Even though it would take a while before the great social and political upheavals would define everyday life in Japan, many artists already sought ways to deal with the changed mentality in their country after World War II. With Seijun Suzuki perhaps being the most radical of them all, using genre cinema as a means to highlight issues like disintegration and consumerism, his colleagues also had invented new approaches within the medium to tell stories more fitting for the change which was ultimately inevitable. Director Shohei Imamura is most certainly no exception to the rule, with his 1960 feature “Pigs and Battleships” already presenting a harsh portrayal of his home country, its politics and its society, which he would continue in his next project “The Insect Woman”. In terms of tone a continuation of his former works, “The Insect Woman” would go further, exploring the “worker bee”-mentality, how it rewards ambition for the price of humanity and compassion.

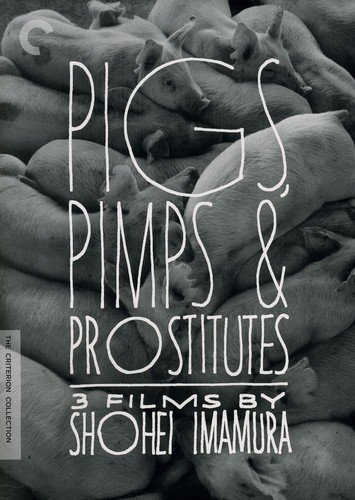

Buy This Title

on Amazon

The story takes place in 1918, in a small rural community, where a family is expecting a baby. As they are poor and their living conditions are tough, Tome, as the baby is called, has to help her mother as soon as she is old enough to do so, while also serving as a loyal “bedmate” for her mentally handicapped father. When she becomes a teenager, she starts working at a factory, where she eventually becomes a union leader and has an affair with one of the foremen. However, as she is fired for political reasons, she decides to try her luck in the city, leaving her illegitimate daughter with her father, who is against Tome leaving.

After a while, working as a cleaning woman and servant in a brothel, Tome (as an adult played by Sachiko Hidari) manages to make a living for herself. Although her boss is skeptical of her membership in a sect, she acknowledges her will to work, so that she quickly climbs the hierarchy in her establishment, eventually becoming his confidant and right hand. However, as her boss is arrested for sodomy, Tome realizes another opportunity has come, one which could give her the power to become independent of her rural origins.

As with “Pigs and Battleships”, Imamura's semi-documentary approach aims for a reflection of reality while also focusing on the issues defining the world and its people. In the case of “The Insect Woman” the first half shows the life of Tome's family, a tough hand-to-mouth existence which eventually sets the foundation for her desire to leave this reality behind and explore different possibilities. However, urban life is one defined by hierarchies and other structures based on power, reputation and wealth – a logic Tome needs to learn quickly in order to survive, and which sets in motion the change in her persona, making her a stranger to her daughter and her parents. As the lead character, actress Sachiko Hidari gives a believable performance as a woman hardened by her surrounding and experiences, an opportunist by nature whose desire to have a life of her own is presented as part of the zeitgeist.

Additionally, the story of the central character is flanked with events of Japanese history. From the bombing of Nagasaki and Hiroshima to the student protests at the end of the 1950s, the heroine does her best trying to get through, just like her peers and the other people around her. Shohei Imamura's and Keji Hasabe's script define Tome's story as one which is a reflection of the times, an initiation in a way, which is founded in “worker bee”-mentality in the name of an ideology of the self. As with his other features, Imamura seems skeptical about the road where this mentality is leading to, as it also defines the perfect subject, one willing to follow and obey.

“The Insect Woman” is a though provoking drama about “worker bee”-mentality and a pessimistic portrayal of post-war Japan. Shohei Imamura's feature is of timeless importance, especially in a society which is becoming increasingly conformist, suspending individual thought if it helps one's ambition and survival.