Memories of the decades-long civil war are still haunting Sri Lankan society. Tourists are vacationing on paradise-like beaches and little do they know about the violent conflict between the Sinhalese majority and the Sri Lankan Tamil (Eelam) minority, which has claimed a huge number of victims (United Nations estimated up to 100.000 taken lives). The war has never been properly addressed by the international community. The most common narration is a black-and-white story about the Sri Lankan government fighting the terrorists of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE). The fundaments of conflict, such as long-time discrimination and marginalization of the Tamil minority, are not widely known. And while it is true that LTTE, advocating for a separate independent state for island Tamils, introduced tactics like suicide bombers attacks (including female-led ones) or the use of child soldiers (trained at special camps) and is responsible for assassinations of Indian prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi or Sri Lankan president Ranasinghe Premadasa, the war crimes of Sri Lankan government, including tortures of prisoners, unexplained disappearances of people, or casualties among the civilians, are denied or kept behind a veil of silence. The brutal, final stages of the war in 2009 resulted in heinous human rights violations and U.N. mentioned in a report that at least 40.000 of Tamil Civilians died during it (as a result of actions by both sides). Rebels prevented civilians from fleeing the last narrow strip of land, where the fights were taking place, and the areas named the “no fire zones” were ruthlessly and unlawfully shelled by the Sri Lankan government forces. The investigative documentary “No Fire Zone: In the Killing Fields of Sri Lanka” from 2013 is a reliable testimony of the events.

“Munnel” by Visakesa Chandrasekaram, a scholar, human rights lawyer, writer, independent artist, and film and theatre director, is one of the rare fair cinematic representations of the conflict. It doesn’t document the war itself or present the arguments of any of the sides. The director (also taking the role of a writer and a producer) tells about the aftermath of the devastating events and focuses on the human side of it. The movie is made in Tamil with a cast and crew recruited among the native speakers from the area, who all are, as we can read in the program description, “direct witnesses to the civil war”. It adds depth and a sense of authenticity to a fictional tale, which for sure is based on many factual reports and personal experiences.

Munnel is screening at International Film Festival Rotterdam

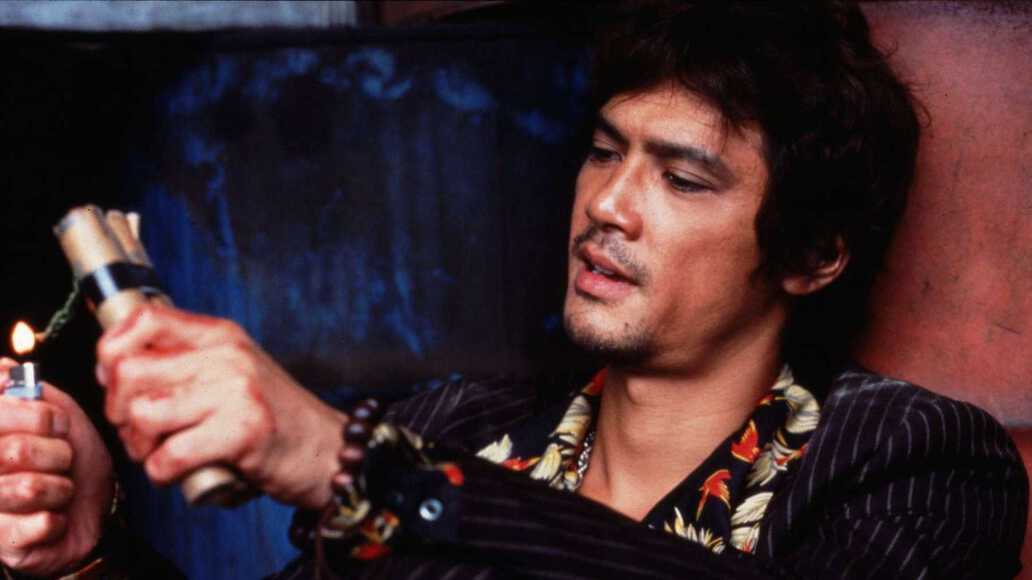

“Munnel” means “sand” in Tamil. This title seems out of place, maybe a bit poetic, but when we realize that during the fights beaches were soaked with blood, it becomes disturbing. Nature here, lush and still, is just a silent and helpless witness. The movie begins on the sand, where a man regains consciousness among the dead bodies. With a seriously wounded leg, he is unable to walk, and he crawls in a desperate attempt to survive. We also watch a group of refugees marching across the waters, carrying their modest possessions.

Fast forward, we meet the man, named Rudran, 5 years later. He is disabled, walking with a crutch, and is facing a trial for felonies against the Republic of Sri Lanka, accused under the section 17 of the Prevention of terrorism Act 1978, under section 17 of gathering intelligence on the military in order to carry out ambushes and for not providing information to the Government authorities on the LTTE actions. Despaired, crippled, and broken, he doesn’t seem a dangerous criminal. With the efforts of his lawyer, Rudran gets bail. He comes back home in Northern Province with his aged mother, who carries him on a junky bicycle. This display of fragility and vulnerability is a tearing picture. Rudran wants to find Vaani, his childhood sweetheart, with whom he lost touch after she got to a refugee camp. Many people are looking for their friends and relatives lost during the war, and Rudran’s mother, a respected soothsayer, is trying to help them with an aid of a merciful goddess.

Sivakumar Lingerswaran gives an impressive and layer performance. His silence and empty gaze tell more than a thousand words, and his body language is tremendous. Kamala Sri Mohan Kumar as his enigmatic, reserved mother, and Thurkka Magendran as Vaani are equally good.

The script doesn’t rely on a chain of events. It’s focused on characters and their relations and emotions, the past influencing and hunting the present, and the price paid by individuals. It combines accuracy and realism with a subtle poetic insight. The search for identity, and the struggle to overcome memories full of pain. It shows the process of coming back to normalcy after the trauma, the attempts to reclaim one’s life. The director talks about military checkpoints, ruined homes, bombed churches, and fear management when everyone can be taken away without any charges in the dead of night. He also talks about the tortures of war prisoners. In a very distressing scene, the doctor during the court-ordered forensic examination in a dry, professional voice narrates the number, size, nature, and cause of Rudran’s scars. “Healed” he also says, but we know that this kind of wound never heals.

But the movie is not a one-sided testimony of war atrocities. Rudran is an ambiguous character. A victim for sure, but he also hides his dark side. We slowly learn that he may be responsible for something unforgivable. Also, when he thinks of Vaani, these are not innocent reminiscences of a teen courtship. He mentions times, when they were both training at an LTTE camp, and recalls how she dealt with guns. In “Munnel” the world is not black and white. It’s dark, grey, and desperate for hope. A hope that seems more and more delusionary, when people don’t find consolation in religion or their old dreams. The old prejudices prevail, despite all the madness. There’s a scene when a father of a girl who suffered during the war rejects a boy interested in her, claiming that after all, their cast differences still exist.

Visakesa Chandrasekaram delivers a highly important movie. Its strength comes not only from the important subject but also from the director’s ability to find a proper form. His quiet, slow-paced contemplation, is filled with tearing melancholy. It’s not a documentary narration, it is an attempt to capture a post-war consciousness, a pain that keeps throbbing.