As the discourse in Japan regarding same-sex marriage is currently on the rise, films about the topic overall are bound to come out in more frequency. One of those films is Daishi Matsunaga's “Egoist”, based on the homonymous, autobiographical novel by Makoto Takayama, which was recently screened in Tokyo International.

“Egoist” is screening at Udine Far East Film Festival

When Kosuke was 14 years old, his mother died. He spent his adolescence in a rural village and suppressed his feelings as a gay male. As the film begins, however, we find him having turned his life completely upside down, working as a fashion magazine editor in Tokyo, looking rather smart in his designer clothes and overall handsomeness, and having a circle of friends that seem both dedicated and a constant source of fun for him. One day, after the suggestion of one of them, Kosuke starts working with Ryuta, a young personal trainer whose mother has raised him alone essentially. The two connect on a number of levels and soon start a relationship, but the financial disparity between them remains an issue. Kosuke, though, is willing to ignore the fact, even starting giving the trainer money at frequent intervals, which he uses to also support his mom. Their relationship becomes better and better, and Kosuke also starts getting along with Ryuta's mother, but tragedy soon knocks the door.

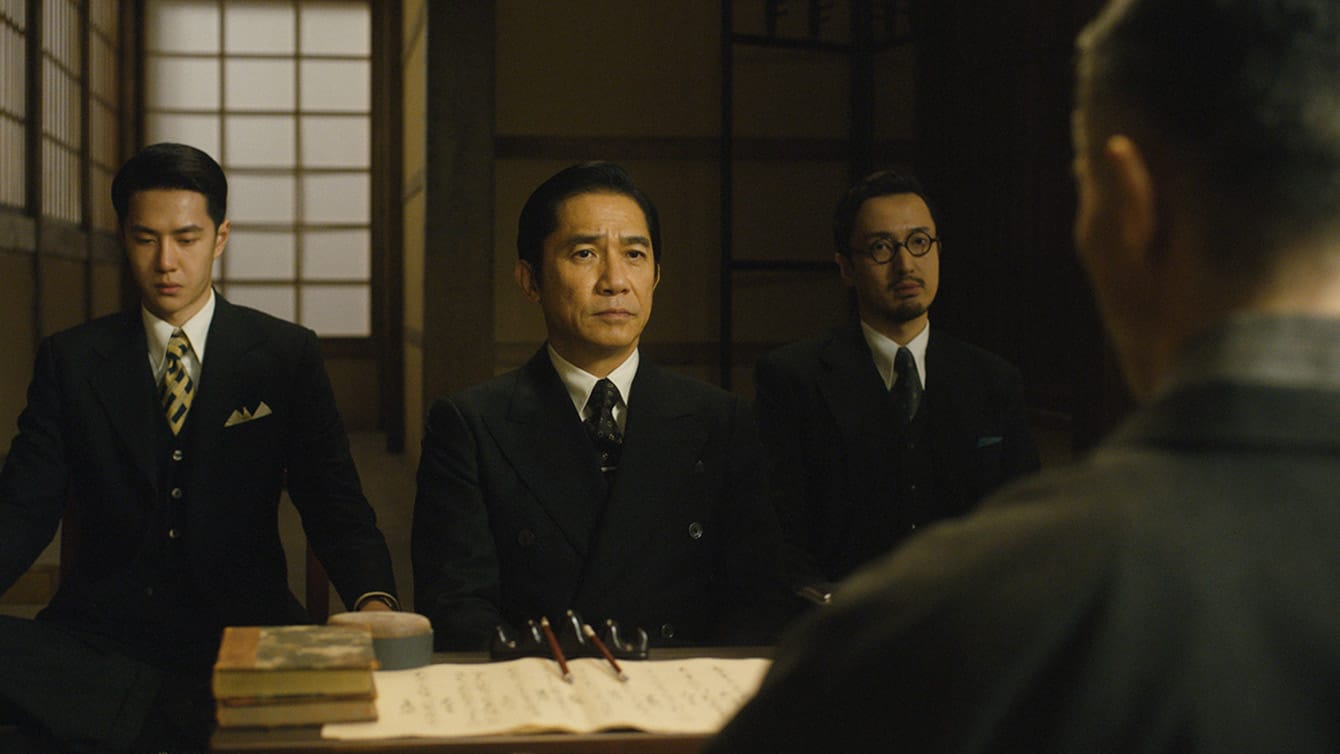

Implementing a realism in art-house fashion that allows the movie to unfold as a biopic of sorts, Matsunaga comes up with a movie that showcases the lives of homosexuals in Japan quite accurately, and with a sense of sensitivity. The frequent sex scenes that take place in the first part is definitely one medium of this approach, which soon actually extends to include the phenomenon of disparity and how it can affect relationships nowadays. In that way, what Matsunaga accomplishes here is to create a movie that goes beyond its LGBT premises, instead presenting a romantic drama in the usual Japanese style, where the protagonists happen to be homosexuals. This approach is quite unique, particularly because it presents the concept as something normal, a common part of society, thus avoiding any kind of exotification or “racism porn” that is usually the approach of the movies with that particular theme.

Also of note here is the portrait of Kosuke, which is quite thorough in its presentation, with Matsunaga analyzing his protagonist both in conjunction to his past, but also through his interactions with his friends, Ryuta, and his mother, even occasionally with himself, as the scenes in front of the mirror showcase. This approach allows the audience to empathize with him, while retaining interest for the majority of the movie, although the regular lagging in the end is not missing from here either. This aspect also gains a lot from the excellent performance of Ryohei Suzuki, who presents the various layers of Kosuke, from his cockiness and self-indulgence to his kindness and politeness with equal artistry, in one of the best traits of the movie.

Hio Miyazawa as Ryuta is also convincing, but his character is somewhat underdeveloped, resulting in the most significant fault of the movie, as the nature of their relationship, particularly the fact that Kosuke essentially finances Ryuta, could have been explored a bit more thoroughly. On the other hand, the concept of grief and loss, and how family bonds are created even among people who do not share the same blood is excellently portrayed, dominating the last part in a very rewarding fashion.

Naoya Ikeda's cinematography implements a number of close-shots that occasionally give the movie a documentary feeling, while the grayish tones that dominate the images fit the narrative nicely. Ryo Hayano's editing results in a relatively slow pace, although the cuts to the restaurant gatherings and the montage with music that takes place add a very welcome sense of speed to the movie.

Despite a few faults here and there, “Egoist” emerges as an excellent drama, particularly due to the approach Matsunaga implemented to present his main theme.