Ken Kwek's newest feature “#LookAtMe” tells the story of Singaporean YouTuber Sean Marzuki (played by yao) who is prosecuted and jailed after uploading a video in which he makes fun of a homophobic megachurch pastor for a sermon demonizing gay people like Sean's twin, Ricky (played also by yao). A visceral experience like few others, the movie takes the viewers on a rollercoaster ride through different emotions and genre influences.

On the occasion of “#LookAtMe” premiering at the New York Asian Film Festival, we talk with director Ken Kwek, producer and actress Pam Oei, and actor yao.

“#LookAtMe” is screening on New York Asian Film Festival

First, congratulations on the movie finally premiering. Can you please tell us how the movie was received?

Pam Oei: We've waited a long time to meet an audience and when we finally did, it was a relief. It was very nice to hear the audience's reaction – they clapped a lot, they laughed a lot, they were in awe a lot.

Ken Kwek: It was very satisfying to finally put the film up in a crowded cinema. There were a lot of cheers and laughter during the first chapter, and then in the middle section, when things took a turn and the tone shifted, everyone was deadly quiet. It was great to see that the shifts in genre worked. New Yorkers got it, allowed themselves to enjoy it.

yao: I was very gratified, getting to see all of our hard work after three years – seven years for Ken. As an experience, the movie is relentless. I didn't think that's what it would be. On the page, it reads quite like a play, with a lot of dialogue. But getting to see how the page goes to the screen… They say you make the movie three times, right. And when Ken made the movie the third time, it was something special.

yao mentioned that it took seven years to make the movie. Can you speak a little bit about the process? What compelled you to tell this story?

Ken: I started writing the film seven years ago and over time, several things inspired me. A number of activists, lawyers and artists were being charged or imprisoned in Singapore for seemingly minor infringements. Two religious leaders were jailed for corruption, including a pastor who misappropriated 50 million dollars of his own church's funds. I would say the first inspiration came in 2015, when a 16-year-old Youtuber was arrested and jailed for dropping a video in which he went on a rant against Christianity and upset a lot of people.

That video was frankly stupid and nonsensical, but it got me thinking: what if this YouTuber actually had something meaningful to say? What if he's crude and rude, puts things in a foolish and offensive way, but his message is ultimately a sympathetic one? What if he was doing it to defend his family? That's how the character of Sean Marzuki was born. He drops a video and, as a Youtuber, of course he wants a million likes and subscribes. But ultimately his offensivenes is underpinned by a very fierce love for his gay twin. So the film is inspired by different real-life events, but I distilled it all and turned it into the story of one family's experience of homophobia on a state and societal level. It was a difficult film to make.

Pam: Yes, I cannot tell you how improbable it is for a film like this to come out of Singapore. It took a lot of time to raise the funds.

Did you experience any other setbacks apart from raising the budget?

Pam: Getting permits for locations was hell, Singapore is not very supportive of indie filmmaking that way. The shoot was tough, wanting to pull off the scale of production that Ken envisioned with the budget we had. And then, after we finished shooting the film and Ken was in post-production, COVID happened, and everything came to a standstill.

Ken: Yeah, a lot of festivals were canceled in 2020, so we had to postpone the film's release for quite a while. Some festivals returned with hybrid models in 2021, but we didn't want an audience's first viewing of the film to be online. I feel this is a very visceral film which needs to be experienced on the big screen. I wanted to do justice to the film and our producer, Jeremy Chua, did too, so we held out and waited until now to release it at the New York Asian Film Festival.

Did you experience any setbacks for example from religious groups? Because a big part of the movie criticizes some aspects of organized religion, the hypocrisy behind it.

Ken: I didn't set out to criticize religion as a whole, I set out to depict a particular strand of religious fundamentalism. In terms of whether there was any pushback on the ground? Nobody knew we were making this film. We had to be quite careful about how we executed it. It was difficult to get permits, but Pam did a lot of pushing, as did Jeremy, to get us locations. It was a big operation, but we had to be as discreet as possible. Nobody has seen the film or known much about it until now.

What are your expectations about the reception in Singapore?

Ken: Frankly, I don't know what to expect. But I couldn't have planned the timeliness of the film's release.

Pam: The public debate over Section 377A and LGBTQ rights has been reignited in Singapore, which we couldn't have known would happen. I mean, all within two weeks of the release of the film at NYAFF.

