As we have said before, and as the reality of a number of countries no one knew much about outside of their borders for decades, comes to the fore, the stories witnessed in documentaries are revealed to be ones that go beyond any kind of imagination (script if you prefer). Asian cinema in particular seems to thrive on both, as a region where life was never as “normal” as in the West, with the category, as a whole, including some of the best films we have seen during the last few years, 11 of which we include here.

Without further ado, here are the best Asian documentaries of 2022, in random order, and, as always, with a focus on diversity in style, directors, and country of origin. Some films may have premiered in 2021, but since they mostly circulated in 2022, we decided to include them.

1. Imad's Childhood (Zahavi Sanjavi, Kurdistan)

Zahava Sanjavi followed the family closely for many years, in a rather difficult effort that had him and his cameraman, Heshmatolla Narenji, running around a 4-year old that never stopped, witnessing repeating acts of shocking, violent tendencies, which occasionally even turned towards them, although in vocal fashion. The result, however, is impressive, as the story highlights both the blights of war and the despicability of ISIS's actions, whose members seem to hold nothing sacred, including childhood. (Panos Kotzathanasis)

2. Sirens (Rita Baghadi, Lebanon)

In that regard, the relationship of the two girls with their parents, but also with each other, in an aspect that reveals another element of their character, and the tension that dominates it, eventually take center stage, even though music is always on the foreground. Their antithesis is quite intense actually, with Shery being quite open about her thoughts, feelings and sexuality, while Lilas prefers not to reveal almost anything. When a fight during a group meeting escalates, the dynamics are revealed even more, in one of the most impactful moments of the documentary. (Panos Kotzathanasis)

3. Table for Two (Kim Bo-ram, S. Korea)

At the same time, though, and despite her stoic acceptance of her daughter's quite pointed remarks, the pain she feels hearing her talk like that is quite evident, in an approach that, quite realistically, does not necessarily offer a catharsis or bridges gaps that were formed over years. Furthermore, and in an effort to analyze her protagonists even more, Kim also focuses on the story of Chae-young's grandmother, whose behavior towards her own daughter seems to be the root of Sang-ok towards hers. That the only “compliment” Chae-young utters comes in this discussion highlights both this concept and all the aforementioned. Lastly, the documentarian also follows the two women after Chae-young moved to Brisbane, with a second round of discussions shedding even more light to their relationships. (Panos Kotzathanasis)

