Danny Yung is an experimental art pioneer and one of Hong Kong's most influential artists. He is a founding member and co-artistic director of Zuni Icosahedron. In the past 40 years, Yung has been working extensively in diverse fields of arts, including theatre, cartoon, film, video as well as visual and installation art. In the span of his 50-year artistic profession, Yung has been involved in over 100 theatre productions as director, scriptwriter, producer and/or stage designer. His theatre works were staged in multiple cities across the world, including Tokyo, Yokohama, Toga, Singapore, Jakarta, Taipei, Shanghai, Nanjing, Shenzhen, Brussels, Berlin, Munich, Hannover, London, Lisbon, Rotterdam, Dubai and New York. The artist keeps a close eye on the arts and cultural policy and on education development in Hong Kong and the Asia-Pacific region. He currently serves as chairman of the Hong Kong–Taipei–Shenzhen–Shanghai City-to-City Cultural Exchange Conference and is a member of the Design Council of Hong Kong. He was also appointed the inaugural Dean's Master Artist in Drama of the Hong Kong Academy for Performing Arts in 2013, and he serves on the Management Board of the HKICC Lee ShauKee School of Creativity and the advisory boards of the Department of Cultural Studies of Hong Kong's Lingnan University and the School of Drama of the Hong Kong Academy for Performing Arts. In 2009, Yung was awarded the Cross of Merit of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany in recognition of his achievements and contributions to cultural exchanges between Germany and Hong Kong. In 2014, Yung was awarded the Fukuoka Prize (Arts and Culture). In 2022, Yung accepted the Award for Outstanding Contribution in Arts presented by the Hong Kong Arts Development Council.

On the occasion of “Interrupted Dream” screening at InlanDimensions, we speak with him (on a boat no less) about theater and cinema, boundaries, Chinese opera, experimentation, cross culture, Louis XIV and many other topics

Your career in theater is quite well known. What about your dealings with cinema though?

At one time, I was very much involved with film, I would go and see 5 movies a day. During the 80s, I was an advisor to the Berlin Film Festival and London Film Festival and New York and San Francisco Film Festival. In the 70s, I traveled all over China, I visited various film factories and met many important film people who were most inspiring. That was probably one of the reasons I was invited to be an advisor to all these festivals, they would always ask me to recommend films. I was recommending filmmakers like Hou Hsiao-hsien and Edward Yang who were just starting their careers, who would also come to me asking advice on how their films can be more exposed. In my travels, I would come across films that you cannot just pass, and always tried to promote them. In China, it would be Zhang Yimou and Chen Kaige at the time, who were very fresh. In Taiwan there was Hou Hsiao-hsien and later on, Tsai Ming-liang. That was a generation of filmmakers who wanted to know what was happening outside their country and there was not much access.

When Tony Rayns was in some of the festivals with me, and we exchanged notes, he always asked me, “How about this one?” after coming out of the screening room, where usually very few people would watch these Asian films. I also exchanged notes with Marco Mueller, from Venice Film Festival.

I was living in Beijing for three years and I would stay in a place called Friendship Hotel. And I shipped all my collection of video versions of films to Beijing so I would get to enjoy watching movies. And many local filmmakers came, wishing to check my library. Later on, I donated everything to the Beijing Film Academy. There was a time I told them that there are films beyond Hollywood and many film movements in Europe worthy for us to study and discuss.

But you don't watch movies any more? Is it because you don't like today's movies?

It is not that I don't like them, just that I have accepted that after the particular decade I mentioned before, movies are pretty much chosen by the film festivals, by their curators. There are certain guidelines they see the film world through, and how they choose the titles screening: films about children, about education, taking place in rural areas, they all love it. So they always pick very similar films. Eventually, I started watching only documentaries, I found them to be of interest for a while.

Why the need to experiment in your works, why not follow the “regular path”?

As I mentioned, after watching so many films, I could see the formula of the narrative structure of the film, even from the first 10 minutes of the movie. So I was more interested in watching movies that were six hours long let's say, for example Fassbinder's “Berlin Alexanderplatz” which is a 14-part mini series and also very short films, animations. For a little while, I got very interested in commercials, because they try to sell something in such a short time, and you really need to know how to sell it to do so. I was working for TV for a year in the 80s and I know how the industry operates, how they program their content, and I was really interested in commercials. I was programming director so every time a commercial appeared, the volume was 20% higher, that made me very much disturbed as a way to make certain commercials get their attention. Of course, this has to do much with the financing of the TV operation.

To get to the play screening in InlanDimensions, “Interrupted Dream”. Why did you chose the “Peony Pavilion” as its base?

