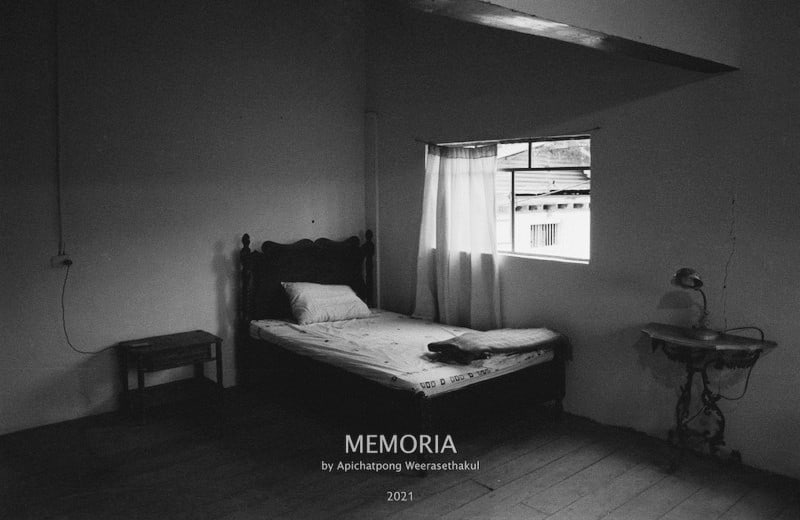

It starts with a ‘bang'. An enigmatic, metallic sound wakes up the protagonist of “Memoria”, Jessica Holland (Tilda Swinton), a Jacques Tourneur-inspired character (“I Walked With a Zombie”, 1943), about whom we don't know much. Aside from visiting her sister, growing orchids, and seemingly being in mourning after her deceased husband, she seems like a mystery we've just witnessed through a sudden awakening. The sensation sets her in motion. She starts to look for its roots, questioning one's sanity, like a detective who's about to lose their senses. Slowly drifting between the worlds of liminal boundaries – between material and imagined, visual and sonic, past and present – Jessica becomes involved in a mystery that will push her closer to the memory of the Colombian past. As it happens with Apichatpong's narratives, the audience is plunged into a journey, too; we're invited to participate and to cherish all of that – memories, sounds and the tactile of the film's layers.

With so many interviews revolving around “Memoria”, I tried to delve into private and intimate realms of filmmaking this time, tackling the side of the movie that comes with the feeling or carnal experience. Apichatpong goes through the blissful privileges of everyday life – sleeping, connecting, listening, remembering – as well as approaching research for “Memoria”, rendering its sonic background and encapsulating death through sound, the collective effort of making the film or tracking Colombian influences for the shape of the film's aesthetics. As always, his words and insight had somewhat of a soothing touch; with a tender voice he went on about his perspective – not only on the film, but more than that, on the human component that builds into artistic ventures.

The interview was conducted by Lukasz Mankowski thanks to the courtesy of the International Film Festival Rotterdam, where Apichatpong was invited for the Encounters initiative, in which filmmakers are paired up with critics, curators or other filmmakers to discuss the condition of cinema in the future.

How are you feeling these days?

I have kind of overflown myself with work because I feel that everybody is planning to open up. And that concerns me as well; I'm also planning for potential promotion trips. With “Memoria” there have been a lot of interviews – I would say this is the film for which I made the most interviews in my career. So that left me without much time for my other works and it's really been different for me this time, as it almost felt like suffocating – I need a lot of time for my artwork, to just think about, and I couldn't focus on it at all. And with “Memoria”, the whole process has been very extended – the film premiered in many countries, one after the other, this country, that country, one interview after the other. So that's where we are. [Laughs]

With so many interviews done already, do you feel you're getting anything out of it for yourself?

Well, because each time I strive to answer with something new, it's been very hard, but you're right – when I try to find a new angle on something, I go through my memory of the experience and I always end up with something new. But thanks to this, I can reflect on the whole process of making “Memoria” as a great privilege and a wonderful adventure, for which I'm very grateful. It's a challenge, though. I'm already looking forward to going out and starting shooting somewhere else again.

