By Paweł Mizgalewicz

Every fallen rockstar was once a child that just plainly had a ton of fun playing music. As obvious as this sounds, it's a fact that is not too often mentioned in Western cinema. Whether we are watching another comprehensive biopic or a film about a rockstar that has already hit rock bottom and fully jaded (be it “Last Days” or recent “Taurus”), the fame, success and drugs tend to be a more popular subject than the simple pleasure of making sounds and creating your own thing. Now, if you ever wanted to inject a story with a childlike sense of pure fun, a playful tone and anything-goes attitude, you would hardly think of other directors than Masaaki Yuasa. His story of a rockstar is something else – it is, as he said to the audience after the Rotterdam screening, driven by this “dream of purity”. The uncommon combination turns out to be a winning formula in “Inu-Oh”, a story both very Western and very Japanese, a film of both darkness and joy, stillness and music. The result is definitely childish – but in a very profound way.

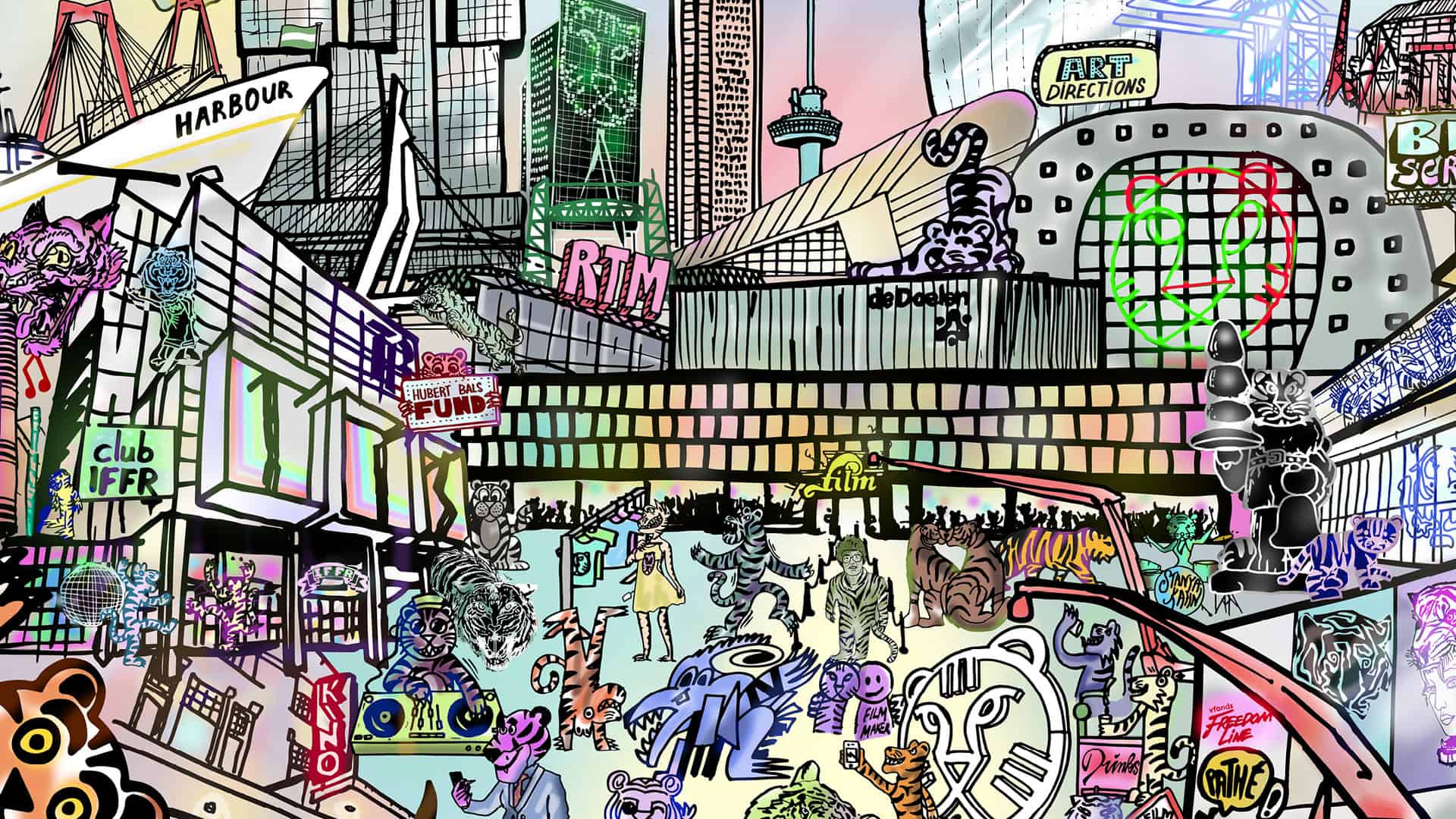

Inu-Oh is screening at International Film Festival Rotterdam

It might be considered a little spoiler that this is a rockstar story, as you'd never expect that looking at the first scene. Yes, it is set in the feudal Japan of 14th century, and opens with an act of a fantasy that seems more classical to the era – wars between emperors, a complex net of political conflicts, katana-wielding samurai, a wooden chest at the bottom of the lake, and in the chest, a cursed sword. But Yuasa was correct to assure the audience that the knowledge of Japanese history is not important to the enjoyment of his film that is “first of all a musical act” (even if I recommend paying attention to the dialogue, as all the events – and even the names – do matter to the story).

After a first act as gleefully chaotic as we've grown to love in his films, the narrative does finally focus on the main thread – a blind boy Tomona playing music with his biwa, a traditional instrument not very unlike the modern guitar. Tomona becomes a monk, performing music basically as a ritual. The monarch values unity in his land, and so the music troupe is uniform – every monk with the same bald head, in the same gray clothes, playing the same tune to the same rhythm. As Tomona meets the titular cursed creature, he starts developing his own personal style, though, completely flipping the script. His story becomes one of a David Bowie or a Freddie Mercury, or rather – what could happen if you put those kind of characters in a feudal Japan setting. There