kidnap the unwanting Di from her house. Ignoring her pleas and wriggling, they pull her towards their house, while the girl's parents sit idly, watching. Diem is the only person who rushes to help, trying to hold her friend, weaken the grasps of the invaders. Yet, she is almost attacked by none other than Di's father who looks like he is going to beat the director up for trying to help his daughter.

As enraging as Vang's stalking-like behavior and his parents' extreme violence might be, and trust me, they are to the degree that the movie should have a warning for triggering content, it is Di's parents who seem to be the real villains here. Alcoholic and proud of it, uneducated and seemingly against any type of learning, they care more about losing face in front of their community than the well-being of their daughter. That is why they are willing to sell her at the age of 14, simply because she has made a mistake to follow a guy home. Some might call this following tradition or Hmong culture, and to a degree it might be, but as Di's teachers tell her and try to explain to her parents a few times, the fact that something was done in the past doesn't mean that it should continued to be done. Especially if it is as abusive and damaging as kidnapping and forced marriage as is the case with bride-kidnapping.

Together with alcoholic and abusive, Di's parents are compulsive liars. Though many times the girl's mother tells her that she doesn't have to marry the boy who kidnapped her if she doesn't want to, even going as far as to give her advice how to break up with him without the family losing face, she starts verbally abusing her the moment Di tells Vang she doesn't want to be his wife. In the end, the girl's only support is Diem, her parents are drunkards who are willing to sell her for some booze, all the while complaining that no one is going to take care of the pigs when they are drunk, her neighbors too, seem to be drunkards to accept the bride stealing at a young age as something normal.

Diem is Di's only friend and she is not afraid to show that. However, this is not the type of friendship based on hierarchy between subject and director, as other documentaries might entail. Diem doesn't seem to accept the customs of the Hmong, neither is she uncritical of the actions of Di. At one point, she even goes as far as to say that she hates her because she behaves without thinking about the future. This seems to be admonition as much towards Di as it is to all of her friends, even the entire community, all of which seems to live for the day – drinking, partying, complaining. The “hatred” Diems admit, though, seems to be one based on sister-like love. She really cares about Di and wants to help her, but not in some savior type of way, in the sense of rescuing the girl from her abusive parents or calling the cops on them, would entail. She respects her young friend way too much to do that. Instead, she tries to give her strength to speak and fight for herself through the power of the camera and their conversations. And eventually, she does, rejecting both the marriage she somewhat chose, the position she was forced into, and, most importantly, the type of damaging tradition that has no place in the contemporary world.