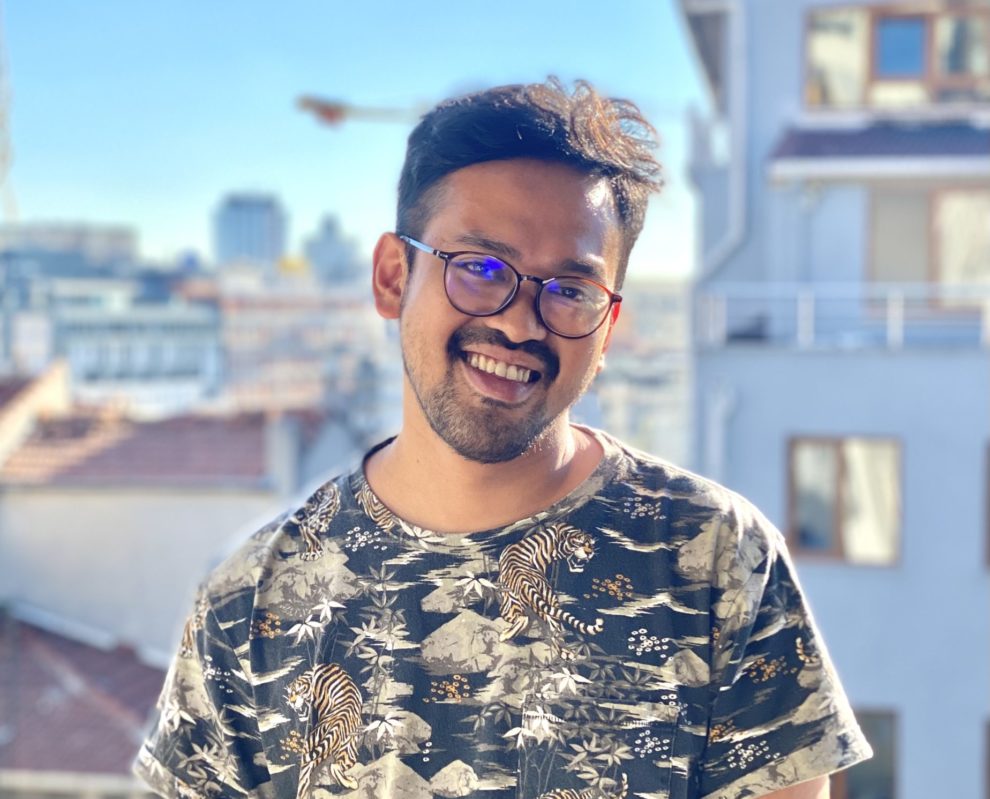

“It's a big time for us,” said Indonesian filmmaker Makbul Mubarak, whose debut feature has just premiered in the Orizzonti section of the 79th La Biennale di Venezia and is currently being showcased in Toronto. After Edwin, Kamila Andini, and Mouly Sourya, Mubarak is another Indonesian filmmaker whose presence at the international festival was well-noted and his “Autobiography” was granted a FIPRESCI award. Mubarak, formerly an established film critic and a director of two short films, prepared his “Autobiography” through a formula that many seem to follow these days. With the opening credits of the film, what lights up is a number of co-production projects and script labs – including the one in Torino – friendly reminding of the international nature of the project.

Indeed, the co-production opportunities seem to be on the rise for Indonesia – after the international successes of the aforementioned filmmakers, there is definitely a possibility window for many upcoming filmmakers who can apply for the funds outside of their country (some of them trying their best even in the territory of Netflix). On one hand, the Indonesian landscape has become somewhat of a bottomless pit of contexts that resonate with a universality that is far from the banal; on the other, the potential of lavish folklore asks for a cinematic representation. The interest to indulge in the co-productions, however, comes with a risk as many – the well-tailored formula might result in well-tailored films. This is not to say that emerging talent shouldn't take their chance; quite the opposite, the rise of the opportunity pool makes it even more exciting for Indonesian films to come in the nearest future.

Autobiogarphy screened at Venice International Film Festival

“Autobiography,” tells the coming-of-self story of Rakib (Kevin Ardilova), a teenager, whose quotidian routine as a housekeeper of the rural mansion becomes riled with the unexpected comeback of the lord of the house, Purna (Arswendy Bening Swara), a retired general who turns into a politician running for a seat as a local mayor. Having his gaze fixed on nothing but the rapid development of the town, Purna is a living tour-de-force of fear; he's manipulative and demands obedience equal to that of the military standards. Early into the story, Rakib even puts on a uniform and just like Diao Yinan's protagonist from “Uniform” (2003), he goes onto the streets to test the limits of his power. The real question for the young man, in his attempt of minting one's autobiography, becomes the question of his agency. And so does the film unfold – as a generational tale of those whose adolescence is paired with the shadow of Indonesian culture of violence and fear.

