Ali Asgari started studying film directing when he moved to Italy, with experience already gathered in the field as an assistant producer and assistant director in Iran. He made his first short film “Tonight Is Not a Good Night For Dying” (2011) as a freshman, and stayed faithfull to the short format ever since. “Until Tomorrow“, his sophomore feature length drama that has just screened in Berlinale's Panorama section, was also supposed to be a short drama, but the topic was of such importance for the Iranian director that he felt the urge to tell the story in more detail.

In the script co-written with Alireza Khatami, Asgari shows one afternoon in the life of a single mother Fereshteh (played by the fantastic Sadaf Asgari) who, after her parents announce their sudden arrival to Tehran, is frantically looking for a sleep-over for her out-of-the-wedlock baby daughter just for one night. We sat down for a talk with Asgari in the Berlinale Palast to ask him about his inspiration about the film, how he found his youngest actor and the blessing of having private investors who put trust into an independant filmmaker.

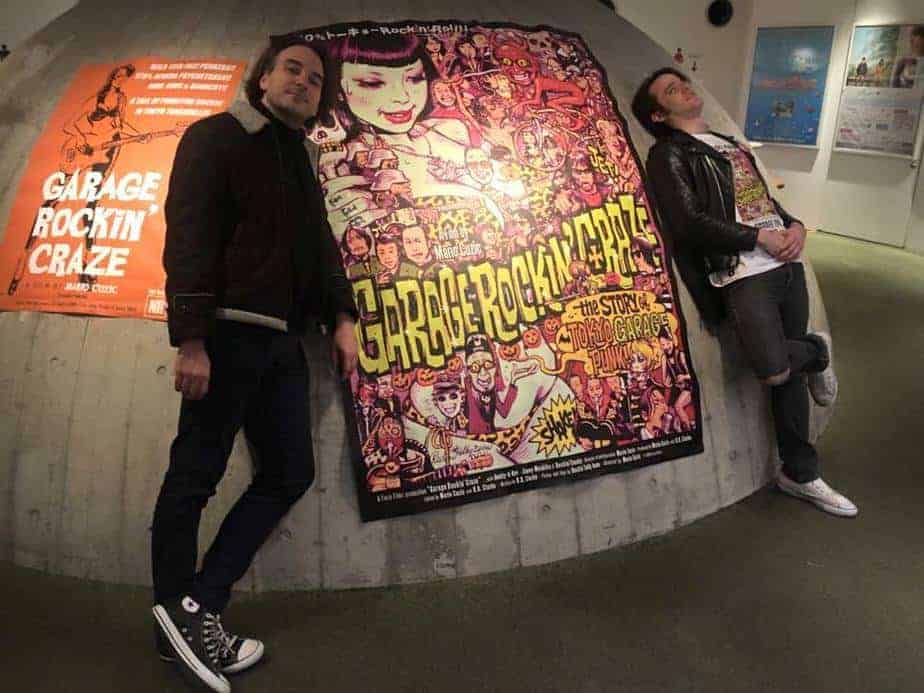

Until Tomorrow screened at Berlin International Film Festival

Was Sadaf Asgari your first choice when you wrote the role of Fereshteh?

In fact, she had the first ever role in my film “Disappearance” which competed in the Orizzonti section of the Venice Film Festival. I was looking for an actress for the film and I had a casting with around a hundred girls. At the end, I wasn't that convinced, but I knew that she was attending an acting class, and that she feels pretty comfortable with acting. I asked her if she would come to try on the role and make a tape. That day she came, and we just talked. I was surprised how talented she was. I chose her for “Disappearance” without knowing that she was ideal for the lead. She acted in other films and I was really surprised with the outcome again.

When I was writing the script for “Until Tomorrow”, I was writing for her because I could imagine her in the film. I was doing dialogues and lines thinking of her.

And where did you find such a sweet, silent baby that put up with so much stress?

She, in fact is a “he” who I found on the set. It was a boy and not a girl, and that was very funny for me, but a baby is a baby and the gender doesn't change anything. In fact, we tried to shoot all the baby scenes with a doll because it was impossible to have a one-month-old baby on the set for twenty five days. On top of everything, the weather was very cold. We asked the team if they knew someone who could help us find a baby that was about one month old, and we also had to look into what kind of dolls we had. I spoke to my costume designer about the solutions. On the first day on the set, we shot the first scene with the doll, and I said “this doesn't work”. The actors also didn't have a connection to it. In the next instance, I asked if we could find a baby for a three day shoot. So I asked the parents to come over and I talked to them and managed to convince them. Actually, that baby was the most expensive actor on the set. We promised the parents to be investing in the future of the child, but it was really difficult because the child had to be on the set from morning to evening. His mother was there with us and we had organised a van for her to be with the kid. It was a bit difficult, but at the end everything turned just fine.

