11. Leila’s Brothers (2022) by Saeed Roustayi

A sister and three brothers are all in their 40s. It’s time to change their fate and financial situation. They have a plan, but it will only work if their father sticks to it too. There is not a minute of the nearly three hours long family epic that is too much. Its strengths are the dense script and the outstanding acting performances of the entire cast. By taking the example of a particular family, Saaed Roustaee manages to present a strong and impressive social critique. (Teresa Vena)

12. No Choice (2020) by Reza Dormishian

Dormishian makes a number of social comments in his movie, with the situation of the homeless people in Tehran and the lack of will of the government to help them, the place of women in Iranian society, the ways the police works, and the concept of crime and punishment being in the front line. At the same time, however, all these are inevitably placed in the background, as the focus shifts on the fight between two powerful women, who are also activists even if in different ways. This aspect, that both want to help but eventually find themselves clashing, is the most intriguing in the narrative, even more so since Dormishian highlights the fact that both are lonely, due to their will to help others. This element also benefits the most by the acting of the two women, with Fatemeh Motamed-Arya as the doctor and Negar Javaherian as the lawyer giving truly outstanding performances, with their antithetical chemistry (the former acts more with her facial expressions while the latter is more vocal) working excellently throughout the movie. (Panos Kotzathanasis)

13. No Date, No Signature (2017) by Vahid Jalilvand

A pathologist is involved in a traffic accident. In order not to have to deal with the police, he suggests that the child of the family who was in the other car should go to his clinic to be examined. The family withdraws at the last moment. The next day, the boy’s body lies on his table. Director Vahid Jalilvand masterfully stages this thriller, which only develops its drama because the protagonists have no trust in the country’s justice system and are afraid to confront patriarchal traditions. (Teresa Vena)

14. Oblivion Verses (2017) by Alireza Khatami

Alireza Khatamati directs a very rich film, both in context and in visuals. His critique is obviously directed towards totalitarian regimes, with the overall climate of fear that surrounds the story pointing directly to the eras of Pinochet and Franco. Khatami seems to state that one of the purposes of these kinds of regimes is to implement oblivion, not to allow people neither to know nor to remember their despicable practices. The fact that the protagonist’s only major trait is his uncanny memory works wonders for this particular comment, as it places him directly against the authorities, and the overall narrative in terms of entertainment, since it gives the man an almost super-hero hypostasis, which is actually stressed as the story progresses (although in realistic terms). (Panos Kotzathanasis)

15. Pari (2020) by Siamak Etemadi

What is unique in the film is Pari’s perspective itself, a perspective of a foreigner in a strange land whose culture she does not know, a perspective of a woman from a certain culture that demands some kind of passivity and, above all, a perspective of a mother who wants to make up to her son for not giving an effort to get to know him, but rather trying to mould him to fit some ideal image. Envisioned by Siamak Etemadi, who has been based in Greece for the last two decades, the image we get is layered and respectful to both cultures, while also highlighting their differences and incompatibilities. (Marko Stojiljković)

16. Radio Dreams (2016) by Babak Jalali

A dissident writer in his old homeland of Iran is relegated to the role of a radio journalist at the Farsi-language station somewhere in Bay Area in California. But he has a dream to organize a joint gig of Metallica and the rock band Kabul Dreams from Afghanistan, which is not an easy task since the station is run by an array of editors and managers who all pull in their own directions. Partly a mockumentary, partly a deadpan absurdist comedy and partly a serious drama about emigration, immigration and the place of art and philosophy in a utilitarian world, this smart and gentle movie directed by the British-Iranian filmmaker Babak Jalali is a significant contribution to the emerging genre of Irano-Americana that offers a holistic insight into the topic of the Iranian diaspora stretched between the worlds

17. Taxi-Teheran (2015) by Jafar Panahi

Yet another not-a-movie of the recognized director Jafar Panahi, who clashed with the Iranian government with subjects of his works and has been serving his 20-year ban on directing movies or writing screenplays. Taxi-Teheran pretends to be a documentary, in which Panahi, showing himself in a camera, poses as a taxi driver and takes various passengers on free rides. Through their stories and dialogues, the director shows a microcosm of modern Iran, with its absurdity, horror, but also beauty. And of course, he gives a masterclass in mocking the censors. (Joanna Konczak)