Ken: Real life events that cut to the heart of what this movie is about are happening as we speak. So now the film has a very pointed relevance and some people will inevitably view it as social commentary. But I see it primarily as the story of one family – their journey from a state of innocence to going out into the world, and facing the hatred and pressure that wider society puts on them. I wanted to show these pressures in a heightened cinematic form. Meaning, I wanted create something which is visually bold, expresses different tones and blends genres in an unexpected way. In New York, the audience stuck with me, stuck with the story. I was glad to see that after we transition from a family comedy to something deeper and darker, the audience was still interested. They went along with the ride. In Singapore, I don't know.

yao: We witness the radicalization of Sean Marzuki in the second part of the film. But hearing the audience's response was a relief, because it showed they hadn't turned cynical. They still believed in the heart and soul of this boy. They wanted him to stay untarnished. They wanted him to continue to retain some of his humanity. That was something I didn't expect. I thought this would split people. Some people might say that violence is the only answer to hatred, and some in the audience might have thought so. But most didn't. That was a beautiful reminder that the story really is about a family and this individual's humanity. Of course, it's also about larger issues, but people are still following this specific family's journey and are invested in it.

It's so easy to end it on a dark note, but not losing himself, his human nature, is the ultimate win for him.

Ken: He's a character who starts as an innocent, lovable teenager. He's a YouTuber, so he wants to be followed and liked and have a fanbase. By the end of the film, he's a dark avenger. The challenge is in reminding the audience that deep down inside, he never stopped being that funny, mischievous boy.

