As Wang Yang's observational documentary “Transition – Space” opens, we see a landscape – a stretch of land marked with a few cranes and buildings in different states of completion. There is nothing unique or distinguishable about it, but we learn through a short text that it is located in the “mega-university town” Guodu, Xi'an Province in western China. It was once, most probably not long ago, a farmland, as we learn from the series of shots from high above the ground. The camera pans to show us the landscape, it is currently being redeveloped and “modernized.”

Transition – Space is streaming on CathayPlay

Not everything is shown from this elevated perspective, though. Very early into the documentary, we see the inside of a construction elevator and a set of hands that press the buttons to go down. It is as if we are the architects, who scanning their creation, have decided to come down to the ground and see how the people use their work. Or maybe we are one of the menial workers the movie shows us repeatedly? We never know, and, frankly, it doesn't matter all that much.

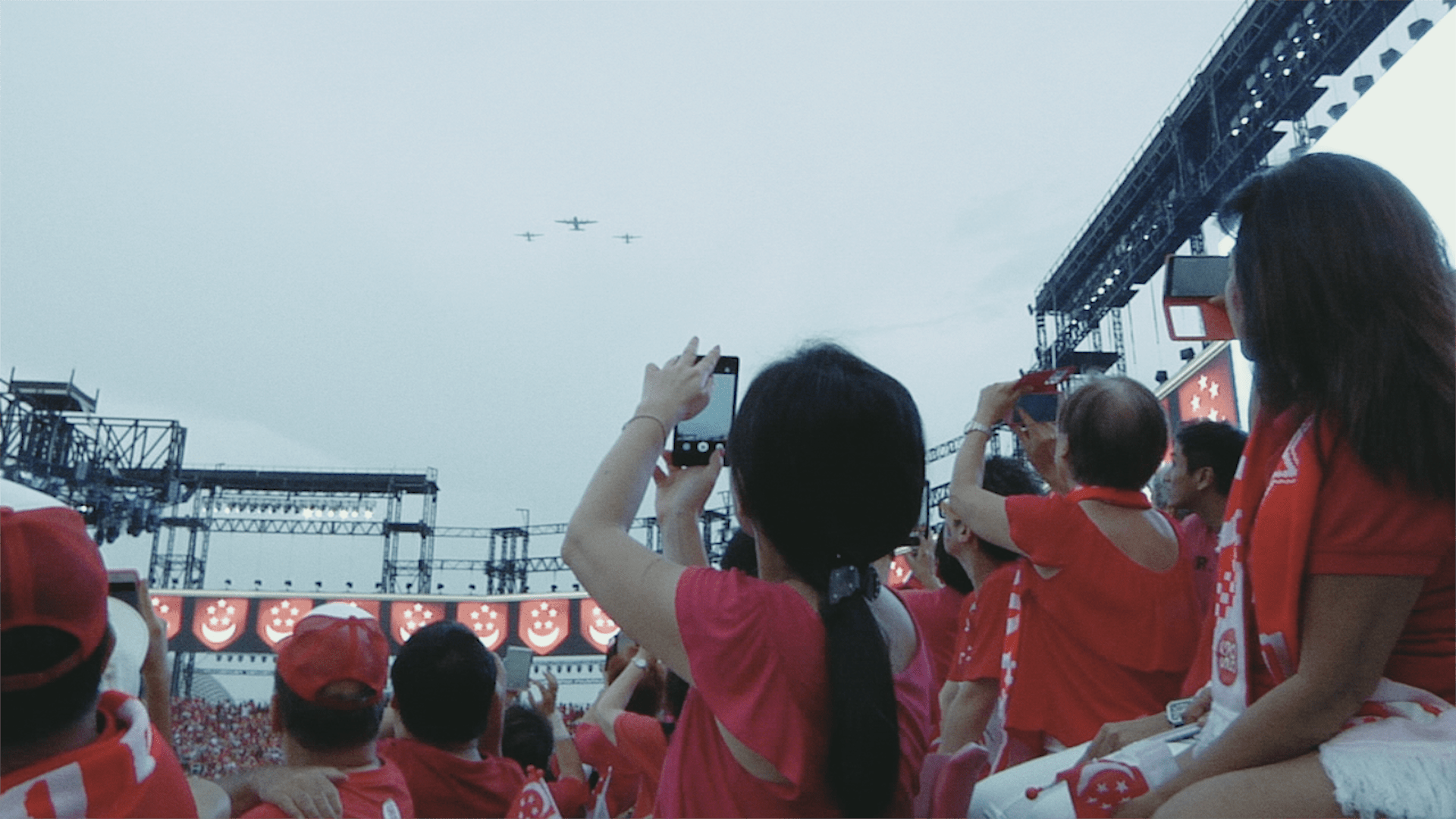

Whoever we might be, we visit different spaces in the place and witness the effects the changing landscape has on the people. We do that either through the steady, immovable gaze of the static shot or through the judgemental-yet-detached one of the slow vertical pan. Both of them, however, show the exact same thing – droves of people who don't engage with one another. All of them, be they students leaving the university grounds or old people training in the parks, act as if they are utterly alone.

Whether the people onscreen walk, run, stretch or dance, they do it in complete silence. However, as the camera shows us, it is not the type of silence that comes from respecting those around you, but from pretending they do not exist. We see this best through a long and rather uncomfortable dolly shot of rows after rows of people queued at what is probably one of the newly built supermarkets in the city. Though containing different people, they are all the same because they are all ghostly quiet and pretending like no one else except for them exists.

Apart from newly sprung buildings, what connects all spaces shown through Wang's camera is the deathly sense of silence. Irrespective of how many people there are onscreen, and at times there are hundreds if not thousands, there is this sense of extreme, even heavy, silence. We hear some environmental sounds, such as machines whirring or boomboxes playing music, but almost never any natural sounds, be they people talking or even insects buzzing.

There are only a few scenes in which we can hear people talking. One of them is of newly transplanted to the city village people who speak to each other and complain about one of their neighbors directly to the camera. It is as if, not yet been alienated by the experience of living in a big city, they have managed to protect their connection with the rest of the humanity.

This brief, shocking because of its spontaneity, scene is contrasted with the military-like one following it. Though taking place at a newly built karaoke club and containing the longest time someone speaks in the entire documentary, it looks, sounds, and feels as if taken at an army base. Instead of an army man, though, it shows a petty gangster-looking guy lecturing new employees on how to serve their new masters, the random visitors. Though sounding like a human speaking, it is anything but a conversation for it is one-sided and dehumanizing. Just like the entire unwanted transition towards alienated existence that “modernization” brings.