135. Hwang Jin-ie (Bae Chang-ho, 1986)

Bae Chang-ho directs a naturalistic film, which moves quite slowly, in order to allow the spectator to enjoy Jeon Il-seong's impressive cinematography, who presents a number of rural and bucolic setting of extreme beauty, through a plethora of long shots. This tactic extends to the set design, costumes, music, and in general the depiction of the era, which is as realistic as possible. Most of all, it extends to the presentation of Jin-ie, with Chang-ho frequently using close up shots of Chang Mi-hee's impeccable face, again allowing the spectator to enjoy the beauty on screen.

The style of the film follows the rules of the art-house, with Kim Hyeon-I's editing implementing a rather slow pace, through a number of lengthy scenes, while the dialogue is scarce, with the actors mostly presenting their feelings and psychological status through their eyes and body stance.

136. The Surrogate Woman (Im Kwon-taek, 1986)

Im Kwon-taek directs a harsh Joseon (melo)drama that has the distinct purpose of criticizing the concept of surrogacy, which is still at large in S. Korea, although highly unregulated (it is only illegal when financial exchange is involved). The purpose and the central meaning of the film can be synopsized in the words of Ok-nyeo's mother, who, at one point, states, “We're not human. You're not a human just because you look like one. You're only human when you're treated like one”. This phrase embodies the way surrogate women were perceived at the time, in essence as birth machines, with the way they were picked and “trained” to conceive boys not having much difference than the way cattle are treated.

At the same time, Im criticizes the patriarchy and the superstition that ruled people's lives at the time, and still do to a point, highlighting the fact that all protagonists are actually victims to the rules. Through both aforementioned comments, and on a broader level, the film also presents the hardships and pain women had to endure, in a life that gave them very little free will.

137. Ticket (Im Kwon-taek, 1986)

Im Kwon-taek directs a rather dramatic film, which, this time though, does not fall into the trap of the melodrama, instead retaining a realistic approach, at least for the most part. The girls seem to exploit men, by selling them an illusion of appeal, but they too are exploited, mostly from the people whom they love. In that fashion, Im seems to blame men for the situation these women find themselves in, essentially presenting them as petty, vindictive even cowards occasionally. The clash between the two sides is inevitable, and violence eventually takes over, with the women being mostly on the receiving end. The finale, however, somewhat changes this perspective, although only for a little while.

As the film deals with prostitutes, Im could not but include elements of sensualism, benefitting the most by the appearance of the female cast. In the end, however, drama is the one that dominates the narrative, putting all other elements in the background, highlighting the misery of the profession in that fashion.

138. Our Joyful Young Days (Bae Chang-ho, 1987)

The two parts work quite well in combining almost every popular aspect of commercial cinema, but I felt that the second part is somewhat weaker, both due to the far-fetched development (which combines “happily ever after” with melodrama), and the fact that it extends the duration of the movie to over 2 hours, thus making it a bit tiring. Kim Hyun's editing tones down this essence, though, with him implementing a relatively fast pace, that stresses the entertainment aspect of the film.

In this, highly commercial setting, Bae still managed to include some social comments, mostly revolving around the previous (at the time) generation, which is personified in Yeong-min's father, in another, quite good performance, this time from Choi Bool-am, and his friends. Bae presentation in that regard is almost harsh, with the father portrayed as a drunkard, ignorant, who could not understand the changes that came, and forced his dreams of financial success to a son that had to follow his “instructions” due to filial piety, thus deeming him, in essence, infantile. This tactic is the one that makes Yeong-min indecisive, timid and in conclusion, adrift in life. This comment is given mostly in humorous and subtle fashion, but the impact remains, in one of Bae's direction best assets.

139. Hello God (Bae Chang-ho, 1987)

Much like “Whale Hunting”, Bae Chang-ho directs a road film of episodic nature, which combines comedy and (melo) drama in a rather entertaining, but also a bit shallow package. Min-woo's shenanigans are quite funny, even when they fail, but in the end, they also end up being dramatic, with the sequence in the restaurant being the apogee of this tendency. Ahn Sung-ki as Byeong-tae plays the part in understandable fashion, but his performance lingers towards aloofness rather than the dramatic, particularly because the people he and the group meet do not seem to understand that he is sick. Perhaps this could be interpreted as a comment on the lack of providence, both by the state and people regarding this illness, but the message (if it exists) is quite toned down.