We spoke with Mubarak on the occasion of the 79th La Biennale di Venezia. During a sunny afternoon at Lido, we discussed the ideas behind the film's visual language and thematic notions, the experience of dictatorship in Indonesia that shaped the film's premise, the supposedly neo-colonial aspect of co-production platforms like Torino Script Lab, and the Indonesian film landscape.

Your background is film criticism and you paved your way through a co-production model and script labs. How did that work for you and what was the starting point?

I think it all started with our government actually. For some time now, the Indonesian culture sector has been engaging in small initiatives. A part of it was the contract with Torino Script Lab that guaranteed two Indonesian projects in one year to be presented at their market. The first year was “Autobiography” and it was one of the two projects that were invited to the lab. For many included in the film, the question was – how does actually a lab like this operate? I myself have never been to a project development lab before. But we went there and this is where things started to happen. Since there are so many people engaged in the whole process of working on the script [at the lab], everybody wants to somehow have their share; people simply start putting their story into the film's story. The first draft of my debut was very badly done. And when it's bad, the others will recognize that by implementing comments on the script, so that we can all make it a better one. The idea is to help the new guys, like me, to become better as well. I imagine that Edwin, Mouly [Surya] or Kamila [Andini] don't receive such treatment anymore when they participate in script labs. Especially Mouly, I think, as she has just wrapped up a Netflix project in New Mexico, which, I guess, will become a leading example for many other Indonesian filmmakers and I wouldn't mind jumping on a project like that as well. It's because I can't rely on the labs forever. There's a limitation – it can be only done as your first or second film. After that, you're on your own.

You've mentioned other filmmakers from Indonesia and how they're doing outside of the country. There's definitely a buzz around them and the awards at international festivals, good reception and the general quality of the films indeed point to a certain peak. It seems as if it's a good time for Indonesian Cinema, a formative turn.

I also think that it's very interesting. The good job we're doing is keeping the momentum. Everybody strives for a Golden Leopard now. So this gives us some room to work with. Kamila also won in Berlin. I'm not hoping for a win here, but I think being in Orizzonti is enough. [laughs] Venice, Toronto, Locarno – the presence of Indonesian filmmakers there is a great indication that we're consistent: we keep on making films. There are a lot of exciting titles coming up from a new talent pool very shortly. And not everyone's doing it through labs and co-productions. In a way, I wished it would be different, as there are so many talented people with whom you can collaborate – I think such joint projects can push the film further.

What's the direction for Indonesian Cinema then?

I guess we're opting for this way because the interest has to be answered. And you have to keep that flow going. Otherwise, there would something else, another trend to lean on. So we kind of have to keep doing this – participating in these projects while we can. When we [Indonesian filmmakers] apply for the lab, and if we know that someone else is also applying, sometimes we let that person apply first. The idea is to learn from letting things go. We don't compete. At least most of the time. Unless we have to. If we do, then we strive to make it for the better good, so that we can eventually collaborate. One person goes to the lab first, and then the other, and then the next one. It makes things circulate and Indonesia stays on the film map.

You said that the first draft of “Autobiography” was badly written. How so?

It was a poor script because I intended it first as a black comedy and it wasn't supposed to be a feature film. But soon enough it became clear it won't be a short film, because at some point, during the process of writing the script, the page count hit 70. I thought it was way too long, but one of my friends gave it a read and he encouraged me to continue writing until the ending would come to me. And it did, eventually, with 140 pages or something. It was darkly funny, but also somewhat very Indonesian. It had this peculiar sense of humor that we, Indonesian, love; but it was also the case that people from abroad didn't respond to any of it, didn't really get it. Humor is something very specific. It's cultural. Aside from that, the characters didn't have depth. Now when I look back, I kind of see the old protagonist as merely a pamphlet, a carrier of messages rather than a real person. So this was something we focused on during the lab. But it wasn't until two years ago that I finally was able to say to myself, “this is the script that I could see on the big screen.”

With so many Southeast Asian projects being developed over the years at script or film labs connected to the whole festival landscape, I'm wondering, don't you have a feeling that the model proposed here is a bit superimposing on what you'd supposed to do with the film? You mentioned that the original script was poorly written, but then again that its humor was a bit hermetic. What I'm also hearing is that there was a certain rawness that wasn't appealing to, perhaps, Western audiences. I don't want to sound harsh, but feels a bit colonial, don't you think?

