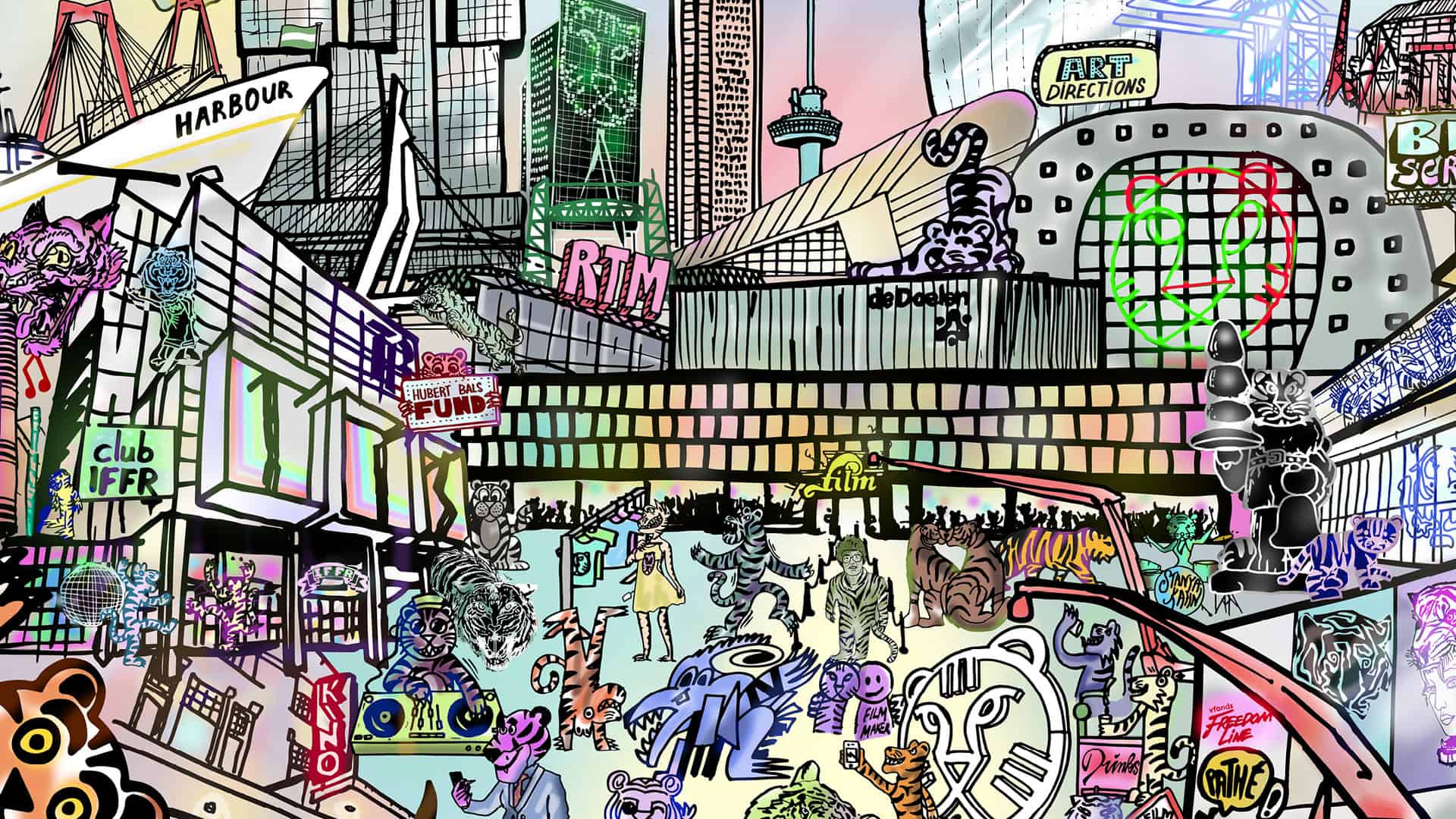

Initially a half an hour movie, which used nine existing films from 1952 to 1980 to reimagine, reconstruct, simulate, commemorate, and commiserate with the seventy-five lost Philippine silent films from 1912 to 1933, “Nitrate: To the Ghosts of the 75 Lost Philippine Silent Films (1912-1933)” now finds its final form in this 1-hour edition, which just premiered in Rotterdam.

