In Woo Ming Jing's latest feature film “Stone Turtle” which world-premiered in Locarno's International Competition, an immigrant woman takes revenge in her own hands after her tormentor from the past appears to challenge her. It is a feminist tale in which folklore, dance and genre tropes play a significant role in layering the non-linear plot. Parts of the events are getting re-told, re-plotted or even re-dreamt to steer the narrative in other directions. Woo makes no secret of his biggest influence – Harold Ramis' “Groundhog Day” (1993), and even the Netflix series “Russian Doll” which is given in the repetitiveness of certain events that get altered by Zahara when she wants to influence the now by changing the past.

“Stone Turtle” screened in Locarno Film Festival

Regarding other filmic influences, they mainly come from Japanese sources, and this is not just the case with the animated part drawn by Paul Williams, an artist who, among others, worked with Studio Ghibli. His drawings are soft, done in pencil and watercolour, and it is here that he is recreating a Testudine yet again, after his work on “The Red Turtle” for Ghibli in 2016. The old folktale comes to life in this part of the movie, connecting the legend with the action-packed events.

It is important to mention that Woo had also made a hidden hommage to Hiroshi Teshigahara's film “Woman in the Dunes” (1964) given in the introductory dialogue exchanged between Zahara and a man called Samad (Bront Palarae), an island intruder who claims to be a turtle researcher on the quest to find a rare species. Right after his arrival when all of a sudden the boat which brought him disappears, there is a hint at something cooking up. Samad's rough physique is squeezed in a suit, and his search for ‘eggs' looks more like tracing human footprints.

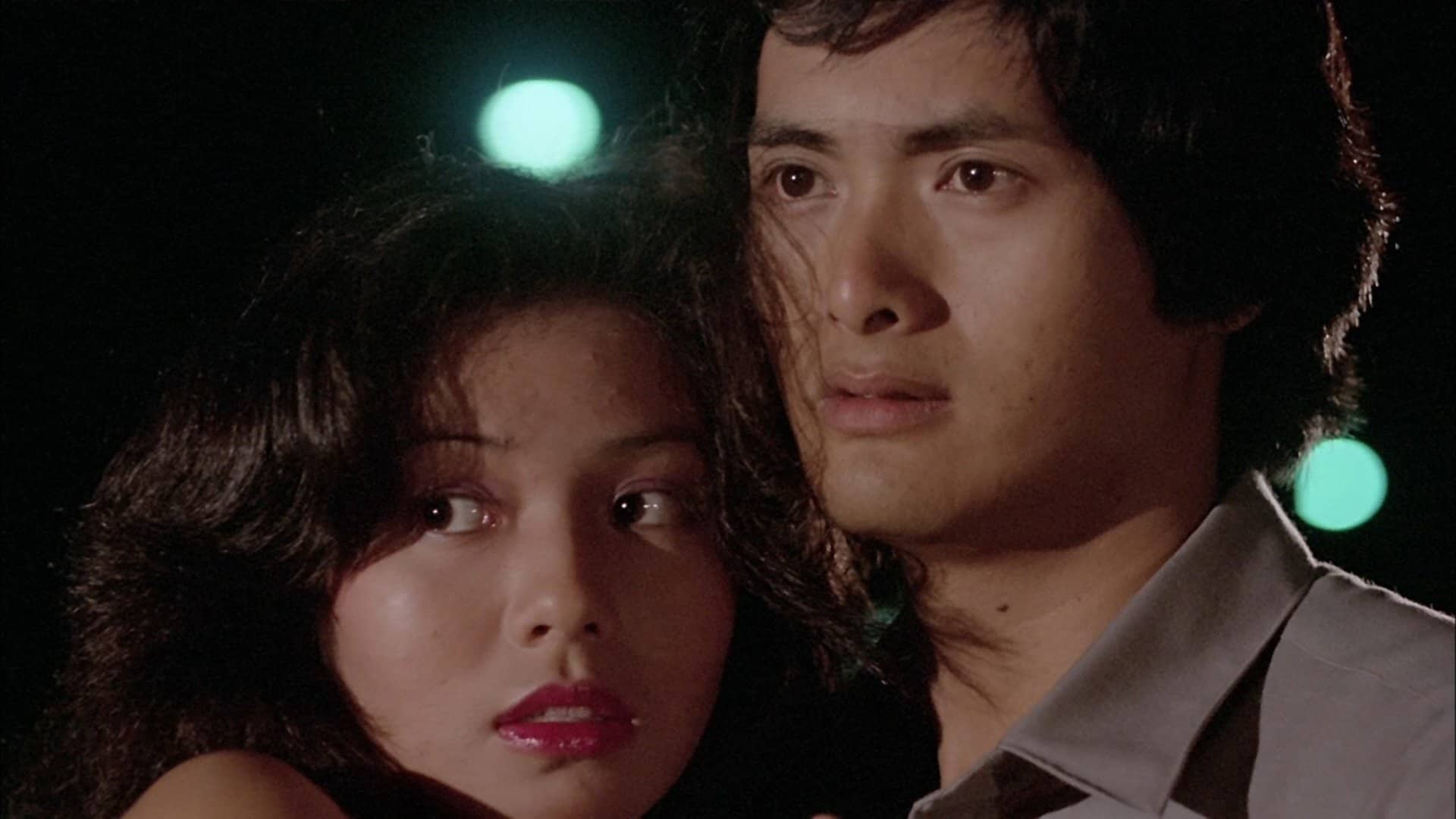

Upon his arrival, the isolated Malaysian island becomes a place of the merciless cat and mouse game under the wake eyes of ghosts who have two things in common: being women, and former illegal immigrants. In this secluded, until that moment seemingly peaceful site, sans-papiers lived in harmony with the only two living beings that roam the area, and who come around by selling turtle eggs on the mainland's black markets; Zahara (Aasmara Abigail) and her 10-year-old niece Nika (Samara Kenzo) escaped their native Indonesia after the girl's mother was murdered by the family for staining their honor by giving birth to a child out of wedlock. They are, in a way, as invisible for the outside world as their hosts.

The above-mentioned scene, some five minutes into the film, is one of the most brutal: we see the ritual in which Nika's mother is killed by heavy stone blows to her head, but there is much more to this shocker than just a merciless execution. This particular moment feels like a strange body in the story, until the proper family secret gets revealed.

“Stone Turtle” doesn't lack in violence, and the soft, natural light the cinematographer Kong Pahurak (also behind the camera in Woo's “Second Life of Thieves”, 2014) used for shooting most of the film's scenes, turns the color of blood as vintage as Zahara's red dress. The clash between the bad guy and good girl turn bad has its twists and turns, and despite of a river of blood coming from a series of despicable murders, there is also a small nod to silliness in representation of mercenaries à la Takashi Miike when three men appear at the beach armed with different types of cold weapons, one more useless than the other.

There is much more to the film than a tale of revenge and regret. Deep inside it is also a political commentary on the Malaysian immigrant policy. Nika is not allowed to school as a non-citizen, and the ghost of a murdered Chinese woman has a terrible tale or two to tell.

Asmara Abigail and Bront Palarae are not for the first time on the screen together. They could be seen in Joko Anwar's “Gundala” (2019) and in his this year's title “Satan's Slave: Communion”. Both give memorable performances as people driven by revenge, each for their own reasons.