I've been thinking about this a lot. At first, I was like, “are they changing the film to something it is not?” But in the end, it wasn't the case, because I myself felt that the characters weren't believable, that they weren't alive. And for me, it is universal. Whether you make a film for one village or the whole continent, your audience needs to believe in the premise of your story and your characters. Lots of people have been asking me about my presence on those international platforms, suggesting the colonial background of these projects. But you know, what I found during my time there, is actually a lot of curiosity. Everybody wants to know about my story, my country, and my context. The question becomes ‘why' – why do such kinds of people [like the general in “Autobiography”] exist? And we try to answer that; it becomes the reverse of colonialism. Simply because the others just want to get to know about you. I'd say that the issue of calling these platforms colonial, a harsh word indeed, comes from unfamiliarity. People insisting on the colonial nature of these projects might not know about us – those, who benefit from that opportunity. For us, filmmakers from Southeast Asia, it's our first job to explain the ground where these ideas grow. And we're doing this thanks to these platforms. Once we get someone's attention to grasp the essence of our stories, we can move on and start working on the more technical aspect of the story, like the script itself.

Since “Autobiography” derives from your story and your background, I was thinking about how essential it is, for upcoming filmmakers, to rely on personal storytelling. It seems there's this extra attention for personal tissue.

I think it's not essential. Actually, lots of my friends from Indonesia are telling stories that are not personal. They go for what the market wants. And we have a huge market – we need to pay attention to that, too. Simply because we can't lose the trust of our audience. But with personal stories, it's definitely a thing when it comes to Torino. It's the first question: “Is it a personal story?” If yes, then you can move forward; if not, “try somewhere else.” But it doesn't mean such dynamics superimpose anything; we go there if we really think it suits our approach. Because when it doesn't, it can destroy you. I know a lot of people who went to the lab and came back with nothing but hate. It's not for everybody – some people don't like other people engaging in their stories. I think it's important to know where your story comes from. There is, however, something interesting happening during the script labs – depending on whom you're working with, you can experience lots of contributions from a third party. Like, people want to contribute to your storytelling by implementing their take on the subject, or their stories. But I don't blame them; it's a joint process.

Watching “Autobiography” made me think of other films that depicted an Indonesian reality filled with atrocities and a persona who commits them: Joshua Oppenheimer's “The Act of Killing” and “The Look of Silence”. Do you think the legacy of these films influenced the way you wanted to depict the characters in your film?

I would say not so much because the event itself and the burden of history are much bigger than the film. And there are hundreds of Indonesian films depicting that event to start with. Naturally, everybody's attention is pointed toward Joshua because his film is the biggest one and probably the best. However, in terms of approaching the issue from a cinematic perspective, our films are different. Joshua relies on the process of reenactment. He lets the body go through the trauma again, to experience it for the second time. Through that, he tells us what these people felt and let us, the audience, also feel the same. “The Act of Killing” is about the power of remembering. And I'm saying this also from a perspective of a film critic, but truth to be told, memory can be painful. But as time unfolds, the wound from forgetting is even more painful. This is where Oppenheimer stems from. “Autobiography” is different, because it comes from a point of view of my generation, people who didn't live during that era. When the dictatorship ended, I was eight years old. My concern comes from the fact, and I try to depict it in the film, that it did end and what we can do with this. We have Twitter, we have Wi-Fi, and everybody can talk shit about everybody. Yet, we're still feeling the afterimages of the dictator's presence. If you go harsh on some powerful figure, they can do something to you. Those people who were in power back then, they're still in control. And it's not like it's diminishing. They still do own the majority of the resources of the country. So the question is – what has, in fact, changed? Like really changed? The democracy that we have now – is it real? Or maybe it's just a facade of the old times, a dictatorship or oligarchy? So my film is the point of view of the post-dictatorship generations and that's the reason why the general is not the main character. While in Joshua's film, the main character is the perpetrator.

He's not a perpetrator, but he's evolving. One of the main motifs of the film concerning him is his body and the performativity of the uniform. Once he starts to wear the military wearing, his personality, and even his movement change. The uniform becomes a symbol of something he can't have: a performative force of power he somewhat naturally starts to embrace.