While Philippine cinema has existed for decades, a lack of care and importance to the preservation of their film culture has unfortunately caused numerous titles from that period to be lost beyond recovery. Originally commissioned by Cannes-winning filmmaker Apichatpong Weerasethakul, Khavn assembled the main omnibus “Nitrate” to highlight the importance of preserving their culture and heritage with a collection of clippings of surviving genre films from that period.

In that fashion, the movie unfolds as a series of different footage from different movies, presented in different coloring each time, with red, blue, green, purple, and black-and-white dominating the images, and with a different sound approach, which includes various styles of music, narration, even the reciting of poetry. What connects the movies presented, is that all of them seem to be segments of horror titles, with graveyards, fires, ghosts, vampires, Ouija boards, hanged dolls, and knives with Jesus carved on them being the most memorable images in this collection of vignettes.

As such, and considering that new films are implemented to portray lost silent films of the past, a question quickly rises, regarding the reason people always liked to watch horror movies. At the same time, the movie, through the rather intriguing sequences presented, does raise interest regarding these films of the past, essentially fulfilling one goal of the archiving as a concept, with the inclusion of the titles before each part adding to this curiosity while helping the viewer who would like to explore more.

A number of kaleidoscopic images, various color grading “tricks”, and the overall play with image and sound conclude the cinematic approach of the film.

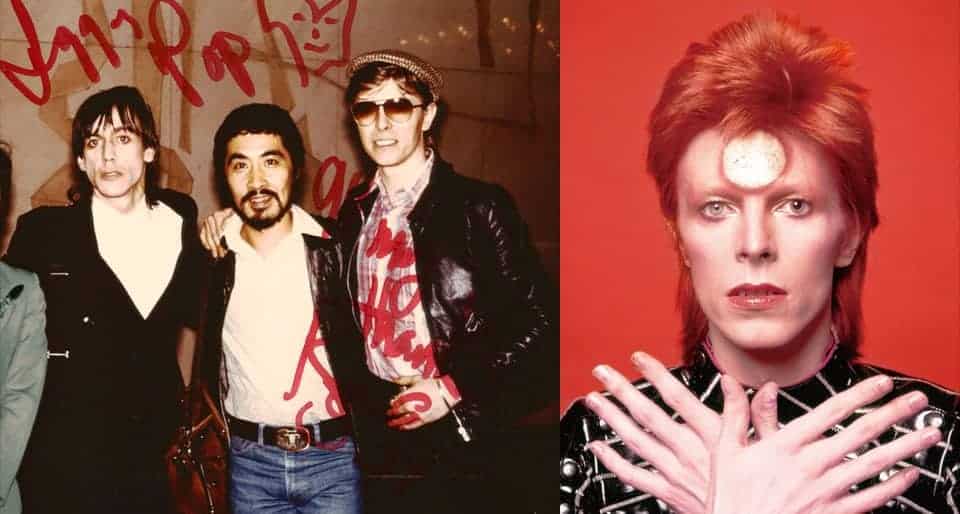

At the same time, and as a number of them include music (music from the time period of the lost silents – earliest is 1906 by Maria Carpena, from the vast personal archive of Nestor Vera Cruz – his Yesteryear gallery had the biggest collection of Philippine music vinyl) that occasionally features American or Spanish connotations, the colonialist past of the country is also showcased, adding even more depth to a narrative that is as rich as it is abstract. Lastly, the fact that the film speed is much higher than usual works quite well for the entertainment it offers, occasionally giving a comedic essence to the otherwise horrific images presented on screen.

Essentially what Khavn achieves here is to make the archiving of films into art, in a title that is, as usually, not directed to the “average” viewer, but still has a lot to explore for both the buff and the fan of experimental cinema.