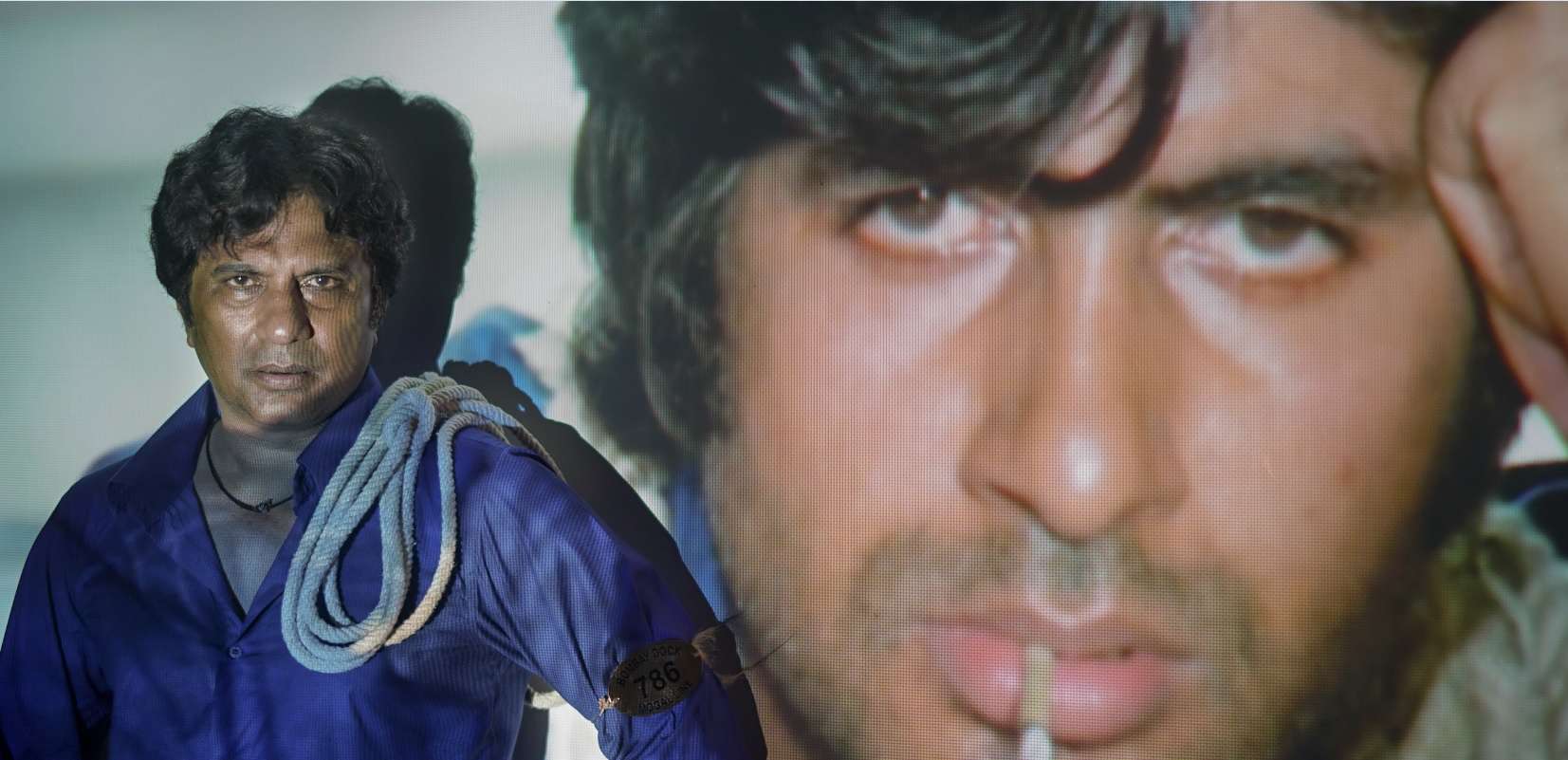

4. A.K.A (Geetika Narang Abbasi, India)

The three portraits she presents are quite thorough, as she managed to earn their trust to the point of going inside their houses and including their families in the documentaries. At the same time, the film presents an insider's look of Bollywood, from a perspective that is, probably, unprecedented. In that fashion, and with their stories intermingling, Abbasi interviews them on how they got into the particular business, how they managed to make a career out of it, their relations with the actual stars, their present, and even their future, thus rounding up a very detailed examination.

5. I am a Comedian (Fumiari Hyuga, Japan)

Evidently, having won the utter trust of Muramoto, the documentarian stays rather close to him, both his professional and personal moments, who eventually are revealed to be utterly intertwined, as his life experiences dictate his comedy, to the point that events like his father's death become part of it. It is this sincerity and in-your-face-attitude, along with the ability to turn such dramatic events to comedy, that is what essentially allows Muramoto to stand out, while making his portrait so captivating. The same applies to his insistence to his belief that laughter can change the world, as much as his portrayal behind the stage, who is eloquently revealed as one of depression and probably alcoholism, for which making people laugh seems to be the only medicine. (Panos Kotzathanasis)

