The article was initially published on Sirp

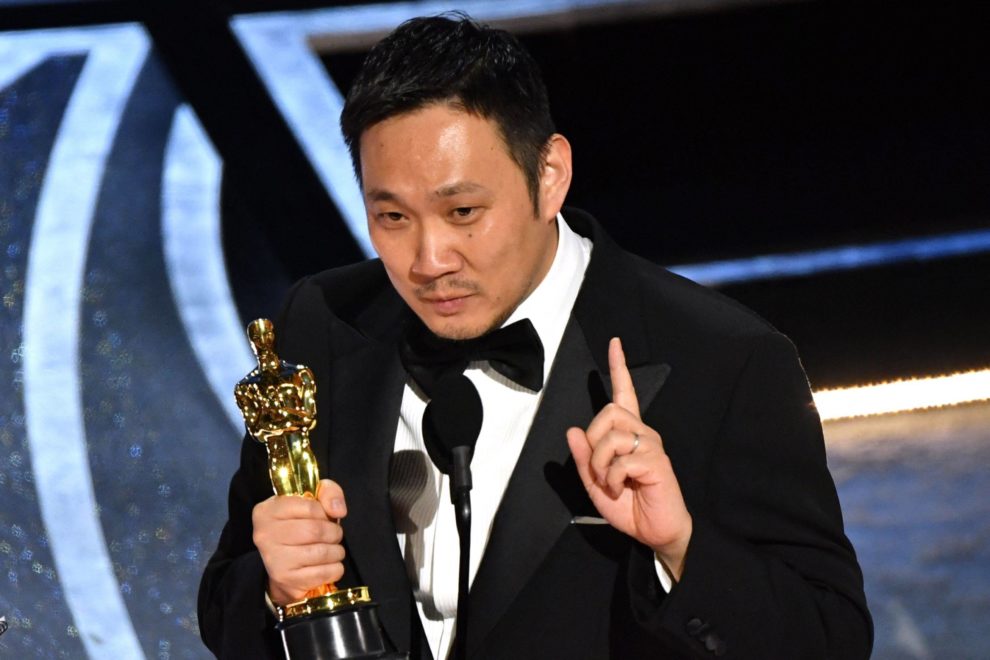

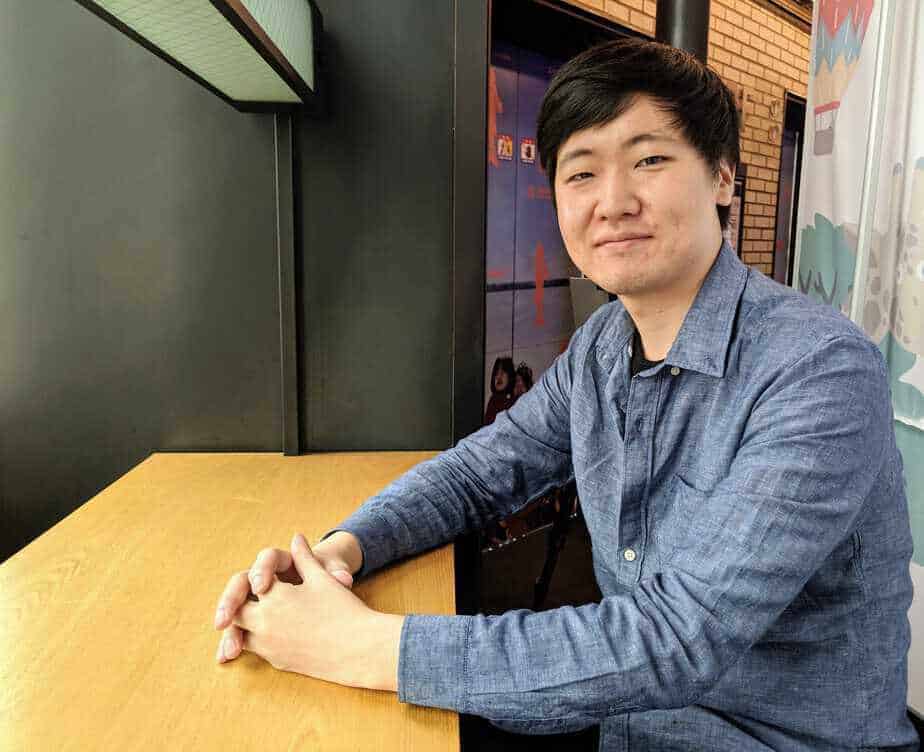

As probably everyone knows by now, the Oscar for Best International Feature Film was given to another East Asian movie on March 27,2022 , after the unprecedented success “Parasite” had two years ago, with the statue going to the Japanese “Drive My Car” by Ryusuke Hamaguchi. Before that, however, the film has also won three awards in Cannes (Best Screenplay, Fipresci and Prize of the Ecumenical Jury), Best International Film in the Independent Spirit Awards, BAFTA and Golden Globes, 9 awards from the Japanese Academy (including Picture, Director, Screenplay and Lead Actor for Hidetoshi NIshijima) and a huge number of awards from Critics Circles and Societies all over the world. In that regard, it would be interesting to give a more thorough look to this success, but also to highlight an issue that has been tormenting Asian cinema representation outside of the continent, and was, in the case of “Drive my Car”, one of the major factors that led to all these accolades.

For starters, I have to state that my personal take on the success of “Drive My Car”, as much as of “Parasite” , is that both were the result of intricate ‘game plans' that aimed in achieving exactly what the two achieved in the end. The producers and filmmakers of the Korean film reached their unprecedented success by appealing to a wider audience, beyond the critics and festival goers, by presenting a title that is visually impressive (a must for mainstream audiences nowadays, to say the least) but also including social commentary that anybody could understand, even if they knew nothing about Korean society. This approach allowed the film to attract both the art house audience but also the mainstream one. Hamaguchi and the group behind “Drive My Car” however, found similar success by appealing mostly to the critics and the festival circuit, which essentially comprises of the major ones in Europe (Cannes, Venice, Berlin, Rotterdam etc) and the people who attend or follow them, with the bulk of all the aforementioned essentially being what we call ‘art-house audience'.

