During the last few years, and after an instigation of my friend Bastian Meiresonne (who never forgets to stress the fact btw), I have tried to watch and review as many films from the Korean Film Archive as possible, starting from the oldest ones. The result is 150 reviews, a sample of each you can find in the list below. The full articles have been published on Hancinema. Some of the films are no longer available, since the rights were bought and were released in physical form (Blu-ray, DVD etc) but most of them you can find in the particular channel. The list will be updated

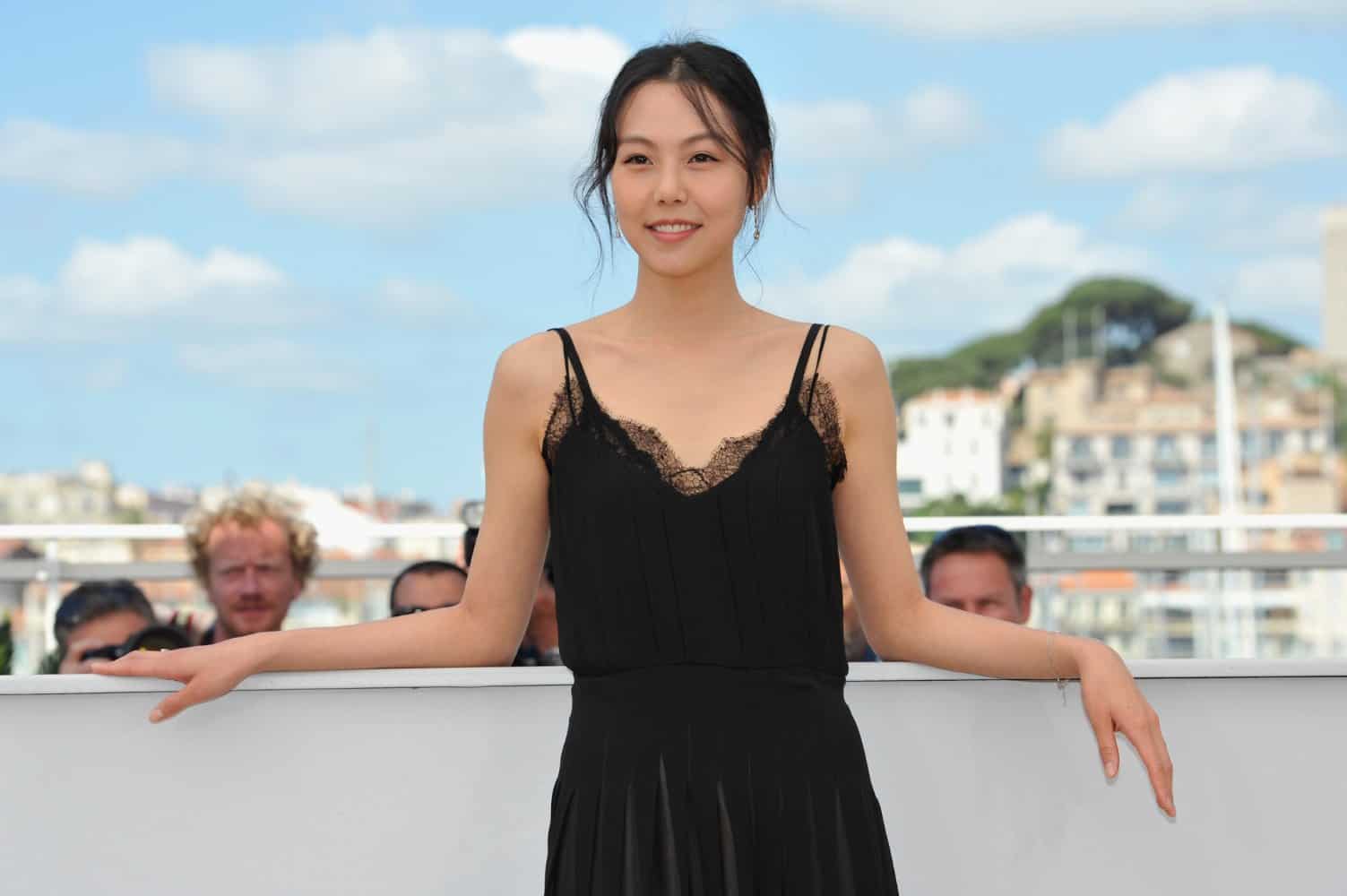

1. Sweet Dream (Yang Ju-nam, 1936)

Let me start with the obvious. The Japanese influence in the film is everywhere to be found, from the subtitles on the right of the screen, to the clothes in the shop Ae-soon visits, to a performance in a theater Lee Seon-ryong visits with his daughter. Apart from this, the film has the distinct purpose of highlighting the “rules” all wives should follow, particularly regarding their obedience to their “man”. In that fashion, Yang Ju-nam aims to depict the consequences of Ae-soon's irrational behaviour, both on her and on her family. The fact that the story reveals her as a truly promiscuous woman, stripped from any kind of devotion to any man, also moves towards the same path, as is the case with the tragic events that fall upon her daughter. Of course, criticizing this kind of depiction of women during the 30s would be futile, but is still quite shocking to watch how women were perceived at the time. Furthermore, an effort to show that people should abide by the laws is equally evident if a bit more subtle, as depicted in both the fighting scene and the one where the driver of a car refuses to drive faster in fear of breaking the law, and the consequences of when he actually does, which are dire.

Aesthetically, the film is quite melodramatic, with Choe Dok-gyeon's script using sentimentalism through a number of extreme occurrences in order to make the aforementioned concepts more impactful. The acting also follows these rules, with Yu Seon-ok's performance as Jeong-hee being particularly melodramatic and Lee Geum-ryong's as Jeong-hee following close after. On the other hand, Mun Ye-bong as Ae-soon is exceptional in presenting the vanity of a femme fatale, and her acting is definitely on a different level than the rest of the cast.

2. Tuition (Baek Un-haeng, Choi In-gyu, 1940)

Choi In-gyu and Baek Un-haeng direct a low-budget film that moves mostly in melodramatic paths, along with the aforementioned subtle but eloquent propaganda elements and a small part that functions as a road trip, when Yeong-dal decides to visits his aunt. The house, particularly after the grandmother falls ill is the main source of the melodrama, as we watch a young boy who longs to see his parents and go to school not being able to do either, or to help the only relative he has left. The Korean (he could not be Japanese, we will go back to this point in a bit) house owner functions as the villain in that regard, as he not only threatens to kick out an old lady and small kid but also has no regrets in getting Yeong-dal's tuition money from him. On the opposite side is the Japanese teacher, who functions as a benevolent force both in his profession, genuinely caring for his students, and as an actual person, as we see him willing to help even outside his capacity. This contrast between the “evil” Korean land owner and the benevolent Japanese teacher is one of the main sources of propaganda in the film. Furthemore, the directors also took care of portraying the school environment, which is run on Japanese values (and in the Japanese language) as a truly idyllic place, the only source of solace for the troubled young boy. Lastly, the fact that Yeong-dal sings Japanese military songs while on his trip cements this tactic