6. Dark Red Forest (Jin Huaqing, China)

Jin Huaqing chooses to forego two of the mainstays of documentary filmmaking, the interview and focusing on a main subject, and instead adopts a much more observational approach in which his camera jumps from a subject to another, watching each nun carry different tasks such as cooking and studying to visiting the doctor and getting dharma lectures by a monk sitting offscreen. A reason for the decision to follow numerous people as opposed to one might have been the nuns themselves, who might have not wanted to be followed by a camera for long periods of time and have their practice hindered or possibly something else. We are never told and it doesn't matter because it works for a great advantage of the film, showing us the communal aspect of the nuns' lives. After all, they are all in the monastery complex striving to penetrate the Buddha's teachings and transcend the ego and the egocentric view of the world. And what more egocentric is there than having oneself be the focus of an entire movie? (Martin Lukanov)

7. Blue Island (Chan Tze Woon, Hong Kong)

Chan also presents glimpses of the current life in the megalopolis, including ones from musicians, hospital workers, legislators etc, while a number of scenes highlight the beauty of the city, particularly regarding the sea and the way it shapes the whole frame of the city. In that regard, Szeto Yat-lui's cinematography emerges as impressive, in the way he manages to depict all these different elements, with the same applying to Chan's own editing, which implements a rather fitting, relatively fast pace. On the other hand, it should also be noted that the hybrid approach can be confusing at times, while the dramatization parts do not work that well, even if the message gets through from the movie as a whole, resulting in a documentary that is occasionally, unnecessarily artistic. This, however, is but a small issue which could be perceived differently depending on one's state, and the movie as a whole emerges as informative, well-shot, and definitely brave, which is where its true value actually lies. (Panos Kotzathanasis)

8. Boundary: Flaming Feminist Action (Yun Ga-hyun. S. Korea)

In “Boundary: Flaming Feminist Action”, Yun Ga-hyun chooses to use a pretty minimal technical palette. The majority of the movie consists of interviews with the three women who sit in front of a white background. Though each of the three is interviewed separately, it seems to be done with the other two standing behind the camera (at one point, we seem to hear the voice of one of them, and a sweet credit scene in which the three of them take photos with the director). The interviews are interspersed with footage of protests and other activities organized by them. There are also some media footage from protests, but it is not much, and it is mostly about the earliest chapters of their history. After that, the media forgets about them, except when the women organize events they considers scandalous, such as when they protest against the fetishization of the female body by showing their breasts. The media, just like most men in Korean society, objectifies them and uses them however they sees fit. (Martin Lukanov)

9. Education and Nationalism (Hisayo Saika, Japan)

The presentation of the whole concept is as realistic as it is shocking, with Saika having done a rather thorough investigation, while managing to include interviews with members of both sides. At the same time, she pulls no punches in her comments, openly talking about political pressure, direct government involvement, and revisionary tactics that derive from the members of the “Abe group” who seem to have taken key positions in all hierarchies of the Japanese system. At the same time, and although not clearly answered, the question for the reasons for all these actions, which essentially aim at people forgetting the blights of war, also gets a reply here: The current government wants Japan to be able to go to war once more. (Panos Kotzathanasis)

