Bina Paul graduated from the Indian Film and Television Institute with a major in editing. She edited more than 50 feature films and worked with illustrious directors such as G. Aravindan, John Abraham and P. N. Menon. She received two national awards and numerous state awards for editing. She was the artistic director of the Kerala International Film Festival and the Kerala International Documentary and Short Film Festival. It contributes to making these two festivals important international events. She is part of the juries of several international film festivals, notably in Locarno, Durban, Morocco and Berlin. She is currently co-chair of NETPAC. She also directs and produces documentaries. His latest film, The Sound of Silence, screened at numerous national and international festivals.

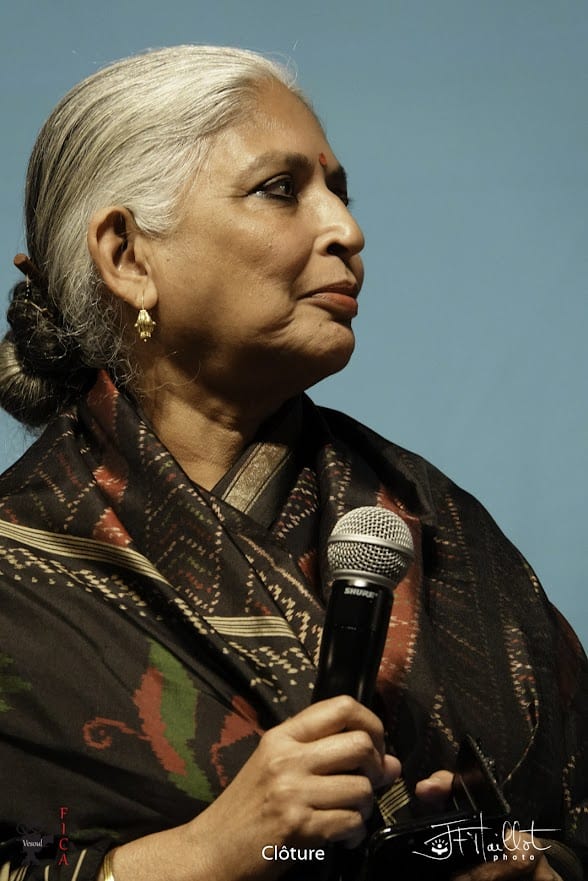

On the occasion of her presence as the head of the NETPAC jury at FICA Vesoul, we speak with her about her career, Kerala Film Festival, the Malayalam movie industry, editing, film societies, NETPAC and many other topics.

You have been in the industry for decades now. What do you feel are the biggest changes you have seen in cinema and then to yourself as an artist?

As far as the cinema is concerned, I started working on 84 / 85, around that time. Of course, technology has changed, all that is pretty obvious stuff, in terms of what's happened to the actual process of filmmaking. But talking from the point of view of Asian cinema, at that time, literally, nobody knew about Asian cinema. There was this magazine that we used to read called Cinemaya, which was literally one's first introduction to the fact that there is something, or there is something to acknowledge, like Asian cinema. It's only a little later that it became more fashionable. But in those days, to even want to see an Asian film was impossible. To hear about filmmakers, to understand the history of the Asian nations, in terms of cinema was very, very difficult. And I remember the same people who ran Cinemaya (who later also set up NETPAC i.e. Aruna Vasudev), they ran a festival called Osian's Asian Film Festival. You were reading about these films through Cinemaya and then you got to see these films. And I remember seeing a lot of films from Korea, a lot of films from the Philippines. It was mind-blowing, and you just didn't even know they existed because I had gone to film school and in film school, other than of course, Kurosawa, Ozu or the big masters, there was just no understanding of Asian cinema at all. We were sort of bred and fed on European or American cinema and, of course, Indian cinema a little bit. So I think that is the biggest change, that Asian cinema has sort of become center stage quite a bit now. That is the biggest change I've seen.

For myself, I would say that I've grown of course as an artist, I've grown as a person with programming. And more and more sort of attracted to the “Glocal”. If it is to coin a word, which is global but local. I think that the problem with film is this great availability of films, for example, now you get Netflix, and you can see anything. But the importance of the festival is curation. I don't know what film to watch on Netflix frankly. I don't even know half the films exist, or on Mubi a little more maybe. So I think film festivals are really important. Still for the fact that you know that somebody has watched these films, somebody has chosen these films, and somebody's wanting to show you these films. I think there has been an important sort of understanding of the need, the crucial need for preserving these film festival spaces. Because at one point, everybody said: “Oh, it's all available. It's all available on the internet. Why do you want to go to a film festival? You don't need to go to a film festival.” But now, you know, it's not the internet. It is the business of watching together, of discussing, of seeing, of having somebody show you history, you know. For me, that's the most important.