The presence of Kenji Susukida in the role of the teacher falls under the expansion efforts mentioned in the prologue, although I have to say that Susukida is quite convincing as a constant source of virtue. The one who steals the show however, is Cheong Chan-jo as Yeong-dal, who manages to portray a number of feelings and psychological statuses ranging from frustration and despair to longing and enthusiasm in the best fashion. Kim Jong-il-II as Jeong-he is also quite good in her part, functioning as a great “sidekick” of the protagonist.

3. Spring of Korean Peninsula (Lee Byung-il, 1941)

Lee Byung-il follows the rules of the melodrama, which, in combination with the presence of the always popular for nationalistic reasons “Story of Chunhyang” (plus the fact that costume-dramas were always popular in Korea) end up in a very entertaining film that was bound to be a commercial success in the country. Furthermore, the presentation of the film-within-the-film is excellent, also highlighting Yi Young-woon's editing, as is the depiction of the era and the circumstances of the movie industry and everyday life overall. This last part benefits the most by Yang Se-ung's cinematography, who succeeds in portraying the many different settings of the film (from film sets and studios to houses and even the police precinct) with artistry and realism.

However, it is in context that the movie really thrives, since the comments Lee Byung-il managed to include are many, intricate, and diverse. The inner problems of the movie industry at the time are the most obvious, with the lack of funding, the frictions between the directors and the stars, and the fact that co-producing with the Japanese was a one-way street, also for the “need” of the Japanese to be portrayed as some kind of heroes that save the day of the poor Koreans. In that last aspect, and although Lee seems to mention the presence of the Japanese (the movie included both Japanese and Korean (subtitled) dialogues) as something beneficial for the industry, he also makes a point of highlighting that the fact was not exactly “approved and accepted” by local artists. This comment had to be subtle, due to the Film Law, and Lee did a great job of depicting in exactly that fashion, mostly through small details or brief scenes featuring the director. The scene when the Japanese owner of the new film company announces in all glory that the new endeavors will focus on highlighting Korean and Japan as one nation has most of the members happy, but not all of them, with particularly the director being concerned rather than joyful. The fact that the equipment the Japanese movie studios have was not available to Koreans who had to struggle even in the co-production level is also mentioned, while the last scene, with the director's visage, also moves in that direction, with the character actually mirroring Lee himself throughout the story.