At this point, allow me to explain the differences between the concepts of the mainstream and art-house audience, even with a bit of generalization. The former cinemagoers primarily watch movies to have fun, enjoy the spectacle if you prefer, which is why action, comedies and romances are so popular. In that regard, movies that are fast-paced, visually impressive (meaning including much SFX) and do not demand particular contemplating about what is happening on screen, dominate this category. The art house audiences on the other hand, prefer their movies to unfold almost exactly in the opposite style, with the slow pace, the intense commentary that leads to further contemplation and the overall immersion to the cinematic beauty of the movie being their main preferences. Also of note here is that mainstream movies are mostly exhibited through distribution in theaters, while the art house ones find their main outlet to be mostly festivals. This does not mean that one forbids the other (of mainstream films screening in festivals as we have seen extensively lately in Cannes or art house films finding extensive distribution), but as a general rule, this is the case.

To go a step further, the whole concept of ‘art-house cinema' seems to be dictated by four different schools: the French New Wave, the Italian Neorealism, the German Impressionism, and the Soviet Montage Theory, with the first one being the most dominant. Evidently, the styles and techniques that derived from these four movements have developed and changed significantly through the years, but the fact remains that the particular kind of cinema is still dominated by these movements, maybe with the adding of an experimentation that frequently derives from conceptual artists that turn filmmakers. As such, identifying European cinema with art house cinema is the prevalent tendency among the particular audiences, and one that happens even unconsciously on occasion.

