Third part of a series of movies that focus on sexual awakening, girlhood / young womanhood and independence, by the wife and husband duo of Huang Ji and Ryuji Otsuka, following “Egg And Stone” and “Foolish Bird”, “Stonewalling” is a very personal film, which implements though, the personal experiences of the two filmmakers in order to show a very realistic image of the modern day metropolitan China.

Stonewalling is screening at Venice International Film Festival

20-year-old Lynn is instigated by her boyfriend, and his family to a point, to follow a very particular path in life that has her attending a flight-attendant school, learning English, and agreeing to every whim of his, while he is away on modeling and party hosting gigs. When she finds out that she is pregnant though, her life turns upside down, particularly because she eventually realizes she wants to keep the baby, despite her boyfriend's insistence to get an abortion. Lying to him about getting rid of the baby, she actually returns to her parents who run an obstetrician clinic, but have their own share problems. As time passes, her decision changes to giving the child away after carrying it to term, a goal she pursues with the help of an acquaintance of her mother. When Covid strikes, however, things become even more complicated.

Built from interviews with college women happy to invest in themselves, observations of a post-Tik Tok China, and their own lived experiences, “Stonewalling” presents life in modern day China in all its glory, through the year-long story of a rather normal girl who finds herself in an extreme, but not so unusual situation. What the filmmakers take care of from the introductory scene, is to highlight how disconnected Lynn feels from her overall environment, as shaped by her boyfriend's life, who seems to think he essentially owns her, as his attitude when she announces her pregnancy eloquently highlights. This disconnection is highlighted both from the script, but also due to the excellent cinematography by Otsuka, who always records her placed in a distance from everyone and everything, and to Yao Honggui's highly naturalistic acting. It is this distance that also allows the filmmakers to comment on a number of aspects of the current economy in the country, and the effect it has on the lives of people.

In that regard, the concept of multi-level marketing schemes is explored quite thoroughly from Lynn's mother's dealings with Vitality Cream, which actually take a significant part of the movie. The “show” of the whole thing also depicts how these schemes are marketed, with the ones in charge convincing “everyday people” about the abundance of opportunity that exists in this kind of business, despite the fact that the whole thing is evidently a sham. A second major arc focuses on the concept of ovum donation, which seems to have become quite popular among young women in China, while a third deals with gig-economy, as we watch Lynn taking one odd job after the other. In another significant remark which is presented through both Lynn and her mother, the directors highlight how the country still remains a patriarchal one, with men being the ones “in-charge”, even if in the case of both women, the push-back is quite significant.

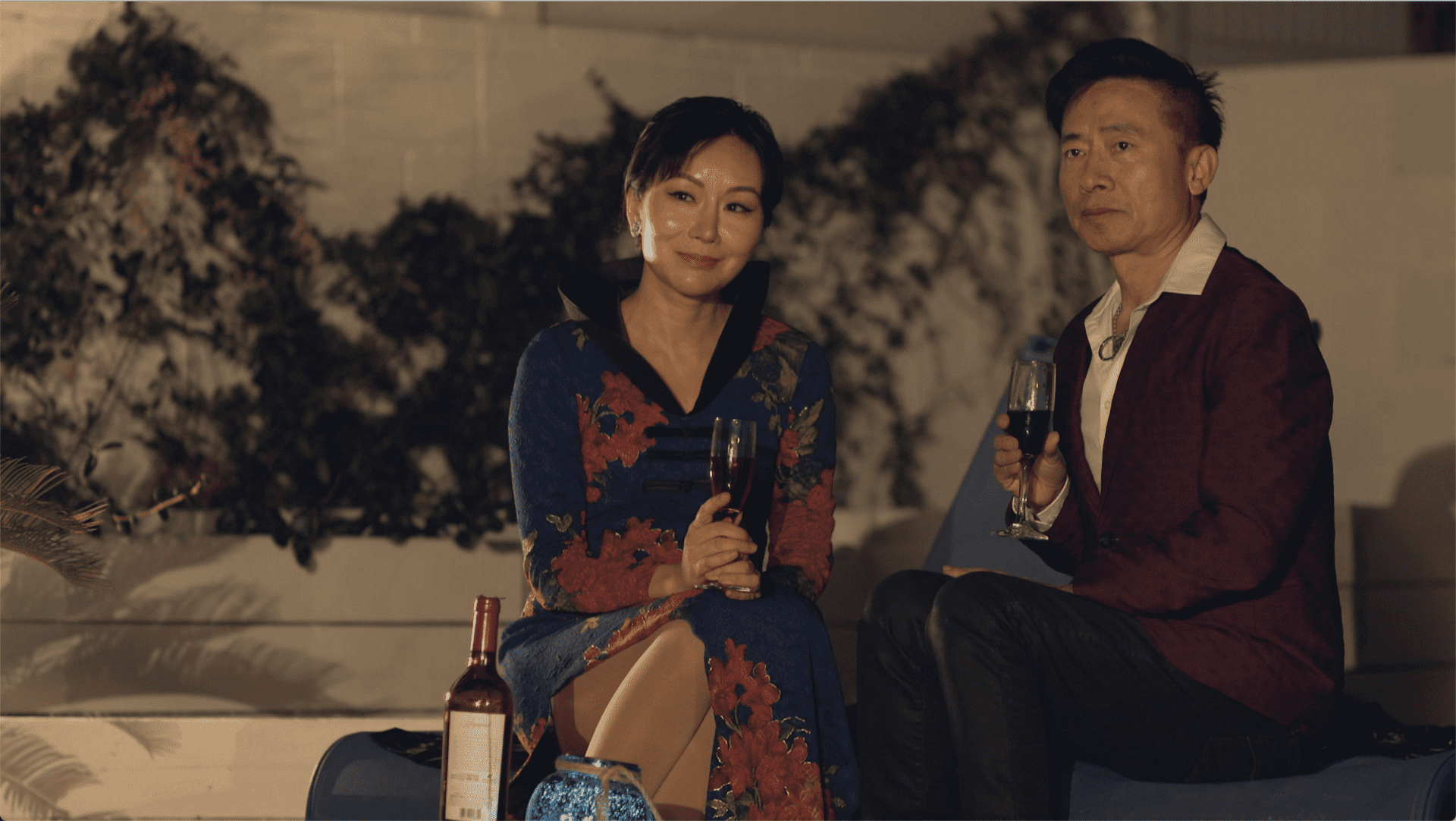

The depiction of Lynn's parents, who are actually played by Huang Ji's own parents, is quite rewarding here, with the way her mother tries to fix a problem she caused, being the source of a number of the aforementioned comments, as much as a sample of how marriage worked among couples of the previous generation.

In general, realism is the main element here, with the portrayal of every aspect of the movie permeated by it, in a way that makes the movie frequently look like a documentary, with Otsuka's cinematography and the overall acting being the main mediums of this approach, in a style quite close to European art-house cinema.

At the same time, though, and despite the fact that all elements of the movie are quite interesting individually, at 147 minutes, “Stonewalling” definitely overextends its welcome, both due to a number of scenes that could have been omitted and others that linger for much longer than they could. The generally slow pace of the movie as dictated by Huang Ji's own editing, although fitting to the general aesthetics here, does not help in that regard either, resulting in a film that becomes difficult to follow after a fashion.

As such, “Stonewalling” is a rather interesting and quite well-shot movie, which sheds light to a number of aspects of Chinese society rarely depicted on screen, but also a difficult one that demands much patience from its viewer and is essentially addressed only to art-house fans.