Jennifer Ngo's debut “Faceless” tells the story of four people from different walks of like as they participate in the 2019 anti-extradition protests in Hong Kong. Simply called The Student, The Artist, The Daughter, and The Believer, for their identifiable characteristics, and wearing masks, hats and goggles to protect their identities form the police, especially after the 2022 national security law that sees protests and anti-Chinese sentiments as acts of terrorism, Ngo and her team follow them as they prepare for and join the front lines of the increasingly more violent protests which culminate in the siege of the Hong Kong Polytechnic University.

“Faceless” is screening at the Black Movie International Festival of Independent Films

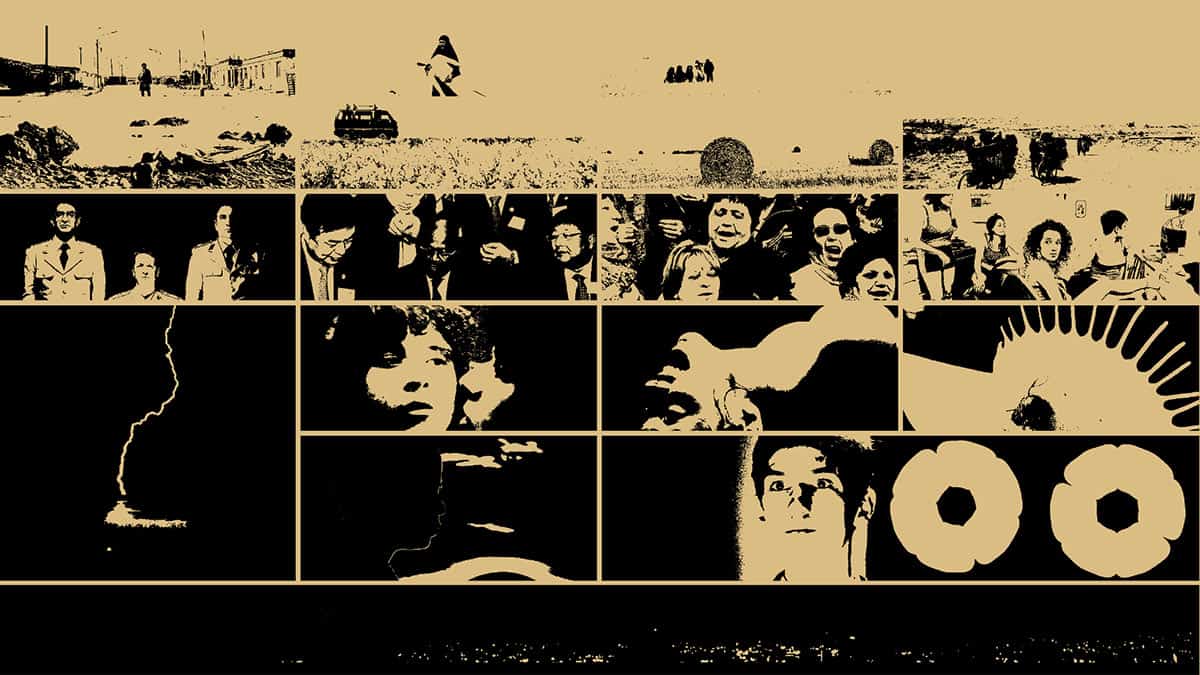

Though of different age and backgrounds, The Daughter is the daughter of a police officer, The Believer is a devout Christian, The Artist, a queer visual artist, and The Student, a possibly radical left high school student with a Zenkyoto-looking helmet, what connects them is their sense of identity. Though ethnically Chinese, as one of them admits, they don't see themselves as being part of China the country. Instead, they want to protect their identity and freedom as Hongkongers, which the Chinese government has tried to erode for the past twenty years or so. And as Ngo shows in a cleverly animated infographic about the rising frequencies of unrest, China-kowtowing Chief Executive Carrie Lam, and increasingly stricter pro-Chinese laws, they don't have much time to fight before Communist Party-led China swallows them and enforces on them everything that comes with it.

The protracted protests against the extraction bill point to another problem in Hong Kong society realized by the four people followed by Ngo – the police is an enemy. A violent and brutal one at that. We see this best through the interviews with The Daughter. Coming from a police family and taught from a young age to think of the police as friends and protectors of the people, through the months-long clashes with heavily armed officers, she realizes that they are anything but. Instead, they are cruel protectors of the repressive regime. This leads to one of the most touching scenes in the entire documentary when she recounts in extreme detail how her policeman father found about her participation in the protests, beats her, and throws her out of her childhood home, rendering her homeless. Nothing is ever going to be the same, she tells the camera, having realized that her father and her stand on the opposite sides of the barricade and would never be able to see eye to eye.

Each of the remaining three subjects, The Student, The Artist, and The Believer, open up about the internal and external difficulties brought by the prolonged protests, but, sadly, the movie does not linger on their stories. Instead, it glosses over them, or even worse, cheapens them at times through excessively dramatic music, unnecessarily stylish cinematography, and fast and sleek editing.

Take for example The Daughter's story from above. Instead of letting the viewer focus on her words and changing expression of her eyes, Ngo and her team decide to shoot the woman from numerous angles and splice some b-roll of rain puddles and other unnecessary things. That would've been fine, though unneeded, weren't it for the fact that some of the angles the cinematographer uses might be misconstrued as portraying the woman in a negative light. It should go without saying that this is far from what Jennifer Ngo and everyone else working on the movie try to say about the protesters, but this focus on style over everything else recurs too many times in the movie.

Midway through the film, as the skirmishes between the people and police start to become tenser, Ngo introduces to the viewer a set of participants in the protest known as “parents” and “navigators.” Though not on the ground with the masses, their jobs seem to be equally important. They first procure large quantities of sensitive and vital gear for the protesters, heavy duty masks, filters for them, gloves, and others, and deliver them to their “children” i.e. the young people on the frontlines. The “navigators” carry an equally essential function. Though staying indoors and not on the streets, they help the protesters by following the movements of the police, predicting where they will go next, and making safe routes through which the people on the streets can escape the violent police.

The two groups, “parents” and “navigators,” indicate the existence of a larger structure of democracy fighters and a much stronger web of collaboration between Hongkongers than the already large numbers of people on the streets might suggest. However, the director glosses this crucial aspect of the protest organization over, just like she does the emotional and mental weight of the constant struggle on the four people she documents. It is precisely through these promised and quickly discarded moments of nuance and depth, and not the unnecessarily sleek production, that “Faceless” fails to become a truly good documentary about the struggles in Hong Kong.