Conjuctively, and since their audiences comprise mostly of art-house buffs, the particular style is what dominates the programs of both the major festivals and the smaller ones, which, truth be told, frequently follow the bigger ones as closely as possible. This tendency, of preferring films that follow a more or less particular path, also extends, unfortunately in my opinion, to the representation of Asian cinema in the specific circuit, with the overwhelming majority of the movies from the region selected following the standards of the European style. Even more so, this tendency extends to context and not just style. For that, however, I will just let Mattie Do, a Laotian filmmaker who mostly directs horror films, and whose latest, “The Long Walk” has recently found distribution in North America, speak: When you make a film from one of these developing countries that no one's ever heard of and when you're the first woman who's ever done it, there's an expectation of what the film should be. And that expectation is it should be poor people, groveling and suffering, long suffering. It should be poverty porn. I once said to someone, “Why do we always have to do that? Why is that the genre for us? Why is it documentary, like we're an anthropological study or some sh*t? Why does it have to be this arthouse movie where some Asian mystic person sits for 10 minutes in the ugliest wide shot possible just staring at the wind, experiencing the world on a different Asian mystic level than white people could possibly hope to understand?” No. Like, f*** that sh*t. Those are boring films and, if everyone's doing that just to get into the festival, then the festivals aren't doing their job to try and find and discover new stories and new potential, new possibility… (excerpt from the filmmaker's interview at slashfilm.com

The particular issue is also intensified by another aspect, the whole concept of co-productions. European festivals receive funding (occasionally their most significant source of income) from the European Union, which demands, though, a certain number of European Union films to be part of the program, essentially the majority of films picked. Considering that festivals also highlight their diversity by bringing titles from the American continent, and that, after Brexit, movies from the UK do not ‘count' as European, the space left for Asian movies is truly miniscule. There is a window, however, and that is that Asian co-productions with European countries do count as European Union titles, which allows festivals to pick more easily from that pool. At the same time, however, and as Teresa Kwong, director of Hong Kong Arts Centre and long time producer, mentions in an interview at Asian Movie Pulse (https://asianmoviepulse.com/2021/12/interview-with-teresa-kwong/), some of the requirements of co-productions include having post-production done in the European country that provides the additional funding, and paying the taxes for the European professionals working in the movie. These requirements, apart from cutting the funding of the movie almost 50%, inevitably result in Asian movies having an intense European “flavor”, deriving from the collaboration with film crews from the continent. This tendency also takes place in movies that are not co-productions, but still include European crews, as, for example, in the case of the Tiger Award in Rotterdam, “The Cloud in her Room”, which features Belgian Matthias Delvaux as DP, and has a rather distinct European cinema flavor.

This tendency, of festivals picking Asian movies that follow the aforementioned path, also has an antithetical repercussion. As Fahmidul Haq, visiting professor of film and media at Bard College, USA, writes in his book, “Cinema of Bangladesh: A Brief History”: The drawback of taking foreign funds and entering the global distributing markets is a kind of self-censorship by filmmakers and a tendency towards selecting the kind of scripts that might be favored by the financers. This invites risks in representing Bangladeshi culture and society as an ‘exotic commodity' to the Western audience. Theorists (Chow, 1995; RAju, 2015) called it as ‘the Oriental's orientalism' an idea that was generated from the original works by Edward Said (1978)… In many art house films made in the Third World, poverty is represented as a commodity for Western audiences. The challenge is how an independent filmmaker can protect themselves from this clout and create his/her space in global cinema at the same time. Evidently, his remarks mirror the aforementioned by Mattie Do.