4. Hurrah! For Freedom (Choi In-gyu, 1946)

Choi In-gyu directs a film that uses a kind of love triangle and action/spy movie premises, in order to present his political comments. The hate for the Japanese and their Korean collaborators permeates the narrative, but one can also find harsh critique on the intellectuals, and particularly those who were keen to think instead of act against the occupation forces. This comment becomes quite evident in a scene where the cell members meet, only to end up facing the “wrath” of Han-joong who accuses them of cowardice and inactivity; although in the end, he makes a point of mentioning the significance of their participation in the resistance. In that very politically dictated setting, it is ironic that most of the scenes removed actually involve Dok Eun-gi who plays the traitor Nam-boo, whose parts were cut because he was one of those who defected to the North after the Korean War.

Nevertheless, another very interesting point is the role of women, who in this case, are instigated not only by love but also from patriotic sentiment, and furthermore, take action, and play a significant role in the finale regarding the escape of prisoners.

5. The Night Before Independence Day (Choi In-gyu, 1948)

Choi In-gyu directs a movie that seems to want to show as many aspects of Korean society of the time, and to unite all of them under the newly formed government. In that fashion, the story entails criminals, murderers, rapists, drug addicts, gambling, the police, the haves and the have-nots, and a number of other individuals, whose stories eventually are proven to be connected. This, interconnecting, episodic nature of the film may defy current-time logic on a number of levels, but actually carries the film for its most part. I say, “for the most part”, because the ending with Min-ka's complete turn-around borders on the ridiculous, as is the case with the mountain walk.

Due to the bad quality of the film and the evidently low-budget of the production, I would prefer not to dwell too much on the technical aspects. The only thing I would like to mention is that Hong Seong-ki's editing is quite good (considering) with him implementing frequent cuts that give the film a good rhythm and pace overall. Choi Yeong-su, who voice-acts all the parts and narrates initially seemed quite strange to me, particularly when he did the female parts. However, as the movie progressed, I got used to him, and the fact that he voices without any particular exaltation is definitely a tick in the pros column. I also have to note here that the movie is not a silent one, since sound and music are heard, something that made the experience of having a pyonsa even more surrealistic.

6. A Public Prosecutor and a Teacher (Yun Dae-ryong, 1948)

Evidently, and on a logical level, the story (which is based on a novel by Kim Choon-gwang) appears completely absurd, with Yun Dae-ryong presenting a number of unlikely occurrences whose sole purpose is extreme sentimentalism, and subsequently, melodrama. In that fashion, the events that befall Jang-son in the first part and Yang-chun in the second just keep getting worse, in a comment that seems to state how unfair the world is, and that no good deed goes unpunished. And although the ending provides an element of catharsis, the occurrences that lead there are too farfetched for it to have the impact of a Greek Tragedy for example, with the way Yang-chun's husband dies being the most hyperbolic.

On the other hand, the few moments of “action”, specifically the sequences revolving around the fugitive are quite intriguing, as we watch him hiding in the fields, climbing the roof of Yang-chun's house or avoiding the police with her help, with the part even emitting a sense of agony about what is going to happen, while also presenting some noir elements.

7. A Hometown in Heart (Yun Yong-gyu, 1949)

Yun Yong-gyu directs a genuine melodrama, about a boy whose life is in shambles, and every ray of hope seems to clash with his harsh reality, repeatedly. The events may be a bit far-fetched (at least when one watches the film now) but the relationships presented in the film work quite well actually, adding to the entertainment it offers and making a number of social comments, regarding motherhood, family, loss, and tradition versus modernity. The strict head monk's presence functions as the catalyst for the progress of the story, in all the connections Do-seong seems to have: with Eun-hee, his real mother, even the handyman and the rest of the children. At the same time, and particularly through the unexpectedly optimistic finale, the head monk also functions as the driving force for Do-seong's path towards maturity.

This part also made me think that the film could be perceived as a metaphor for S. Korea's future in 1949, when the film was screened. In that regard, if we consider Do-seong as the personification of the then young S. Korea, Eun-hee, with her modern ways and beauty could be a metaphor for the US; the biological mother who abandoned her son, the united Korea of the past; and the monk, tradition and religion, who provided a temporary solace for the troubles the country had to face during and after WW2, but in no way a permanent solution. The finale seems to present the answer the director suggests, although the fact that there is no concise ending, leaves the outcome of this decision quite open.