I thought theater making is like rediscovering the greats and of course this classic work from Chinese cultural history is about dreams. You start wondering why there is so much to dreams, is it an extension of reality or are dreams a way to talk about the subconscious or hidden emotions. Of course, for many really good playwrights and poets, dreams are a medium to talk about reality.

Last night, during the Q&A after the play, you talked about boundaries. Can you elaborate a bit more, also in connection with InlanDimensions?

I am very conscious of boundaries. For example, we are on a boat right now so we are bounded by water (laughter) and we are bounded by lights and people and I am fully aware of these elements, how they will affect our conversation. This is something that I am always very concerned about.

I think theater also has a very long history, film history is shorter. As I was saying earlier, in the film industry, feature films have their boundaries of how long they should be in order to sell. The scene, the structure, all cinematic elements have their boundaries, at least unless you become a very prominent filmmaker, you are significantly bounded. And this boundary is set by political reasons, by economic reasons, or physical or cultural reasons. We all know that the rules and regulations change all the time; we certainly hope that artists can loosen up the rules and regulations or at least challenge them and make much more interesting use of them. But from what I have seen, the film industry is very much affected by commercialism. Theater has also been bombarded by it and it comes down to, perhaps, the festival circuit that is very different from the regular film and theater setting. Usually, the film circuit appears to be less affected by commercialism, and financial, political, and cultural boundaries.

After a while you notice though, if you talk, for example, to Nikodem Karolak, he can tell you that the reason he is so focused in Japan is because he understands Japanese funding, so that is one of the boundaries. Without Japanese funding, probably this exported work would not have happened. The same applies to Hong Kong, so he is also struggling with trying to find independence for his festival. But then of course, InlanDimensions takes place in Poland, and since he is Polish, he has access to all the network, so he is familiar with the public, the press, the media, for example asking you to join the festival. So he is becoming a bridge, moving beyond boundaries and it is interesting to see how he builds this bridge.

I was telling him, “Let's define what festival is all about, and we can have debates and discussions, aside from what is happening on stage”. What is happening on stage is probably there to trigger the discussion and the debates and that would be good. When I was in the Grotowski Institute, they asked me to be a key speaker and talk about creativity and institution. Does institution really help creativity? It depends on what kind of institute it is and who is managing the institution. Even a theater group or festival groups are institutional structures and have to be managed and they create a type of boundaries. But talking about it is so easy, knowing it and finding the way to handle it is the part that is challenging.

And what about this red line, appearing all over the play?

I started using the red line a long time ago and it was most appreciated by Edward Yang. He came to see my work and he said, “Ah! The lines!” (laughter). It was during one of my journeys performing in Taiwan.

Has censorship also reached theater in Hong Kong?

Censorship has existed for many years, it has to do with the overall structure of the organization. To them, anything to do with mass media has to do with propaganda, with ideas. But it has loosen up compared to the past. One reason is because of economic development, and the pluralism that follows economic development.

Are there any people you consider quite significant collaborators in your work in “Interrupted Dream?”

I have many collaborators. I guess the first and most important collaborator, since I think music plays the most important part, was the composer and I also have a really good video maker, John Wong. He is now in the UK, and I told him how we divide silence and sound and I asked him about the whole demonstration segment and we discussed many many times about distancing ourselves from people's movement, and understanding people's movement. The second was structurally deconstructed in some way so you look at the view in silence and then you feel the sound and then you hear the sound and watch the clips. I worked with him many times, he is one of my very early collaborators.

The first time I saw his work, he was a student, so I wrote him a long letter, telling him what I saw. He showed the letter to his girlfriend (laughter) and his girlfriend said to him that he should answer it. And he did, he wrote me back. Later on he became a teacher and now he has emigrated to London. In general, he did very well with his career because his innovative work in multimedia is always sought after by the commercial sector.

Can you give us some details about the the cast of “Interrupted Dream”?

I am always looking out for who is doing what, in both visuals and music of my plays. Less so with performers though. In the 80s, when I first started, we were talking about collective creativity. You still need coordination with collective creativity but the openness in the exchange of ideas and experimentation is intense. This was in the 80s and this is how we gathered a group of very interesting and motivated individuals.

Check the review of the play

Can you give us some more details about Kun opera? Do you think that if someone understood Chinese or has read the “Peony Pavilion” they would understand “Interrupted Dream” better?

No one would understand anything better, but the thing is that not unless you go through the whole process of how works are being developed you can understand a work fully. The text of Peony Pavilion of course is always there: like if you don't go out, you never know what spring is all about. This is the regular text which appeared on the stage which was from the novel, not from the original play. Furthermore, when Xiao Xiangping is singing the play, no one can read the text because the letters are so small and also he is not following the text. I did it in a way that if you read it, it does not apply to what you have heard.

