Santosh Sivan, a filmmaker from Kerala, is one of the greatest modern cinematographers from the

Subcontinent. He has never restricted to just the Malayalam language area and worked on films in

Tamil, Hindi, and others. He is remembered for his fantastic collaboration with Mani Ratnam on such

movies as “Dil Se”, “Iruvar” or “Roja”. Quite early in his career, he also took the helm of the director.

He delivered various projects, some of which were recognized in the festival circuit (“Malli”, “Terrorist”,

“Navarasa”, “Tahaan”), and some were epic blockbusters with a multistar cast (“Asoka” and

“Urumi”).

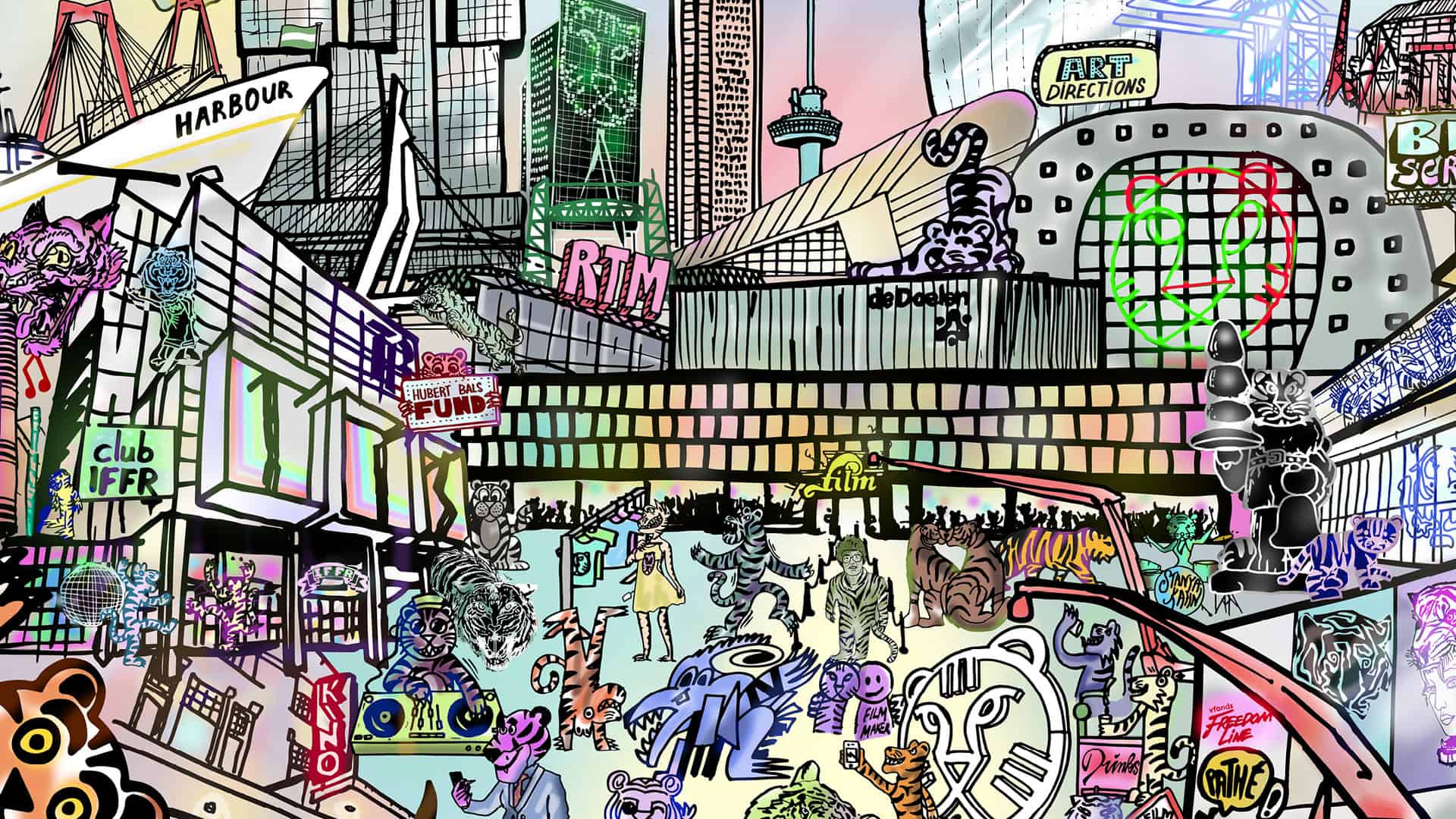

Moha is screening at International Film Festival Rotterdam

“Moha” is his latest directorial venture, obviously created with the festival audience in mind. It

detaches from conventional narrative storytelling and differs from the other films by Sivan-the

director (though not in terms of visuals, his camerawork is a trademark). Slightly it may resemble

“Navarasa”, which was contemplative and very experimental in form.

There are no dialogues in the movie, but it introduces the omniscient narrator, the one we well know

from literature, who reports the events and comments on the characters' choices. The rest we read

from the protagonists' body language and facial expressions, sometimes accompanied by sounds

(like whistling by the main male character). In a way, it refers to old traditional dance and theatre

forms using gestures as the main mean of communication with the audience. Like these forms, it

doesn't rely on silence, and movement is driven by the music. In the absence of dialogues, sound

becomes very important, be it the moody and traditionally-influenced background music or the

voices of nature, like howling wind, flowing water, or chirping birds.

“Moha” is set in a mythical “long time ago” and shaped like a retelling of a myth, which suits the

chosen dialogue-less form and the presence of a storyteller. We can't discuss the plot much, as it is

just specious: the peace of a mysterious hermit (charismatic Jaaved Jaaferi) is disturbed one day by

a female-shaped being (Shaylee Krishen). Unfortunately, the film, which is drawing from the world

of symbols and philosophic systems, after the intriguing introduction, becomes more and more

blurry, hermetic, and lost in metaphors. It also relies on banal motives, like the female being a prized

possession and the subject of the power-driven rivalry of two males or earthly desires driving

someone away from the chosen path.

The title, “Moha”, is a term found both in Buddhism and Hinduism, and can be understood as an

attachment to worldly matters or as delusion and dullness. (Prajna the wisdom, insight is the

opposition). The narrator refers to “shakti”, which is the primordial energy of the cosmos, the female

creative, that is both creative, sustaining, and destructive. But the knowledge about those references

doesn't make the film more approachable or appealing. The depth of the tale becomes more and more

illusionary. However, the visual appeal still makes it worth a try, especially on a big screen. Even for

just one scene, with a nymph-like female moving, as if she was dancing, behind a sun-lit curtain. A

light and shadow play makes the curtain look like something of unique beauty, but with the beams

gone, it is just a torn piece of fabric.