Talal Derki was born in Damascus, Syria in 1977, studied film directing in Athens and has lived in Berlin since 2013. His short films and documentaries have won numerous awards at festivals, with Return to Homs and Of Fathers and Sons both winning the Grand Jury Prize at the Sundance Film Festival. Of Fathers and Sons was also nominated for an Oscar and won Lolas at the 2019 German Film Awards for Best Documentary and Best Editing.

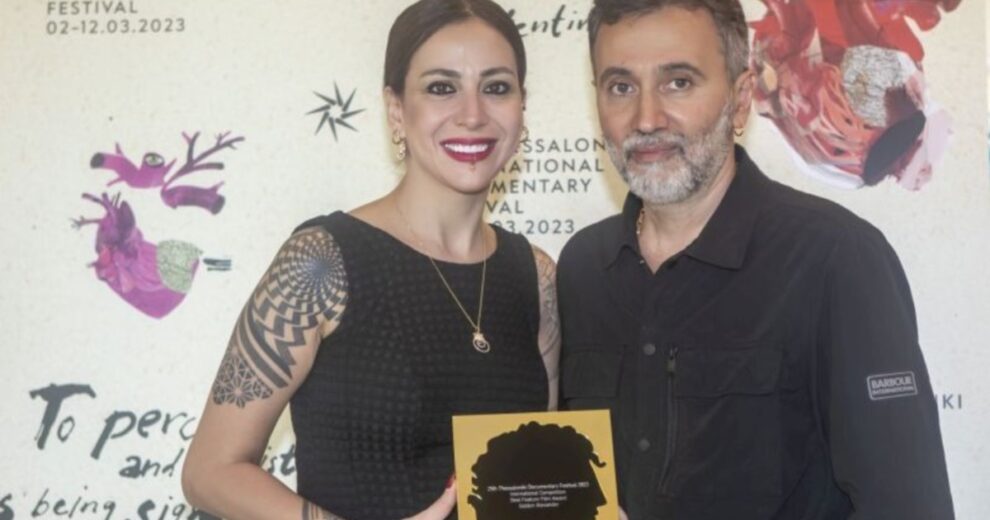

On the occasion of his latest film, “Under the Sky of Damascus”, screening in Thessaloniki Documentary Film Festival, where it won the Golden Alexander, we speak with him about the story and the motivation behind the movie, patriarchy and the place of women in Syria, the incident with the line producer, the current situation in the country, and other topics.

The first question that must have come to everyone's mind, is how this whole thing came to be? The whole story from the beginning until it was made into a movie. Can you walk us through the path?

It was a long process. When me and Heba Khaled were observing the situation in Damascus, regarding the third part of the trilogy and what the story is supposed to be, we realized that the most important question during the last 10 years, which was not mentioned at all it in my films and any film that came out of Syria, was, “Where is the woman?” We decided to focus on this question, not only because people kept asking it, but also because it is the root of most problems, the fact that Syrian society is so patriarchal and that, still, toxic masculinity covers the whole world. Men are selfish, taking decisions and acting in the last 10 years, without sharing or asking the opinions of others, as, for example, of the women in society. It is scary. We were also instigated by all the crimes we used to hear on websites, on social media: every week, there is a new woman or girl killed under the title of “honor killing”. This is the post war situation. We also tried to focus on the history and culture of Syria outside the usual storytelling about refugees, soldiers, and victims, etc. We tried to present a story that could unite all sides, because it happened everywhere, not only in Syria. Even in Europe, it is happening on different levels. When we met the characters, we knew that this could happen.

But how did the practical aspect of the shooting work? You were in Berlin, others were in Damascus, how did that work?

In the beginning it was difficult to find a person whom we can trust, because we are blacklisted somehow, we live in exile, we cannot go to Syria. We had to observe, to control, to be sure that our vision would be reflected correctly in the shooting. That they are people who really believe in what we are doing and we can trust them. It was difficult until we found Ali Wajeeh, who is a famous script writer and film critic. And discussion after discussion after discussion, we talked for more than six months regarding the preparations. In the end, we managed to bring the best DOP, find the characters, the best researcher Zeina Shahla. who is a woman rights activist and a journalist. So, the scriptwriter, the human activist and the DOP started building the whole thing and then we found the company when they found Adel, the guy who becomes known as Tory in the film. We were really in contact about every single detail since the start of the shooting. We had a camera, we had live shooting, and also a video call, with the camera directly stacked to the monitor with the tripod and the headphones, which were connected, won with the director and one with the DOP. We really tried as much as possible to create this collaboration between us and the team on the ground.