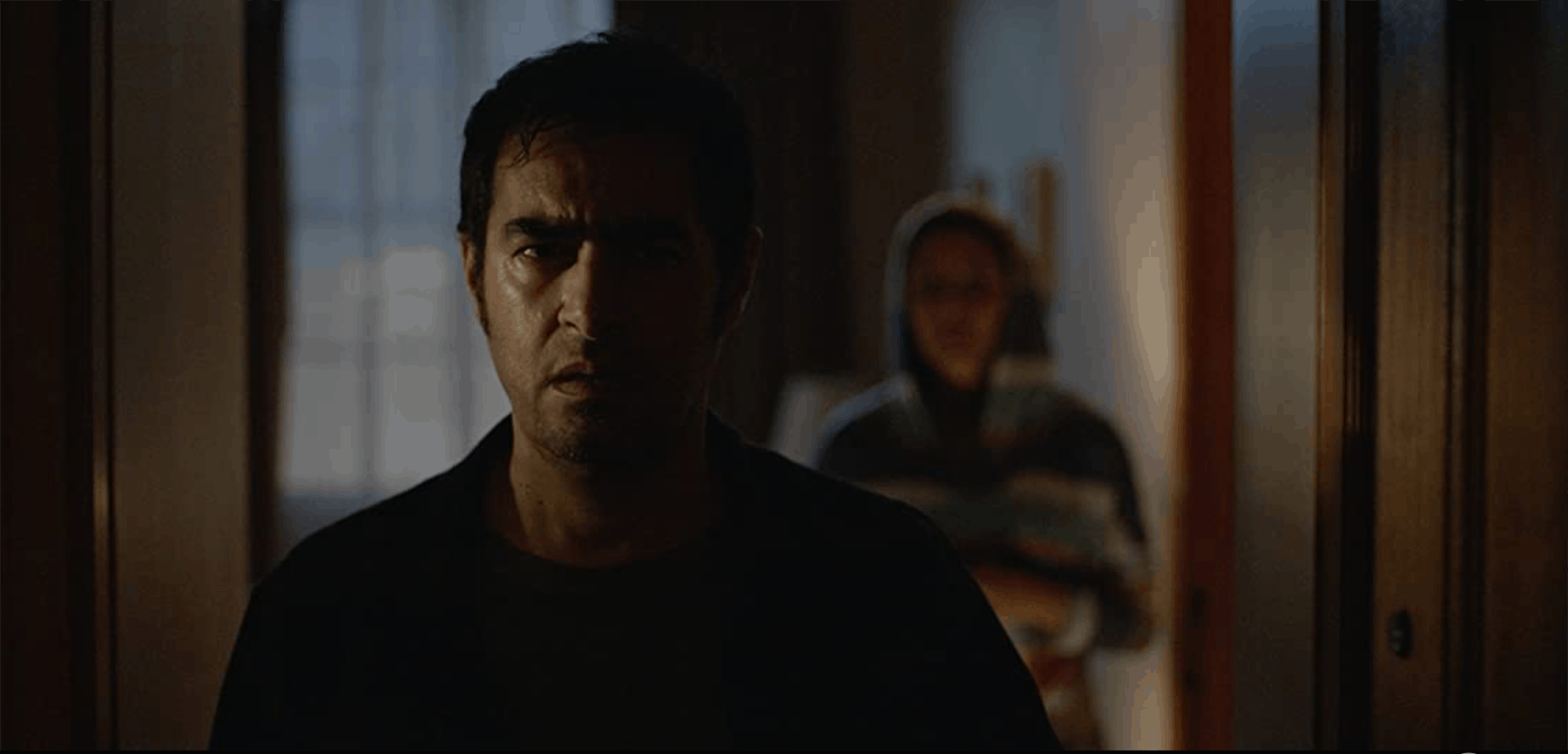

18. The Night (2020) by Kourosh Ahari

“The Night” starts as an ordinary haunted house (hotel) ghostly tale, but thanks to the clever script (by Milad Jarmooz and director Kourosh Ahari) it slowly turns into an allegoric descent into the mind of a tormented man whose inability to face his own demons and mistakes is finally catching up with him. There are some casually disseminated clues in excerpts of conversation, and they gradually come together at the end, but the film never climaxes with a big reveal or a pedantic explanation. Instead, after placing the seeds of fear and discomfort, it makes them develop and leaves space for the audience to reflect. One of the film’s subtle assets is the way it creates a growing tension with no use of cheap tricks. The foreboding aura starts to form at the very beginning, with Babak in front of the mirror, his throbbing toothache and with an enigmatic hint delivered by Babak’s doctor friend after dinner. It then fully develops in the ghostly Hotel Normandie that quickly turns from benign shelter into the quicksand of his conscience. (Adriana Rosati)

19. The Slaughterhouse (2020) by Abbas Amini

Considering Amini’s aforementioned statement regarding his feature, the image of the slaughterhouse constitutes the symbolic framework of the story, a fitting metaphor for the world the film presents. Right from the start, especially upon observing him dealing with the situation, you might guess Motevalli is not as innocent as he may seem, since his repetitive assertions about the security system not working properly and his demand to fix the situation are, all in all, quite transparent. In the end, perhaps the question about who the perpetrator might be is not as interesting as the world or rather the system which allows them to act a certain way, and which makes people like Amir and Abed follow their orders, no matter how immoral or questionable they may be. (Rouven Linnarz)

20. The Warden (2019) by Nima Javidi

With its strong allegoric clues, “The Warden” suggests a reflection about some major issues like the capital punishment and the abuse of authority but it is not deeply assertive in doing so and the movie can be simply read as the crisis of a man out of his comfort zone. Jahed sees his familiar environment suddenly becoming alien and turning against him; once the puppet master, he is now trapped like one of his inmates. But the Major – whose rigid professionalism has made him emotionally unavailable – will also rediscover his human side along the way, challenged by his alter ego, the feminine character, all-round instinct and pathos, Miss Karimi. (Adriana Rosati)