In the first dialogue in “Memoria”, one of the first words Jessica (Tilda Swinton) speaks to her sister is soft and blissful: “It's so good to watch you sleep.” Do you happen to watch people sleep these days?

No way, not much. I watch a lot of my dogs sleeping, but I've been on my own for a while now. I missed seeing my partner sleeping, so maybe that was one of my inner desires which eventually found the representation in the script. And I, myself, sleep for only four to five hours a day; my body seems to have adjusted to it, with no need for coffee, not feeling tired. But I'm not sure what exactly it says to me, I really don't know.

In the Fireflies book devoted to the film, there is a letter you wrote as an introduction. There, you tackle the state of mind you were in during the process of filming, going through insomnia, experiencing Colombia, and sharing the ‘bang' with Jessica. The letter is addressed to “Memoria”. Who is “Memoria” to you?

I guess that would be the memories that come with the film. The whole process of filmmaking for me is always a constant dialogue – you engage in the dynamics with so many people and along the way you have so many shared memories of it, with the cinematographer, the sound designer, and the editor. At some point, the film becomes a living entity, you know, an entity you communicate with.

The letter ends with, “perhaps it was another answer”. For you, it's been a cure for the Exploding Head Syndrome the idea for the film started with, as well as the cure for your insomnia. I was wondering if the film after it had been finished and travelled across the world, made you find yourself an answer for anything new in particular?

I think the more you discuss with people about your work – and I've been talking with you before as well – it makes you wash away the doubts about cinema. There's something about making the film communicate in different countries; it seems cinema can go beyond language and connect with people entirely on a universal basis. I think that's been an answer for me – refinding the language of cinema.

I remember that at the beginning of the coronavirus pandemics, you wrote an essay on the state of cinema, titled “The Cinema of Now”. Has anything changed from that time?

I think that the condition of cinema is in a more complex situation than I thought before. We had to foreground a very in-depth debate around it and I think we all struggle to adjust to technology. We strive for creating ways to communicate with people, to reach out in different ways, commercially or not, and I think it's really healthy to talk about freedom. It's essential to establish such dialogue based on diversity; the more we talk about it, it gives us more choices. I'm not entirely sure if it's good or bad, but perhaps just healthy.

“Memoria” is in a way a film about communicating and connecting – this is performed through many layers, one of which is sound. You connect the sound with the earth; the metallic “bang” appearing in the first shot of the film sounds “earthly, like the core of Earth”, as Jessica explains its sonic structure. How did you establish this connection – sound with Earth?

The way I operate is really transparent with each film. It connects with my experience. That is genuinely the feeling I had when I went through the episode of the Exploding Head Syndrome. When you lie there, your head is on the pillow, on the bed, with all the noise in your head, you start to feel that everything's connected – to your body, the floor, the different floors down below, and finally, to Earth. It felt to me that this sound activated the sense of connection – between self and Earth. Essentially, the experience became about self-realization, it came afterwards as an understanding of the peculiar notion, that everyone is connected through different sorts of vibrations. It's not only the planet but the way you talk, the way you move, the way our minds vibrate; everybody is connected and we have really no choice but to be part of this – vibration.

There are so many scenes revolving only about the act of listening: Jessica listening to Hernan's music, where we can only hear a slight change of the weather; Jessica participating in the concert, of which we have no vision at first; Jessica listening to the sounds of the monkeys across the river, which we don't see. These scenes become about participation – and I must say I've never participated in something like this. How did the premise of these scenes appear in your head?

For me, memory is a vehicle for listening and participating, inasmuch as it is a way to experiment with the soundscape of cinema. It comes from me: my own preference of living, my experience, my perspective. When I want to stay focused or when I feel stressed, sound becomes the first sense that I resort to – sound is the first element that comes to my mind. I think that more than visual contact – watching or seeing – it is always the sound that calms me down or makes me focused. It's a very acute notion. And since there is a complicit relationship with Jessica, we have to listen. Maybe in other films, sound is not that important, but for “Memoria” you're superimposed to do so, as it becomes a kind of conditioning for participation. When I first watched “Memoria” after we finished it, I felt that the film made me calm down. The whole process also made me realize I needed to make almost real-life like instructions on how to focus and stop for a moment, and tell yourself – hey, just ‘be'.