will be fire breathing on stage, there will be a “stomp-stomp-clap” beat, and there will be an epic song of three acts taking us on a whole musical journey from classical vocal harmonies to a dancing groove, similarly to “Bohemian Rhapsody” but with its own soul. As it turns out, Inu-oh is a lot of rock and roll, dance and audiovisual spectacle, proving that Yuasa's vivacious beat always made him destined to create musicals. As a pure show, “Inu-oh”'s peak scenes exhilarate just like the best musical gigs.

Is this real life, or is this just a fantasy? A rockstar performance centered on medieval Shogun battles and magical persimmon trees might at first seem like a wild mismatch invented for pure absurdity, but as Masaaki explained in Rotterdam, this striking combination feels very real to him. “I think that before we used to write everything down, people had a lot more fun with the music”, he said. “All the stuff that Jimi Hendricks was doing with a guitar – if somebody was playing a similarly shaped instrument like a biwa, surely they also came up with the idea of spicing it up in such a way”. In this context, we may actually watch this whole positively crazy film as a surprisingly deep commentary on the history of Japan. “Unity requires order”, demands the emperor from his officers, and to execute his will, they proceed to clamp on all the originality that doesn't align with the official vision of music. The story of Noh theater becoming standardized by Zeami and practically government-regulated is its real history, indeed. It's become a very strong tradition, as we can see so many centuries later. In his film, Masaaki asks, though: what about the stuff that didn't make history? What passed unwritten, unrecorded? Most likely, he presumes, all the things that were just too singular, too wild, maybe too ugly to be accepted, or maybe too unique to be cultivated by society. It's not only a story of a rockstar then, nor only a fantasy childlike story – it's also a deep tale about how the history is written by the winners.

In the end, after all the spectacle, Yuasa makes sure that we never forget about where the story began, of children performing their music without any knowledge of either authorities or popularity, just playing together for pleasure. In a story where every character has extremely dark events happen in their past, or future, or both, coming back to those pure moments of childlike happiness is a very moving reminder that maybe our inner child is just another victim of history – another thing that we ourselves leave behind, forgotten long ago, not fit for this world ruled by order.