In this road trip, some of the events seem to be on the border of reality (and logic) and occasionally surpassing it. The one where an in-labor Choon-ja is crossing a river with Byeong-tae, in pouring rain and eventually reaching a house where only children present, and having to give birth in a barn is the most significant testament to the fact, in a sequence that seems to draw inspiration from the birth of Jesus. The finale, which satisfies the need of the audience for a shappy conclusion is also somewhat illogical, although in entraining fashion.

140. Sa Bangji (Song Kyung-shik, 1988)

Song Kyung-shik directs a movie that includes almost every favorite aspect of Korean audiences, with the melodrama, the episodic structure and the odyssey-like story moving towards a distinct crowd-pleasing path. At the same time though, there are two elements that make the movie stand completely apart from almost any other local production. Obviously, the first one is the main character, with this probably being the first time an hermaphrodite is the protagonist of a Korean movie. Song highlights the difficulties her life presents as soon as people discover her true identity, with words like ‘ monster ‘ and ‘abomination' setting the tone quite eloquently here, with the drama emerging mostly from this root.

The second is the erotic, which begins as simple sensuality before it becomes more and more steamy, with the sex scenes following a homosexual path, which can also be perceived as a comment regarding the subject, particularly during the era. The way these scenes change as the story progresses is also interesting, as the artistic first ones soon give their stead to more titillating ones, with the last pointing somewhere close to soft-porno, despite its briefness and lack of nudity. Also of interest is the less-than-a-second one that presents Sa Bangji's member, in a moment that definitely remains on the mind of the viewer.

141. Gagman (Lee Myung-se, 1988)

The episodic narrative of the film, that seems to revolve around the “cinema imitates life and vice versa” concept is rather unusual, dominated by elements of slapstick and absurdness, all the while retaining a sense of disorientation due to the thinning of the borders between fantasy (cinema if you prefer) and reality. Through this tactic, Lee makes a number of comments regarding the movie industry, with his most obvious (and most ironic) being the one when the director exclaims, “Who would make a real movie in the 21st century?” However, the gag-humor that seems to dominate the film (the scene where the girl is singing Suzie Q on stage and the director and the barber dance is a great sample, and one of the most entertaining sequences in the film) allows the story to flow quite nicely, particularly because Lee does not seem to take himself and his movie overly seriously. This flow benefits the most by Kim Hyeon-I's (another Bae Chang-ho regular) editing, who connects the various scenes with artfulness, while retaining a rather fast pace that suits the film's aesthetics perfectly.

Another central point in the narrative is the characters and their connection, which revolves around the ability of Lee Jong-se to draw the other two into his fantasies. And if the barber, who also represents the eagerness Koreans felt at the time for anything American, was keen to do so from the beginning, the way the street smart Seon-yeong falls under his spell is impressive, with him drawing her in gradually, through his rather appealing paranoia.

142. The Age of Success (Jang Sun-woo, 1988)

Jang Sun-woo presents a critique of the extreme capitalism that was permeating a Korea that was handling the Olympic games at the time, where the continuous financial progress had made the pursuit of sales, and subsequently money, a one way street for a plethora of people. The tactics the company used in order to overcome one another are satirized in the most hilarious but also pointed way. The continuous increase of price off in products in convenience stores, the sexualization of the advertisements, the inclusion of technology that seems at least far fetched are just a few of the tricks presented here, essentially presenting the corporate men and their tactics as utterly ridiculous. The behavior of the higher ups, and their demand for constant results no matter what, is also presented under the same prism, essentially deeming all of them as hateful, and quite sad caricatures, even if the “sadness” gets bigger the lower one is placed in the corporate ladder.