Your main occupation is editor. There's always a misconception about that. Where does the editor stop and the director begins?

The director never stops. I think I've always been conscious. I've worked with some of the biggest masters in Indian cinema. And your art or your tools are to further the vision of the director. I have never had any doubt about it. It's not my film, it's the director's film. But yes, your intervention and your artistic intervention has to be done very silently. I must say that the problem with editing is it has to be very self-effacing. You cannot see good editing. You must not see good editing. Editing is something that if you say “oh a film was well edited”, you're actually saying “the film is very flashily edited”. I think editing is that which translates your tools perfectly for the film. What the film needs, and not what you think you do or what you are. So yeah, for me, there's no question that the director is the captain.

Maybe that's why you have worked with so many directors?

No, because actually I'm a very argumentative editor. But I know that this argument is for the film. I think directors who work with me understand it is for the film. So yeah, I'm not an editor who'll say “OK, do it any old way.”

From the experience you've had with all those major filmmakers, is there anyone or a couple who stand out for you?

Well, I think the starting point of one of the early films I did was a very important cult film, which you can find on the internet now, called “Amma Ariyan” by John Abraham. Two or three things about that film. One is, of course, it's 35 years old now, but it's one of the most revered films in India. Secondly, the process of making, actually we formed a collective, we collected money. We made the film through that process, which was also really important for me, that it was truly a kind of people's cinema. Thirdly, it was never released. It never had an official release. But it has had over 6000 screenings. It was carried by this collective from village to village, from town to town and screened. And then of course, it had a lot of international exposure. Yeah, so that was a very important experience for me, because the filmmaker was a fantastic person. He has passed away, he was a total anarchist, but he was a good friend. And he passed away soon after the film was made. Unfortunately, he had an accident.

But I learned a lot. It was a very early film for me. That's where I learned that the most important question is, “how do you translate the vision of a director?” Because I was so argumentative at that age. I was very young and I kept saying “no, this is the way to do it. No, this is the way.” And he would fight with me and say “no, this is what I want. This is what I'm looking for. This is what I'm doing.” And now when many years later, I see the film, I understand that he had the bigger picture. I had only a smaller picture. There are so many things you learn, everything is new in a film. Every time I sit down to edit a film, I get so nervous. It's like your first film, because each time there are so many challenges. So it's not one person who teaches you, it's lots of people.

You have edited films of your husband?

Yes, all his films so far.

Does it make it even more difficult that you're arguing with him?

It does, it does actually. I must say that, being so close, it's also a disadvantage because I think I perhaps overstep. Because you know, you feel a certain ownership. And then this division of the director and editor doesn't exist a little bit and that is a bit problematic. But I think I've done my best editing with him. Some of the films that he has made, the first one which he got the National Award, and I got many awards. When I look at that film today, I think it's so well edited.

Which one is that?

It's called Daya. “Daya” means sympathy. It's a fantasy tale and it's written by a very well-known writer in Kerala. Recently, when I was going through some papers, I found a letter from this very great lady who was a film editor who was a little older than me, she has also passed away unfortunately. But she saw the film, and she wrote me a letter about the editing. And it's such a warm letter, and she just understood completely that it's a well-edited film. That was nice. Her name was Renu Saluja.

You smile when you speak about this…

Yes because, you know, often you don't look at your own work very objectively, and you're always worried and you're always thinking “is it okay?” But yeah, this one I like.

Can you tell me a bit about the Kerala Film Festival? You were one of the people who started it?

Yes, one of the early ones. The Kerala Film Festival. Actually, if you know the history of Kerala, it's a very literate state and it's the only elected communist government in India. It had a very strong history of film societies. Out of this whole literacy movement and culture for the people etc, there was a long history of strong film societies. So every town had a film society everywhere that were showing films etc. And, in the 80s, with the coming of DVDs and this and that and all that, the film society movement was sort of waning. Some of us were quite worried about that and said “now people are not watching films, there's no international culture coming, it's all about Malayalam cinema etc”.

When was that?

Maybe 88, maybe around that time. So actually, a very informed bureaucrat, and the head of the Indian archives, was from Kerala. So he and his bureaucrats said: “Let's do a festival, which only consists of films from the archives. Let's show it in the theater, let people come back to the theater.” And that was a very successful edition, people just suddenly rediscovered the classics coming back. So that's when I also got involved. And we thought, let's make a small festival and see. We showed a few films. It was, you know, the day when you were carrying 35 mm from France, 35 mm films were coming and from Italy, a 35 mm print was coming. It was really a nightmare! In the first instance, I think we had only two theaters and I was so worried. Will there be an audience or 300? And slowly we built on that.