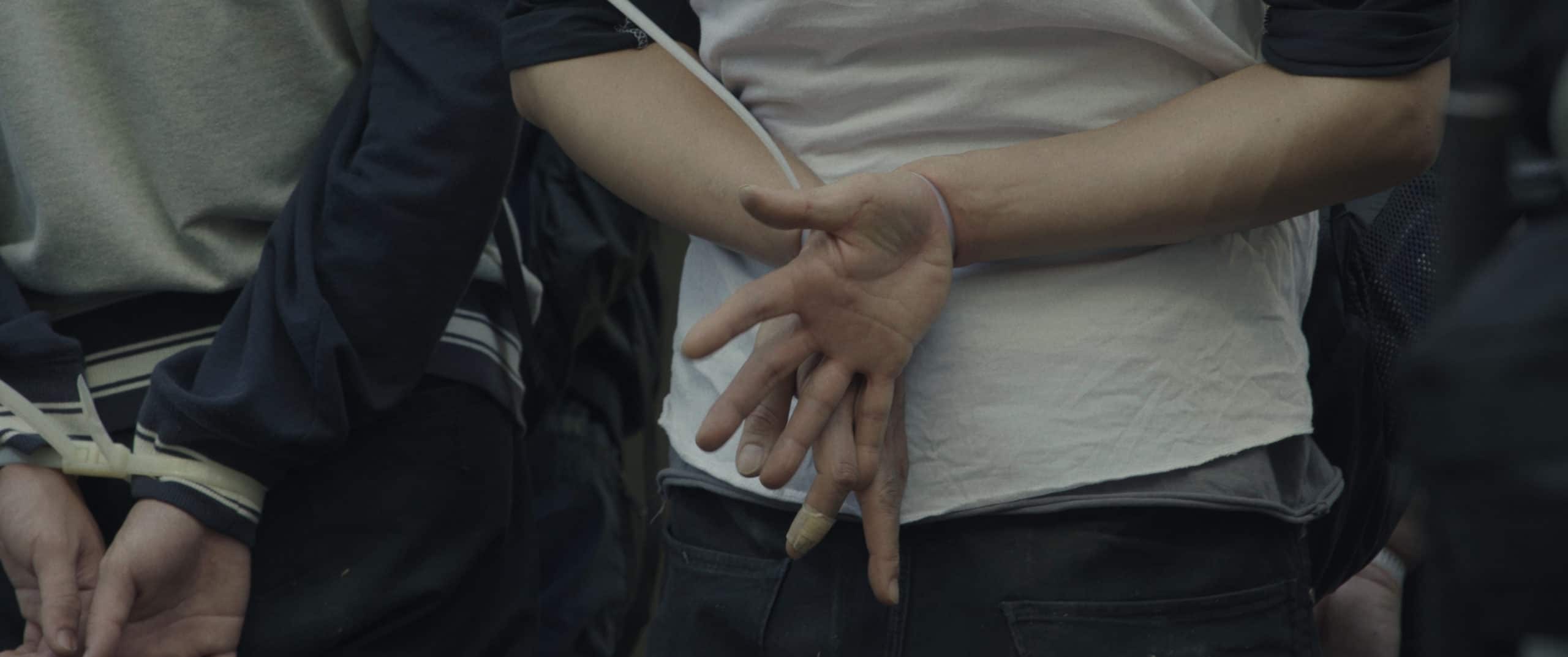

10. Children of the Mist (Diem Ha Le, Vietnam)

Rather than a study of a minority, “Children of the Mist” presents the viewer with an intimate and, what is more important, compassionate portrait of the relationship between a director and her subject. As the movie progresses, so does the relationship between the two women. This shows especially towards the end when Diem, with camera in hand, rushes to save her dear Di. She not only films as an observer to the goings-on in the family, but does everything she can to help the young girl. She urges Di's father to go and save his daughter when Vang kidnaps her. The father, drunk again, says he shouldn't meddle in the youth's life. And neither should she, his stern look suggests. She does the same, but to an even larger degree, when Vang and his family try to really kidnap the unwanting Di from her house. Ignoring her pleas and wriggling, they pull her towards their house, while the girl's parents sit idly, watching. Diem is the only person who rushes to help, trying to hold her friend, weaken the grasps of the invaders. Yet, she is almost attacked by none other than Di's father who looks like he is going to beat the director up for trying to help his daughter. (Martin Lukanov)

11. All That Breathes (Shaunak Sen, India)

Unlike “Midwives,” however, “All That Breathes” is carefully crafted. Sweeping vistas of the open, but polluted skies expound upon the cured kites' freedom. Off-kilter long shots deliberate upon whispered conversations behind doors. A plethora of pans complement Saud and Shehzad's voiceovers, each of which almost feel more poetry than they do prose. Sen's fascination with the collision between the animal kingdom and city is clear. The camera gazes in awe upon the sheer force of urbanity in the Indian capital – and nature's ability to adapt accordingly. (Grace Han)