It is difficult to film remotely, but we did not have any other choice, it is our homeland. Damascus is the capital of Syria and more than 6 million live there today, 90% of them under the line of poverty. There is no middle class anymore. This is where we end the trilogy after “Return to Homs” and “Of Fathers and Sons”

Check the review of the film

But there was no kind of dramatization in the movie, right?

There is no kind of dramatization. We researched a lot of characters, until we found real people who believed in our purpose. People who were really radical about women's rights and the way that men should deal with them in Syria. We found those people, we agreed about all these issues, and we tried to follow their stories. Some of them had strong family stories, some of them have their families outside of Damascus, so we could not bring in their stories. The women who are speaking, their testimonies came 100% from them, we did not interfere. The only thing we did is select stories that can really open the door for more questions, because some stories were very similar. We really had a lot of interviews.

In the end, it was not our choice that the play ended up in this way, it's not our choice that we stopped the shooting because the line producer betrayed us, it's something that happened, and you have to deal with it or, or you have to lose it. That's what's the big challenge when we have those crises, how to protect the characters, how to win against those people who do those acts. So there are many issues we had to consider in our mind. In the shooting, there was no interference by us. Only during the editing, we selected what is going to be included in the movie, as any director would do. We selected the scenes that can build the dramaturgy and united the different scenes together in order to create the structure of the film?

Since you mentioned the line producer, how shocking was what happened? Considering the nature of the movie, having a man actually doing this in this movie must have been really shocking, right?

It's absurd. But it also proved the point of our film. After we managed to get out of this chaotic situation, after we fixed the problem, we started to observe what happened and tried to include it in the film because we believed that the film itself was the only way this power could be defeated, the only way something could change. This is why we are shooting films, non-fiction films. It was shocking for us and even more for the people on the ground like the director and the DOP. They were really shocked because they were in contact every day and that he would behave in that way. What happened proved that the sexual exploitation of women is one of the main illnesses of society, one of the reasons society is suffering. Before the war, and even more now, after the war.

Regarding the interviews of women that were in the film, was it difficult gaining their trust to speak on camera?

That surprised us, because in the past, it was difficult to bring in any woman and speak about these topics, because society and families always blame the woman, if she speaks out. But now, it has become the opposite. Those who did not want to show their faces, we shot them from a distance. Those who were able to face the camera and make this decision, we shot normal interviews with them. There were a few in the end, but most women did not want to reveal their identity. This is why we have these theater actresses because they are free, open minded, they have the courage, the way to convince, to explain, to make people more courageous about speaking out. That was the deal, that we are supporting the play and they are supporting us. What we found is that the society is almost ready to to scream, the women in Syria are already screaming and they are fed up and they are ready to tell and to move the shame from them to those who did crimes against them. And it's good that the film is out, for people all around the world to tell them that they are not alone, that they stand with them.

So you think cinema can make real change?

It can play a role, it can open eyes. The real change comes from action, but cinema can really raise questions that build motivation, that give real understanding about certain situations. Until now, people in Syria told us that they believed it is not the time for this film. The political war, the actual war are the most urgent topics for them and they want to keep talking about it. In that fashion, it will never be the time for women stories or human tragedies, that is why, as I said before, we are trying to build an understanding about one of the biggest war, what we call “The Forgotten War”. It's the war that happens in every house in Syria, and it is due to the violence involved that we deem it a war. It is a war nobody in Syria wants to talk about

One of the actress's family also features in the film. Were they open to being filmed?

I think they were open. This family is not a regular sample of families in Syria, the way the father behaves for example. We tried to have a balance, to present a good father compared to the stories you hear in the film about fathers hitting and torturing etc, one who truly supports his daughter, even when she is leaving the house. We feel this is a very significant issue, because the society itself is divided even within families. There are people who believe different things and then they really split, they stop talking to each other. Me also, there are family members whom I stopped talking to because they were pro-dictatorship or stay silent or support the massacres that have happened.