I found in your notes that sound is the last sense to go when you die.

This is what Tilda [Swinton] told me, actually. I think during the pre-production, we met from time to time and she was recounting the experience of being with her dad shortly before he passed away. This is when she told me this, “the sound is the last sense we experience”. I didn't think of that this way. But I really hope this is the fact. It was very moving for me, to absorb this information at that particular moment, but also – it was very moving to have this form of a unique collaboration that we established.

And so is the research you've made for the film. Fungi, archaeology, human bones, tired mountain syndrome – it's all very organic. The last time we spoke, you described the process of gathering data as a synchronization – with the information, but also the rhythm, your rhythm and that of the narrative. What made you connect it this way with the research?

I think it's always been a similar process for each of my films. It's about how I gravitate around the topics I'm finding interesting at the time of being. But more so in “Memoria”, because it's concerning Colombia, I felt I was a kid back again. With a completely new and foreign environment, I could explore and through that, I could re-activate my curiosity – about archaeology or infections, but also everything, in general, that is able to give me the spark to move in a certain direction, to different places. So it's also organic in a way, that it was entirely there; it was there to be found and I didn't know what was gonna come up. I just needed to collect all of these.

Was there anything from Colombian art in particular that inspired you in the process of making “Memoria”?

I visited a lot of museums and delved into the local contemporary art scene. The outcome of that research is visible in the gallery scene in “Memoria”, where Jessica stares at some of the paintings. These were made by a Cali-based artist, Ever Astudillo, whose work I incorporated in the film. He passed away a few years ago, but I managed to see his exhibition when I was in Cali. I think it was the pivotal moment to set the tone of the film's image. The mood of “Memoria” starts with Astudillo, as even himself was quite influenced by the ambiguity, shadows, darkness, but also cinema and photography, and mystery in general. And that translated to “Memoria”.

I also found out that you were close with Colombian filmmaker, Luis Ospina. What was his part in making “Memoria”?

We met occasionally and we became friends. I was under the influence of his installation works and I felt that he had this network of filmmakers and still remained independent throughout the years, it felt inspiring. When I was shooting, I would visit the old building of Cinemateca de Bogota, which was built in the 1970s, and then the new facility, back when we screened “Memoria”. And throughout all that time, I felt that Ospina was a huge part of the film. In some sense, he established the culture of filmmaking in Colombia, it's still alive, and vivid, and his spirit – adventurous in many ways – managed to sustain the network of governmental support. He's an icon, without whom it was impossible not to think about when making “Memoria”.

It seems to me that “Memoria” is all about making the journey. It's Jessica's journey, a journey through perspectives, sounds, notions, but then again – it's all yours as it starts from the sound coming from your head. I was wondering have you found anything for yourself in particular through this journey?

It's difficult to answer this one, but I think it's just an accumulation of experiences. Because of COVID, I felt that I don't want to get too carried away by happiness because the pandemics revealed that the world is really a fragile place. Everything with “Memoria” was such a pleasurable thing, I mean, each day was beautiful, but I try not to think of “Memoria” as something that stands out. But then again, I was really dying to go out of Thailand to shoot and this was the moment I learned something about myself – that I thought I would discover something totally life-changing. But I didn't! It's like it's love – when you find something you have just fallen for, and you start to think that this is gonna be the one. After a while, you realize you'll never be able to satisfy yourself unless you stop and feel. It might be the thing that I learned on my own – that I don't need to look out so much, but instead, start to be here, in the present; I don't need to look so much for something that may be beyond there, because there might be nothing out there.

I remember that the last time we spoke, you described Jessica as a microphone – that receives the sounds and transmits them further. Were you able to notice something about the sound on your own during making “Memoria”? Have you heard anything new?

I think physically I got worse because when you get older, the range of frequency that you're able to detect gradually becomes narrower. This might be a good thing, in fact, as it might make you only focus. But it just feels very nice to be able to work on sound – my next project also comes from sound, so I'm really curious what it's gonna turn out, as there is a vast margin to do with sound.