Now we show in 14 screens, we show about 200 films and we have about 15,000 people who attend the festival. We count the delegate registrations, the cinema footfall may be very much higher. So it is one of the most important cultural events in Kerala today. Now governments may change, everything may change but the Kerala Film Fest remains. What it has done is, it has affected the local filmmaking culture. Today, Malayalam cinema is one of the strongest in India. I personally believe that one of the reasons is the festival, because most of the young filmmakers have come to the festival, have watched films, have been exposed to directors. I think that has now started showing in the filmmaking. So the Kerala Film Festival is a very very important cultural phenomenon.

You're no longer with them are you?

Well, no, I retired last year.

Was that your decision or …?

You know how politics are. I was thinking “enough” but I was also told so. So it was a combination. It was a natural change because the government changed etc. But they could have done it a little better, maybe differently? But …

You don't have any grudges?

No, no, no grudges, no grudges at all. I think the festival needed that change, it's time that there was a new artistic director. My vision brought it here. That needs to be changed. So that was not at all the problem. The problem was that you do feel sometimes that, you know, will history acknowledge what you did etc etc? How do you write history? We'll have to see how long it takes.

How would you describe the situation of the Malayalam movie industry at the moment?

Oh, the Malayalam industry is very interesting now. As I said, so many filmmakers have come through the festival. You ask them: “Where did you learn filmmaking?” “At the Kerala Film Festival”, they say. So there are many young filmmakers. Of course, there are the strong commercial movies that continue. Of course, you have the stars and all that. But alongside that, there is … we can't call it independent filmmaking but it is a kind of strong independent filmmaking that is being seen not only in the theaters, but on the platforms, and being recognized all across India in spite of it being regional. And they are pushing narratives, they're pushing all sorts of things. I mean, it's really an exploding industry at the moment, very interesting. And I think everybody in India and the world is acknowledging that Malayalam cinema is one of the most interesting in India today.

There is a star system, I guess, in almost every industry. How important do you think that is?

The thing is that we have a few stars, and they're doing pretty well. But we're also seeing films without stars doing pretty well. So the star system, of course, continues strongly, but not overridingly so. Unlike in Bollywood, where the star system is very strong. In Kerala, it's not overriding the whole industry. People dare to make films without stars, people dare to release their films without stars. People dare to experiment with cinema's language. And in fact, in a very alternative kind of film, a big star has just acted. So that crossover has also taken place, that they are looking at this kind of cinema as well.

Regarding censorship, what is the situation now?

That's the same as everywhere else in India. We have a sense of “oh you have to get passed and you have to have so much dialogue”. But filmmakers find ways I think. I see a lot of stories being told and I think that filmmakers are finding ways.

Despite the fact that India is the biggest industry in terms of number of movies in the whole world, it has not been recognized outside the country except maybe Bollywood and some of the most famous filmmakers, like Satyajit Ray. Why do you think that is?

I think it's because we have such a strong audience in India and you don't need it. I mean in Kerala, if a film is made, we cannot hold it until Cannes or wait for it to premiere here and premiere there. They just release it at once and there's an audience to see it. So why will you hold your films? I think one of the main reasons is that the audience within the country is very strong. Of course critical acclaim is important. Some filmmakers believe that they should hold on but it's getting better I think. You're getting to see more films now.

But again it's the same story. Now Europe is no longer interested. I see a lot of the international film festivals are not interested in Asian films. There is a kind of star hierarchy within the big festivals which is recurring. In between it was quite popular to have good Asian cinema, Hindi cinema etc. Now it's run by sales agents a lot.

So it's not exactly your position to say, but would you say that if festivals outside of India would like to screen Indian movies, is it easy cooperating with the people for the rights in India?

No, it's not so difficult. But the business of the premiere show is difficult. If you want to have a premiere of an Indian film, it's difficult. Unless your film is made, and it's within the next month or two of the festival, then you might get a premiere show. But otherwise, they want to show it in India first, mostly. But negotiating with India is not difficult. I mean, in the past, it used to be but now it isn't.

In your work as editor, have you ever had actors intervening?