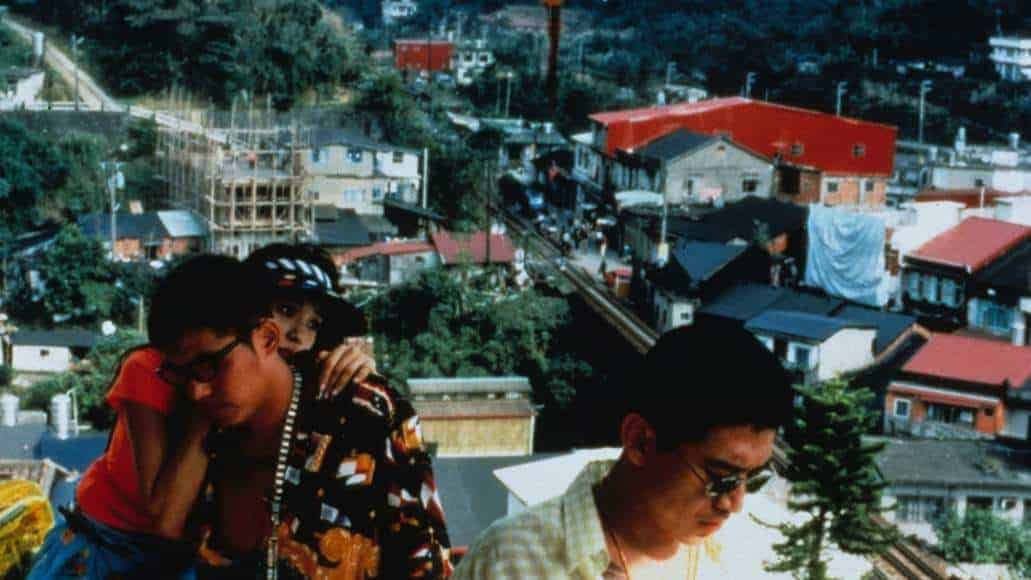

To come back to the initial point about “Drive My Car”, Hamaguchi's movie “exploited” all the aforementioned notions in order to succeed, particularly because the film is as much Japanese as it is European in its context and general style and aesthetics. The protagonists are driving a Saab for example, the director is staging a European play (Anton Chekhov's “Uncle Vanya”) and there are also a number of scenes, most of all the one where the protagonists put their hands above the top of the car holding cigarettes while Misaki is driving, which exhibits a rather obvious French-cinema essence. Even more evidently, the title of the movie is a direct reference to the homonymous song by the Beatles, which the director wanted to incorporate in the movie, but had trouble getting it. Of course, the movie does not qualify at all for the “misery porn” category, but at the same time, the protagonists are rather unhappy and remain so for the majority of the movie, despite the quite hopeful finale.

Furthermore, the movie also includes a number of elements that could be counted among the concepts (European) film festivals promote, with the inclusion of a mute actress (disabilities), Korean and Taiwanese actors, both in the film and in real-life, (minorities/immigration and anti-racism) and an overall message that art can overcome any kind of language barrier. At the same time, the inclusion of one of US audience all-time favorite elements, that of the road movie, allowed Hamaguchi to reach the American art-house audience also, as the fact that “Drive My Car” became the first non-English-language film to win Best Picture from all three major U.S. critics groups (the Los Angeles Film Critics Association, the New York Film Critics Circle, and the National Society of Film Critics) eloquently proves. Lastly, basing the story on a series of Haruki Murakami's short stories (“Drive My Car”, “Scheherazade” and “Kino”), an author who is quite popular internationally but has been repeatedly criticized in Japan as “Un-japanese” and “too American-like” also adds to this duality of the movie (https://www.theguardian.com/books/2018/oct/11/haruki-murakami-interview-killing-commendatore) , (https://www.theguardian.com/books/2014/sep/13/haruki-murakami-interview-colorless-tsukur-tazaki-and-his-years-of-pilgrimage)

All the aforementioned do not mean that Asian films that follow this European path, and even more so, the masterful “Drive My Car” are not great films. At the same time, however, they continue a trend that as Mattie Do and Fahmidul Haq mention, have strangled the creativity of Asian filmmakers, at least the ones who aim at promoting their work through the festival circuit, while forbidding the audience to see Asian people as they are in reality, and not as exoticised, usually unhappy or poor versions of themselves.