The symbolic meaning of the uniform is the first layer of the film. But underneath this, there is something that stands as unnatural, the concept of a borrowed power – something that you can't have on your own, yet you can borrow it from someone else, and then, perform as you own it. This is something that I observed as very common in Indonesia. It's because we lived under the control of some bigger power for such a long time; we can't rebel against that. So if you want to survive, and you don't have that power, you just step into someone's shoes. I've seen fighting scenes on the streets where people would just say at some point, that their cousin is in the army. It can scare people off. It's not the power one owns; it's not my power, it's not me, but it's powerful. And it's a thing, it happens a lot on many grounds, and it negatively affects people. That's how people survive in Indonesia – by performing a borrowed power they don't have. I guess it's a perfect encapsulation of how a totalitarian system works. In Indonesia, it's very common to use someone's power to achieve things. Someone's cousin who gives you a free driving license? No problem. It's a crooked system. I tried to look into that system and what I intended to do, is to look through the most quotidian and mundane things. I felt that the uniform will work best because you can see it everywhere on the streets. It's integrated into the real tissue. Some people wear it but they shouldn't; it's not like everybody's a police officer – you actually can't really tell who's who. But in people's minds, it's always better to be safe than sorry, so everybody complies.

It seems that there is this constant loop of apologizing in the story. In one scene the protagonist apologizes to the general, but once he wears the uniform, other people start apologizing to him. Where does that idea come from?

I think the biggest issue that should be addressed at the end of every conflict is that someone needs to eventually apologize. There's a need for resolution and sometimes the only way for achieving it is to apologize. When Eichmann was trialed in Jerusalem or during the Nuremberg trials – everybody demanded an apology from the regime. In the case of Indonesia, there was no margin for any sort of apology. The state officially apologized to the victims, but has it really changed their lives? Was there any forgiveness? Not really, because both the perpetrators and the victims have already died by then, so it's more like forgetting rather than forgiving. I think that in Indonesia, people are sometimes just so afraid of doing things. Instead of acting upon it, they'd rather just let it go and forget. But it doesn't mean to forgive, as it's difficult to forgive the death of more than two million people. In the film, the concern of apology might seem to be a bit ironic when it comes from the general himself. It's the core value that he teaches to a young man; an apology is like a present, a gift, he says. But in fact, it becomes a toxic value when it reappears in the film.

How does it translate for the inter-generational dialogue? It's also a huge part of the film: the conflict between the generation of youth – your generation – and the one of the dictatorship, embodied by the character of the general.

Indeed, beneath the cyclical structure of reciprocal apologizing, there's this longing for resolution for our country. Especially between these two generations. The state apologizes, they give some reconciliation money, a superficial makeover prize. But do they give that to those two million people who have died? I don't think so. It's only acting. And I talked with some of the families before I made the film. And what they told me is that it's way easier to forget, because they know they will be never able to forgive.

The collective ground of the film is also incredibly well designed in the way you play around the space. You rely on the city as a narrative and textual device – there are a lot of campaign posters, so the city itself works as a political text; but also in the way you move around the space with a car. The point of view of a car driver is extremely important here, as you enable your character to move freely and the audience can observe, notice, and pay attention. How did you work on that?

The space was very important for me and Wojtek [Staroń; the cinematographer] because we wanted to show it from Rakib's perspective. When he's with Purna, the general, he's not himself. Even before the uniform, he has to behave, he has to perform. He's always in the motion of being someone else. That's why when the general arrives on the first day, Rakib puts his t-shirt on, even though he didn't wear it before when he could be on his own. With the arrival of the general, he has to embrace a new identity. For that reason, the space is very limited for Rakib. He's like prey. The camera sticks with him. But there's an image outside of the frame, too. This is the space that Purna has control over. The audience doesn't get to see it, because I wanted to put the viewers in the powerless position; in a way, there's something beyond your grasp and it maintains control over what you see.

Could you tell me more about how you intended to design this off-screen presence?

I wanted to highlight the interactions between the on-screen and off-screen scenes. We opted to use this very particular lens that distorts the edges of the image. It's a very old Japanese lens, made in the 60s, called Kowa Anamorphic, which we brought from LA as we couldn't find it anywhere in Southeast Asia. But the way it distorts Rakib's point of view and his perspective on space is very peculiar – it is supposed to put the viewer's attention into constant questioning of one's perspective and position. It's all about constant change. The presence of one character influences the way the other behaves in space. With Purna, Rakib is different, and so he occupies the space differently; when he meets those below him in the hierarchy, the space changes as well, because he's not the prey anymore but a predator. This interchange of space became a very dominant vessel for us because it enabled us to work on role-playing as well. And after all, the film is about performing and embracing different types of roles in one's life.