No. Director, yes, of course. I don't even like the cinematographer because the cinematographer is the most interfering person actually. They go: “why is the shot there, why is the shot not used etc”. But I also have to say I've not worked in the star system. I've not worked there, so maybe they do. But I've always worked in the slightly more indie and sort of the arthouse space or let's say middle cinema space. I mean, I've edited films of big stars but they're not expecting to be the big stars. Or maybe they do it, I don't know. No, I don't know. Maybe the director knows how to do it – when you cast somebody you know that you have to promote that person.

And if you were to mention some names from the Kerala movie industry at the moment?

There is a young boy called Lijo Jose Pellissery, there is Mahesh Narayanan whose film was just shown in Locarno. There is Anjali Menon. There are few women unfortunately, but not enough. So there is our actor Fahadh Fazil, who's done very well. There are quite a few filmmakers who are rather young. There are lots of youngsters, but Lijo and Mahesh have sort of leaped I think.

Being a woman in this industry, when you started was it easy or difficult?

Difficult, difficult, difficult, even today.

Even today because you have to tell men what to do occasionally?

No. I've sort of reached a point in my career that I don't think anybody will tell me what to do. But they don't like it because they probably think they don't want me to tell them what to do. Being a woman is very very difficult. And in fact, a few years ago, three years ago in Kerala, we formed a collective of women, which is called the Women in Cinema Collective (WCC). It was a very important moment because we all came together and said that it's time we created a space. You know, when you go to a film set in Kerala, there'll be 80 men and maybe one or two women. So automatically, it becomes a heavy minority. These are the issues we're trying to address: that women have to be given more space, more opportunity, more scholarships to study cinema. So yeah it was a tough time for me in the beginning. I was very lucky. I worked with very, very important good directors and I got a lot of respect. But I see that for a lot of girls, it's very overpowering, not sort of being taken seriously just because you're a woman.

Can you tell me a bit about the impact of film societies? I don't think there is anywhere else in the world where film societies have such an impact as in India.

The film society movement in India is still strong. Actually in Kerala, it has revived. It is one of the strongest. You know that Satyajit Ray set up the first film society in India? The very first, and that has sort of permeated all over and still continues. But I do think that in Morocco, in Carthage and all these places … Tunisia, they have film societies as well. I think a lot of these places where there are good film festivals start with good film societies. Like film clubs. In Greece, you don't have film societies, film clubs no?

There are some clubs, but they are not impactful at all.

Yeah? Oh they're very impactful in India. At least in Kerala, definitely from the 60s till the 80s. They were very strong, then the Kerala Film Festival came. And again, there's been an interest now. And there's a revival because now it's easier also to show with all these links and piracy.

Piracy is a proper part of the conversation now isn't it?

Oh, totally. You know, the dilemma is, the film is available. Should more people see it or should we protect the artist? Sometimes I think it's better for people to see it. That's the story. I mean, it is a dilemma. Because when it's your own film … I mean, I know that some films I've edited, on the second day, it's available online and you're thinking: “oh, no, it's going to affect business”. But on the other hand, five years down the line, at least you can see this film. I mean, this film, I'm talking about “Amma Ariyan”, which is really such an important film. That is now available on YouTube. Luckily, otherwise who would see it?

Do you plan to continue working? Are you tired?

No no I'm not tired. It's just that I need to, I think perhaps reassess. I'd like to edit much more. Editing sort of took a bit of a backburner over the last 3 to 4 years. Yeah so I've gone back to editing a bit more. And I am really interested in this promotion of Indian cinema. So I'm working with some festivals. And of course, NETPAC, where I'm trying to promote Asian cinema on the whole, or at least create this network of people who know each other, who exchange views. That is, I think, for me the most important.

Can you tell me a bit about NETPAC, what do you think of its status now?

So NETPAC was set up, as I told you, 25 or 30 years ago with this idea of promotion. At that time, of course, it was so crucial. For the Busan Film Festival, with Kim Dong-ho and all these guys, NETPAC was a very important part of that moment, when they said Busan has a film festival. At that time it was called Pusan Film Festival. And regarding NETPAC, there were all those moments in history where they said, you know, Asian cinema needs you. Now when you look 25-30 years down the line, you don't need anybody to tell you about Asian cinema, a lot of people know where the films are. But what I think is still missing is a bit of scholarship. And that is what I think NETPAC needs to do now. That we need to create networks of scholarship, people should study, should understand, should share. And I think that is more the effort. Now we don't need to promote individual films or filmmakers. But I'm very interested in what's happening now in the Philippines and in the restoration space, that kind of thing. Can we get and show a package of those films around? Can we have conversations around it, discussions etc? So I think that is the future. Unfortunately, NETPAC is not as vibrant as it used to be. We're trying to work and revive in a different direction a little bit.