When I read the original version of Peony Pavilion, I thought that it could be very boring, but then it depends. Very boring in the sense that it is very very slow, but then it makes you think that people in the Ming Dynasty were very slow, that is why they could appreciate very slow music. Of course, we are talking about scholarly arts, we are not talking about farmers, who had their dance and songs fitting their laboring movement. But when you are a scholar in a library, doing Kun opera, you have all the time to listen to the music and to experiment singing. But it would be a very good experience to learn about our ancestors, about their concept of time and space. Because Kun was originally from the library, a scholar's book chamber, so the singing would not be so loud as what you heard in the play, and the audience consisted of about a dozen people, although it evolved to more and more.

When the emperor banned the work and then he turned around and said he wanted to see the work, he saw it in the palace with others, his consort. Then it became more and more like a performance in a formal space. I think Kun at one time was focusing on singing more than the script. So the songs or the songlets were very much how people nowadays go to a rock concert, but you can imagine that, at the time, there were no loudspeakers, so you had to choose the right spot to do this event. I remember an outdoor event with a 20000 audience, which meant that the performers must be so well trained to extend the sound to all the audience. If the audience is so big, the performers had to be trained to deal with the audience. And the same thing with movements, it is no longer a very delicate movement in a library or in a scholar's chamber, instead they exaggerate the movement. This has to do with the external environment.

Do you think about who is watching your plays, about your audience?

Not as much as theater makers because I know why I was experimenting. I know what I was doing and most importantly, I hope my collaborators know too.

Can you tell me a bit about the inclusion of Louis XIV in the play? His presence seems even more outside the box…

In the beginning of my wish to adapt Peony Pavilion, I was reading about Louis XIV, and his admiration of the Chinese arts and Chinese theater, and this was the beginning of the Chinois movement and how the West looked at the East for the first time. And it was really interesting to me to see how much he understood the differences between us and the West. He thought that he was the center of the world and probably thought that everyone coming outside of France came to greet him. He was sitting in the center of the court and there came an Indonesian artist, a Thai, a Japanese, a Chinese and they were all there. In the beginning, they were asked to dress in their local attire and later they were asked to dress like the French, in a balloon dress. His love for Chinese artifacts and Chinese songs, however superficial, triggered the entire palace; all the court ladies were eager to learn about Chinese theater and dance.

And then you have the balloon dress. I was thinking if the balloon dress had Indonesian influences, what would their movement be like? If they are dressed by, let's say, a Japanese person, how would they present themselves.? I am very neutral about colonization, unless it is really invaded into other people's territory. But the idea of cross-over is like cross-dressing, you start to think when you are from. When you cross the border, it triggers more space to think. That is why I was saying yesterday when this person was asking me about my experience of learning since I was four years old when I left Shanghai and 17 when I left Hong Kong. Each culture shock could be very damaging but it could also benefit, and the idea of crossover is to generate different ways of looking at one's self and looking at the world.

I think I became very much appreciative of Chinese classics, not when I was in highschool in Hong Kong but when I was in college, in Berkley, where they have a fantastic library. In Columbia university, the library is even more fantastic, you could see all these collections that do not exist in Hong Kong or Taiwan or even in China, because there is no political censorship in the US. I learned more about Chinese when I was outside of China.

The inspiration coming from the classics instigated me to test the structure of narrative of what they are doing. The lines suddenly become a new dimension, it is like if you don't go to the back garden, then you will never see spring, even if you don't go to the theater, you will never experience something exotic. The idea of going out, crossing the boundary is the part I knew we were all very fascinated about, we always want to go out from our own boundaries and that is where we can see better and think better. Like, my original work in 2019 was based on a June 4 photograph. In Tiananmen square, there is a huge heroic statue with soldiers, farmers, sailors, maybe twice the life size of people and the photo I had was of students climbing on top of it, so this is about 20 ft from the ground and the statue was full with students. When they are higher up, they see better, they see further and are all eager. This whole drive of people who want to see better and see further away. Of course, the challenge is, “then what?”, if you see better. Will you be a better organizer, a better leader, or is it all just out of curiosity? The whole discussion about wishing to be higher up for the purpose of seeing better, does it make you think better?