8. A Bouquet of Thirty Million People (Shin Kyeong-gyun, 1951)

Being shot in the middle of the Korean War, Shin Kyeong-gyun obviously did not have the equipment that would allow him to shoot any kind of intricate scenes, and in order to present the war, he included documentary footage in the narrative. However, despite the technical limitations, his comments about the blight of war are rather eloquent, with the difference between the initial setting and the one during the war highlighting this notion in the best fashion. At the same time, by implementing various non-war scenes during Geon-yeong's days in the hospital, of little girls dancing for example, he succeeds in toning down the drama, in a much needed “trick” considering the nature of the film.

More than anything however, and due to the eventual sacrifice, the movie emerges as an ode to motherhood, a concept, which when combined with the title, points towards the mother of all the 30 million residents of Korea, essentially the country itself, in a rather intricate metaphor.

9. The Hand of Destiny (Han Hyeong-mo, 1954)

Han Hyeong-mo directs a film in three parts, each of whom seems to be of a different genre. In that fashion, the film starts as a romance, continues as an espionage thriller with much action, and concludes as a melodrama, although the latter element actually permeates the film. Han's approach to his subject, however, is quite minimalist, since the two protagonists are almost the only ones that appear on screen, and the rest of the cast get very few lines, almost exclusively without revealing their faces. This tactic extends to the production values, with the majority of the images in the film just showing the two protagonists interacting with each other, with the sole exception of the few action scenes, which are the only that take place in a non-urban environment. Lee Seong-hwi's cinematography is quite good in this setting, particularly excelling in the framing of the two characters and the way he avoids revealing the faces of the rest of the characters. Han Hyeong-mo's own editing changes for each part, with the romantic and the melodramatic parts mostly comprising of relatively lengthy one-shots, and the action of many, rapidly changing cuts. Both tactics serve the respective genre's aesthetics quite nicely.

10. The Widow (Park Nam-ok, 1955)

Park Nam-ok presents a rather invigorating story, which, finally, presents women in the urban setting as in charge of their own fate and not just the recipients and/or carriers of tragedy for them and their families when they decide not to follow the rules of Confucianism. In Park's world on the contrary, the women are those who manipulate the weaves of fate, with the men, in essence, being puppets to their will.

The film begins as a distinct melodrama, with the scene with the daughter walking to school introducing the concept quite eloquently. However, and despite the fact that Joo's arc moves towards the melodrama for the whole of the movie (at least the part saved), the narrative soon becomes more erotic, with the quartet shaped by Sin-ja, Lee Seong-jin, Mrs. Lee and Taek providing the main arc of the story. This aspect is what sets the movie apart from many productions of the era, but it is not the only. The subtle but eloquent elements of eroticism are also unusual for the time, with the scenes at the beach (particularly Taek caressing Mrs. Lee's legs) and the sequence in the hotel where the four meet, being unusually bold in their implications. Furthermore, the presentation of Sin-ja firstly as a human being (with all her faults and virtues) is also quite unique, since the character escapes the Confucian archetypes that want women to be only daughters, wives and mothers. Sin-ja is nothing of the first two, and the way she dismisses the third capacity is almost shocking. At the same time, however, Park also highlights the fact that women at the time were forced to rely on manipulative behaviour to survive in the male-dominated society, in a rather disillusioned and highly realistic comment.

11. Piagol (Lee Kang-cheon, 1955)

The public and the authorities may have criticized the film for the humanization of the North Korean partisans, but seen in retrospective, the film is anything but pro-communist. The members of the band are portrayed as filled with faults, both as human beings and as soldiers. The love triangle (and the addition of So-joo) is probably the harshest element in that regard, particularly since General Agari is presented as a true satyr, a man who uses his authority to have sex, with the fact that he is eventually turned down by Cheol-soo being another “nail in his coffin”. Agari is actually the main source of anti-communist propaganda, since he is portrayed as overly proud, cruel, completely unforgiving, having almost no control over his troops apart from when he kills them, and in essence of being the only one who does not understand the situation. The fact that Ae-ran is portrayed as smarter, more down-to-earth and in essence more loyal, could also be perceived as a kind of mocking towards him.

These two characters are the most memorable in the film, with Lee Ye-chun and Kim Jin-kyu giving excellent performances, respectively, while their antithetical chemistry is one of the best elements of the narrative.

The critique, however, does not stop here. Cheol-soo, who seems to function as a metaphor for communist intellectuals is portrayed as timid, inactive, and constantly lost in thought despite the direness of the situation, an in essence unable to do the slightest thing even when his life is in danger. Furthermore, the practices of the group, and particularly the attack on the village who is ordered by the High Command, also present a propagandistic comment about communist practices, while the fact that many soldiers kill old people with no remorse, since the higher ups deemed them counter-revolutionaries, is probably the harshest comment presented in the film.