How did the shooting inside those institutions work? There is a center for deaf and mute women and a mental hospital but how did you manage to shoot inside them?. Did you ask for permission?

We had permission. We did it in this way because if you shoot secretly, undercover then you would put the people that work with you in danger. Maybe after you shoot for two or three minutes, somebody from the secret service will catch and ask you “what you are doing, show me the material, come with me”. So we didn't want to put the people in danger and that's why one of the biggest strategies we had is we tried to find people who would not have to deal with problems from the government afterwards, when the film is released.

Syria is very famous for its drama series, so we applied as if we were doing a fiction drama and we sent the synopsis to the Artist Guild, where most of the dramas get permission to shoot, we got the permission on paper and with this we managed to shoot in the places you mentioned. Some places were rejected, some were open. When we went to the mental hospital, we talked to the head doctor, we talked to the nurses, and we selected only those patients who have psychological problems, but not a mental problem. For example, we talked to people with depression, who could communicate, not those with more serious mental problems.

There were also those who did not want to appear on camera so we had to blur their faces, and there were also cases after the shooting, when someone would say that they did not want to be in the film. For example, we had another block with people who are extras in movies, and they talked about how the producers exploit them. After a month of the shooting, and by that time, we had already selected the scenes for the final version of the movie, we received a call and they told us that they do not want to appear in the film. Therefore, we had to take the whole block out. That was a block with one of the main characters, so in the end, we could not have her research in the film. We really tried to make sure no one was in danger. Of course, those who were included, those who really want to face the toxic masculinity in society they may have problems later on, but that is the challenge, the war we are opening. And we are ready to fight.

How much time did you take shooting and how much editing?

In March 2020, we started researching and we started shooting in the summer of the same year and we ended the shooting at the end of 2021. But then we had to do some extra shooting. So, around a year and a half of shooting. And the same with editing, selecting material. This is the most time I have spent editing a film. It wasn't easy at all, because we had different characters, not only one. There were many characters and there were twists, and to bring all that to 90 minutes was not easy at all.

How did the girls feel the first time that they saw the movie on the big screen?

They really supported us, they were with us in Berlinale and in CPH:DOX. They talked, they explained, they told stories. They admitted that what you see in the film is less than a quarter of what is happening in reality, which is much more heartbreaking

Outside of the topic of the film, can you give me some details about what is happening now in Syria, how is the situation there?

I am not an expert to talk about Syria, because I don't live there anymore. However, my family is there and I hear stories from them about the economic situation. As I said, 90% of people are under the line of poverty, the middle class has collapsed, it does not exist anymore. People struggle to meet their daily needs, food for example. The country is closed, it is difficult to travel abroad. Everything is expensive. The Syrian regime won the war and is controlling the whole region. There is no political freedom, economically it is the worst place on the planet. People still struggle to protect their dignity. Some people left, and those who left, do not want to hear about those who were left behind.

When was the last time you were in Syria?

I was in the north of Syria shooting “Of Fathers and Sons”. That was until 2016. But I fled from Damascus in 2012, eleven years ago.

Will you be arrested if you go back?

Of course. If you are not getting arrested at the border, when you enter the country, then in the way, you will disappear somehow. I don't want to say that this is 100% of the situation now, but I still don't want to risk my life for this.

What are you working on next?

I'm producing a film. We shot it in Afghanistan, it will be released at the end of the summer, in film festivals. Also, I'm planning to start my new documentary as a director. So that also can start in the summer. I'm doing the research now. I am also joining Heba Khaled in various festivals at the moment, so that is the plan for the rest of the year.

I consider documentary filmmakers the heroes of the industry. Because it takes too much time to shoot a documentary, and then it is very difficult to break even. So, my question is it, does it make sense financially, can one actually support themselves by shooting documentaries?

It is difficult to explain about this. It is difficult to make a living by making documentaries. It takes time until you can find the balance, to gain enough money to fit your way of living. In general, living in Europe and in capitalist countries, it is difficult to make a living as a freelance artist, not only as a documentary filmmaker. I hope this film can sell because, Heba, for example, did not get her fee because we tried to push every fund we had into the shooting and into making this film. We have some gap in the budget, even if I am Oscar-nominated etc. It was a difficult topic, because now people are more interested in what is happening in the Ukraine for example. But in the end, we survive to complete it.