You are dealing with a very controversial topic – a child out of wedlock in a conservative society as Iran, so the question that automatically comes to mind is how difficult was it to shoot the film concerning censorship.

It was not easy because we had to present the script to the censorship board, so when my producer first read it, she asked me to alter something because she was sure they wouldn't accept it. I made some small changes and when we started shooting, it was a different story again. At least they let us. This particular subject is very difficult because the goverment, of course, doesn't support such subjects. The process of making the film also wasn't easy because for getting the money you need to compromise about many things, and at the same time, you need to be careful about what you are writing and making the film about. Basically, it is twice as difficult making a ‘normal' film. As I like those kind of stories that come from my background, I am really eager to fight for them.

You developed a short and then you felt that you had to upgrade it tio a feature length movie, which is interesting because you managed to deal with every single topic in the short format so far. Why did you feel the urge to go a step further?

Basically, as I come from a short-film background and I am interested in shorts, I was thinking how would be possible to use the same elements when we want to make a feature. The big challenge of not having more characters and working with a very simple story was making me think about the possibilities of expanding it, and letting the audience watch it without any difficulties. It was a big deal for me. When I tried it with my feature debut, I wasn't very happy with the result so I decided to make another version for my short film. The challenge was very interesting. I think I won't go this path anymore.

You were actually inspired by your friend to develop this story about Fereshteh. Can you tell us something about it?

In the short film, it all starts with a picture that I saw on the streets of Tehran. I was really inspired by it because it showed two grils – one of them sitting and the other one standing. They were smoking and they looked very sad, but I didn't know what their problem was. I was thinking about that picture a lot. And then, while I was talking to a friend who was very young, she told me how much she wanted to have a baby but she couldn't because her parents were very traditional. The thing is, she didn't want to get married. This is why I felt attracted to tell such kind of story as something representing the new Iranian youth. They are restless about everything and they don't care about tradition. They just want to do what they feel like. That was the inspiration coming from my friend. We had a lots of conversations about that topic, and when I spoke to my co-writer about it, she thought it would be very interesting working on that story.

Would it be possible for a single mother to get an apartment in the nowaday Iran?

The thing is, in Iran everything is possible, but you need to know how. The fact is that there are lot of girls who, when they want to get an apartment, and they can't because they are single women – they usually present men on their side, declaring them their husbands. They rent an apartment together and the other one just doesn't live in it. For men is almost the same. So men also bring a sister or another family member, presenting them as their wives. They sign a contract together and at the end they do their things separate ways. So, all is possible.

Does the fim stand a chance of being shown in Iran?

We are trying to make it happen but basically, last week there was the most important film festival in Iran (Fajr) which rejected the film. I think that there will be basically some changes, at least some parts of the film to make it legal. Maybe the main problem is that the girl isn't married. Knowing this, we shot another scene in which the girl is talking to her best friend saying how they were married but got divorced. So, if there are some problems we can show that version.

Can “Until Tomorrow” impact the funding of your next film in some way?

I am not worried about the funding because I have some private investors who are interested in putting money in my films. And I also have my producers outside of Iran. That is why when I write a film, I don't put local fundings into consideration.

What is your biggest wish for this film?

In fact, for me its really important that the fim was made in Iran and it communicates with younger generations. I have lots of nieces like Sadaf, I have six sisters and they all have families. Most of them are from this generation and when I speak to them it's really interesting what they got to say about their own life experiences. And they are all quite different from my generation. Making this film was important to establish that dialogue, not only with them but with their whole generation. Their issues in life and the way of thinking were significant for me in the sense that I wanted to connect with them.

You made a film from a very female perspective.

As I already told you, the reason for that is that I have six sisters and I lived with them my whole life. Knowing their problems with our very traditional angry father, stayed in my subconsience all this time. It was important I grew up with so many women, and to listen what they got to say. Making this film is very much due to that.

Did they watch the film?

Not yet, because it was finalized right before the festival. Maybe when I am back. Sadat's mother is very eager to see it as well.