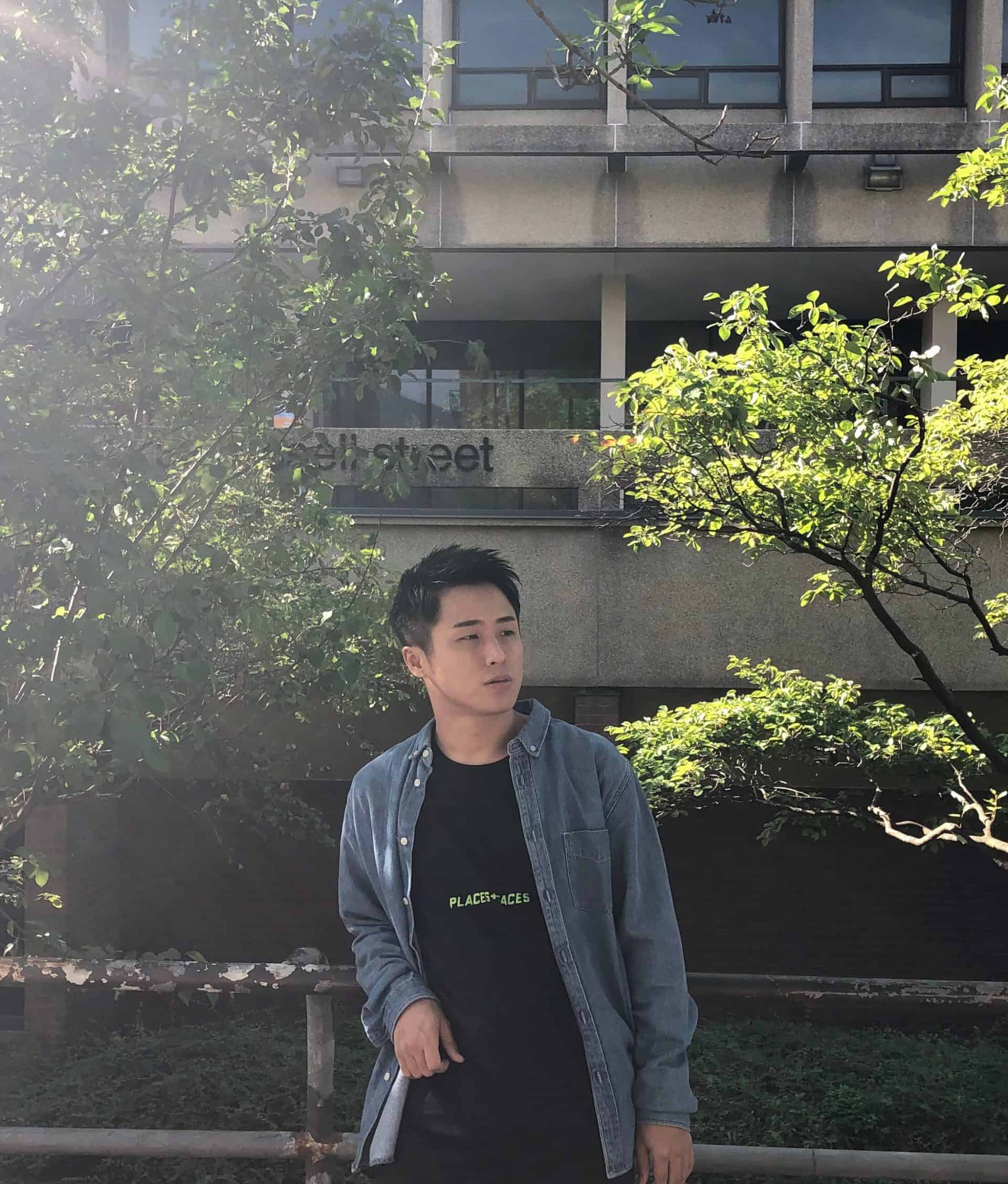

yao, you play twin brothers Sean and Ricky Marzuki. Can you tell us a bit more about the characters? How did you approach them?

yao: The original character for Sean was created by Shane Mardjuki and Ken. They did a series of improvs around the character in 2015. Shane was my body double for Ricky and Sean in the film. We got matching haircuts, and we would memorize the scenes and work on them together.

Performance-wise, I was acting with a brother. Shane really had the lion's share of the work developing the character of Sean. It was just a matter of taking the reins from him and experimenting with my performative sensibilities. Ricky, on the other hand, was more of a listening journey, because he's a lot more intuitive, patient, and quiet. It was about exploring dualism. I'd be like “Ok, what would Ricky do in this situation, what would Sean do in this [same] situation?”

Once I spent around an hour working out their signatures. For me, it was easier to get into the characters if I had the image of their signatures in mind. Ricky's was more flowing, had a more cursive influence. Whereas Sean's looked like a jagged scribble. It was fast and it was messy, and you almost couldn't see all the letters because they were scrunched up together. That was part of it, but I think a lot of the character work was putting myself in the shoes of the characters and then going with my gut. I just did it twice. Shane did it too. We had a lot of conversations about it.

Check the review of the film

Ken: Shane is a very talented actor whom I worked with on my first movie. When I started writing this second film, I called him up and said “I want to develop this character with you, will you come do a few workshops with me in a theater studio? Sit down in front of the laptop or phone, get in the head of a willful, impetuous, annoying young YouTuber”. And he did. He sat there, we devised a few monologues, created some fictional posts.

At the time, I wanted to cast Shane. But between the first draft and the time the funding came in, five years had passed and frankly Shane had gotten too old to play an 18-year-old. Then I met yao in the Singapore theater scene around 2018. I'd written a play called “That's What Happens to Pretty Girls” about the MeToo movement in Singapore, yao was part of the ensemble. We got to know each other better, we sat down at an Indian prata shop and I pitched it to him. We got on and were keen to work with each other.

yao loved the idea that the brothers would be twins, but I needed him to further develop the characters, make them his own. Story-wise I knew it had be structured with Sean as the main character. But the depiction of Ricky is important in one very specific regard. In a country where homosexuality is a crime, I wanted Ricky to grow up in a home where he has no baggage. He's loved and accepted unquestionably, the kind of gay youth that doesn't have any shame or struggle about coming out. Very unremarkable, very banal, even. It's only when the brothers go out into the world, out of the safe bubble of their family that they experience the hatred of society. And that signals the dawn of Ricky's political consciousness. That's when he realizes that the ease with which he came out may not be the case for everyone else. To be branded a criminal, or be seen as inherently depraved, is a deeply problematic and traumatic thing in the kind of First World country the brothers live in.

Though we see this through the entire movie, the fact that so-called centrist views in fact support the oppressors is most visible in the scene between Nancy, who is a teacher, and the principal of the school she works at.

Pam: I think the film tries to draw some attention to the difference between institutional problems as compared to personal responses and how the two just might not meet. Like the characters of the cop and the school principal. When the mother asks the cop if he's offended, he immediately retreats behind a seeming position of neutrality. He feels that he's unable to take a personal stand for anything. The school principal too. They're quite practical about how to manage difficult political issues. The default is to just apologize and not rock the boat. They try to depersonalize the politics, but that's very hard to do it when it comes to your own friend or family.

Ken: The way Nancy defends her sons and especially the way she defends Ricky, that's the most important thing for me in the film. Though the movie takes you on a rollercoaster ride, its most radical aspect – the part I'm most proud of – is its depiction of queer normalcy. Nancy just loves her sons, their sexual orientation is a non-issue, it's no big deal. It's ordinary, unremarkable, mundane even. In the context of a country where you rarely see LGBTQ characters in mainstream film or television – and if you do they're always portrayed as somehow problematic, abnormal, weird or morally-compromised – it was important to me to show Ricky as an ordinary, unfettered, playful young boy, whose family loves him – because why wouldn't they?