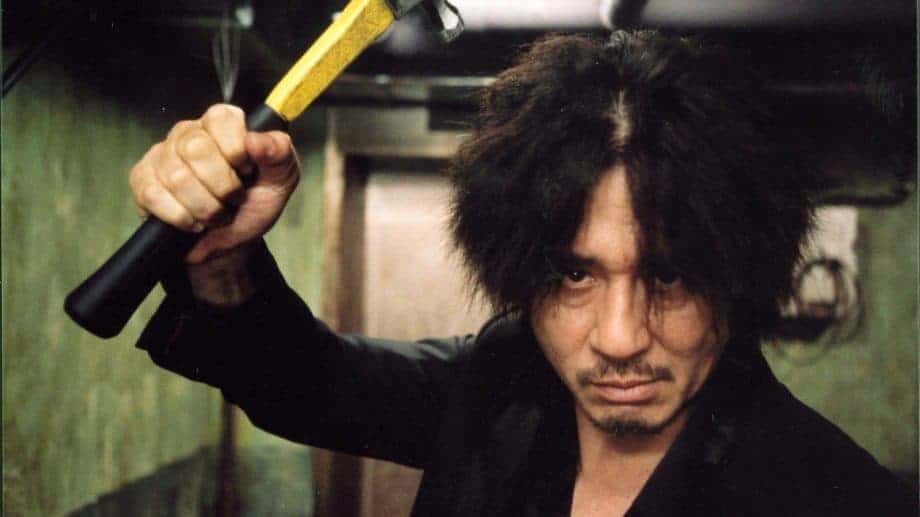

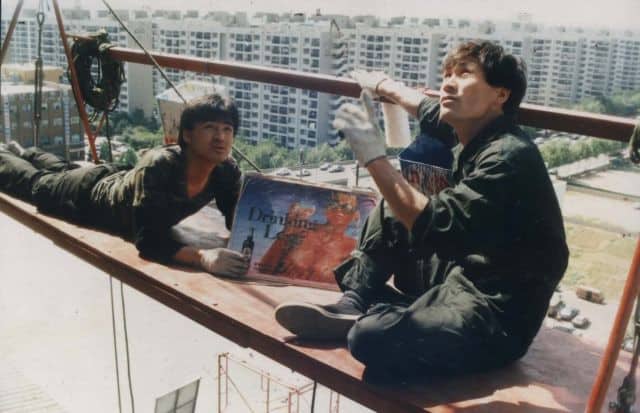

143. Chilsu and Mansu (Park Kwang-soo, 1988)

Park Kwang-soo directs a film that uses an unlikely base, since the way the two become friends borders on the surrealistic (one can easily see the impact the film had on Kim Ki-duk's “Bad Guy”) in order to present a number of sociopolitical comments about the era, which become much more intense as the story progresses. In that fashion, initially the film deals with the turning of the Koreans towards western civilization and particularly the US (English language, movies, clothes, video games, music, and almost every aspect of the then American pop culture), and the newly realized social inequality and worker's rights, as expressed in the scene where Man-su quits. As the story progresses though, the comments become more “serious” and intense, regarding the practices of the then regime towards political dissidents, which even extends to their children, as we witness in Man-su's life story. The impact of the US is represented by Chil-su's life , regarding both his family's story and his will to move to Miami.

144. Black Republic (Park Kwang-soo, 1990)

Park Kwang-soo directs and pens an intensely bleak film, where hope is nowhere to be found, neither for the workers and the women, who form the lowest ranks of the society depicted, nor the privileged of the new generation. The setting of the filled with dust and dirt mining town, serves his purpose quite adequately, with Yoo Young-gil's cinematography highlighting this bleakness, both in the “foggy” exteriors and the dark interiors, with a very fitting approach. In essence, the town is a metaphor for the Korean society of the time (to say the least), where the lowest ranks (as mentioned above) are almost constantly subjected to oppression by the authorities and the “capital”, with their disillusionment about the fact playing absolutely no role in their circumstances. In this setting, love seems to provide a thin ray of hope, but even this does not last for long, as the inevitable violence resulting from reality, eventually erases even this minor optimism, as depicted, quite eloquently, during the finale.

145. Our Twisted Hero (Park Jon-won, 1992)

Yi Mun-yol's book was highly political, even through its metaphorical approach, and although Park Jong-won's movie follows the same path, it also includes a number of episodes that seem to aim at entertainment and in general to lighten the narrative, with the concept of the students peaking at the female teacher and the train rails challenge being among the most notable samples.

Nevertheless, the metaphor is still well-presented and quite impactful. Om Sok-dae is the embodiment of the dictatorial regimes of S. Korea, and Byeong-tae the powers of resistance that tried to overthrow them and failed. The former rules with a combination of hard and soft power, which uses the fact that he is the biggest and strongest student in the classroom in order to establish fear on the rest of the students and rule through the potential consequences to any who does not bid his will. The fact that he does not rule through just brute power, which would eventually draw the attention of the teachers on his practices, but through the aforementioned setting of fear and through cunningness in the very few times Byeong-tae manages to somewhat put him on the spotlight with his teacher, is a testament to how dictatorships work. The same applies to Seok-dae's behaviour after Byeong-tae succumbs to him, which is a perfect representation of the carrot and stick tactic.