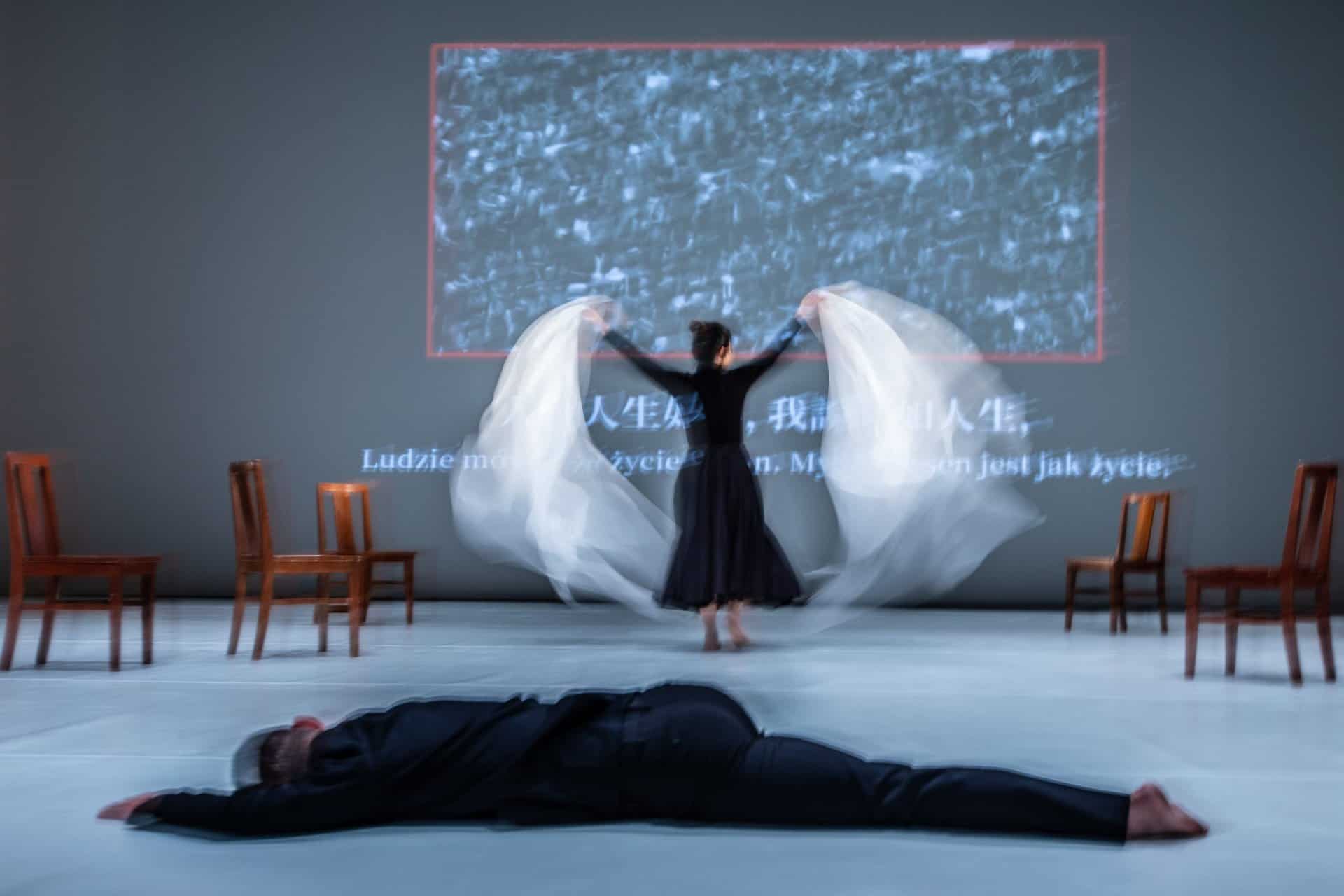

Let's go back though. In the 2019 piece, I was talking about people who were on top of the statue and the people who were climbing up and one of the students fell down and died. Therefore, we were discussing the meaning of death, of wishing to go higher up. Later on, I abandoned the whole idea of that version. However, there is always a person lying on stage. So there are parallel streams of talking about Louis XIV in the palace, about chinois, about imitating, of if cross culture can be achieved through military power, about who is creating the future culture, I think these were all the debates three or four years ago.

When I was working with a group of artists from Indonesia, from Thailand, from Cambodia, from China, from Japan and one from Malaysia, we had this discussion of how the West looks at us. Will we really know better if we perform for the Emperor, what is the deeper meaning of this type of performance? How do we feel when we are performing for our own leaders? And this is exactly what is going on because we are all performing for our own leaders. I think Louis XIV was a very interesting case study. Of course it triggers many cross cultures and many operas evolved from that time period. The musical influences are also there because the Emperor was advocating exoticism from the East.

What do you want to do going forward, are you working on anything new?

I am working on another work, it is called “Birth of Tragedy” by Nietzsche. It is a record of the time he was going through his brain about the two extremes in Greek art, Dionysus and Apollo. I find Nietzsche interesting as a character. He is a philosopher and I am also fascinated by his relationship with Wagner, whom Nietzsche hated. Wagner is so manipulative and very powerful and it is so easy to be emotionally reactive to music and all this manipulation of sound. That would be another focus I have been thinking about.