translation by Lukasz Mankowski

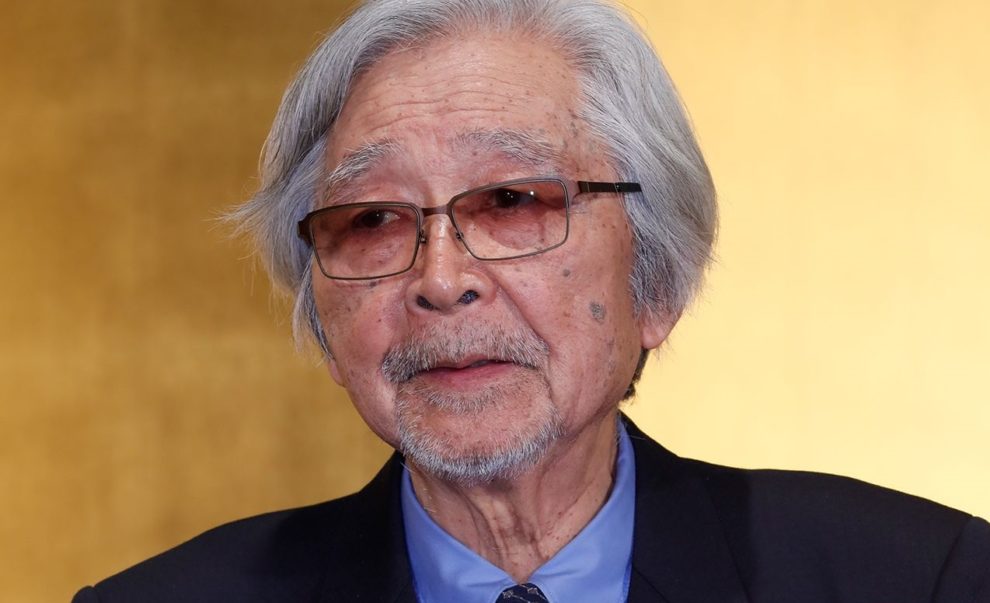

Yoji Yamada is a Japanese film director most known for his Tora-san series consisting of 50 films shot over 25 years, making it the longest theatrical film series. Yamada made his directorial debut in 1961, and has since won the Japanese Academy Award for Best Picture four times, and has been nominated for dozens of other awards and honours at festivals worldwide. In 2019, more than two decades later, Yamada returned to the series with “Tora-san, Wish You Were Here” (2019).

On the occasion of “It's a Flickering Life” screening at Toronto Japanese Film Festival, we speak with him about adapting Maha Harada's novel, the Japanese studio system of the past and the differences with the current situation, Masaki Suda and Kenji Sawada, and nostalgia

“It's a Flickering Life”screened at Toronto Japanese Film Festival

Why did you decide to adapt “Kinema no Kamisama” by popular multiple prize-winning novelist Maha Harada and how close to the circumstances of cinema at the time is the story presented in the movie?

Since the 1950s, throughout the 60s, Japanese Cinema truly experienced its peak. It was a fulfilling period. At that time, we produced many films that were discussed globally. Back then, I was in my adolescent years, but in terms of the producing model, it was still the studio system. Japanese film companies formed a distribution network, they had their own theaters and shooting studios. Therefore, they could shoot and show their work at their own place and distribute it the way they wanted. It happened that I paved my way to the world of film exactly in the time when Japanese Cinema experienced its golden era during the studio system period.

At the Shochiku studio, the name to reckon with, a true maestro, was Yasujiro Ozu. He managed to influence a number of people working underneath him and left a huge impact in the industry in general, as many generations simply wanted to start making films. Among them, there was me – I also learned my craft at Shochiku. This time still brings the feelings of nostalgia.

Right now, Japanese film industry goes through a difficult time – we're weak. Everybody in the world recognize that – where did the old good Japanese films go to? I think of these times with a feeling of yearning – I miss the times when we could say that Japanese films are powerful. That's why I started to think whether I could make a film that would recall this wonderful period. Out of chance, I came across the novel – a story of an old man looking back to his youth days – and decided that, through this formula, I want to reconnect with the old times I really miss. That became the main motif of the film. My main message was to say that we had the chance to experience such beautiful times.

How was your cooperation with Masaki Suda and Kenji Sawada and what are the most important difficulties in having a movie with the same character in two different timelines?

Suda-san is currently the most influential, charismatic and popular star among Japanese actors, meanwhile Sawada-san was the most beautiful actor in Japan during the 40s and 50s – everybody was in love with him. These two playing the same person was a perfect match in terms of casting, an ideal combination.

The film evokes nostalgia quite intensely. How do you accomplish that?

The setting of the film is the cafeteria near the shooting studio [of Shochiku]. Directors and screenwriters gather there to collect and exchange ideas. The fact that such a place exists stands as a proof of how beautifully abundant were the times I decided to depict. Right now, there is no cafe like that. Back then, the studio had their own dining room and coffee shop. People would do talk while enjoying their tea.

Director Tai Kato shot a yakuza film about that. Back then, there was a saying that if the Shochiku setting made it through rain, the rain was mild. In order to have heavy rain, Kato once stopped the whole shooting. The story became a hot topic in the coffee shop the next day. After that, another filmmaker, Hideo Oba said that, ‘The rain of Shochiku is not the downpouring rain. Th Shochiku rain is a drizzling one. Shochiku rain is like a gentle breeze of the wind.' He continued, ‘If you want to show the wind, it's better to do it with Toho and Kurosawa. Shochiku is not concerned with that.' These are my memories of the dynamics we had back then. We all felt we should become like Kurosawa, but for Oba, there was something about the value of rain about which he would talk a lot. There is a reason why such places like this cafeteria exist. It enables all the people from the film world to gather there. Oftentimes there are people who spend their whole lives making films at one studio. And it was a place that I spend my youth at; and it's partially the motif of the film.

What is your opinion of the Japanese movie now, and what are the most significant changes you witnessed in it throughout your career? How do you feel you have changed?

We don't have studios anymore. The finest filmmakers, Ozu and Kurosawa, they made their films within the studio system. Kurosawa himself often expressed his regret about that, too. Toho's studios are still somewhat remaining, but it differs from what they were used to be and the ones that I was working at. These that I recall would abound in so many excellent filmmakers and artisans. It's not about the building – it's the people. As for me, the studio culture in general, I think of wealth of people. Many cinematographers, make-up artists, costume artists, props people – everyone was there. We were all there. That's why I wanted to make a film – to reconnect with such notions.