Various themes run throughout the work of Hirokazu Koreeda. Without doubt an auteur, there are two key themes that feature regularly in his work: a breaking away from the conventional family unit; and memory, specifically holding on to the past. Within the former, fathers are often portrayed as weak individuals, some worthy of sympathy, some not. Often, they are absent cowards, enigmas and/or bitter men, but all have a difficulty facing up to the responsibility of fatherhood.

Most of his films pose the question of ‘what makes a good father?' though often this could be interpreted as ‘is it possible to be a good father?' with many seemingly not up to the task. Here are five examples of the difficult questions Koreeda poses of fatherhood – where fathers are failing the expectations of their role – and where he offers them no easy answers.

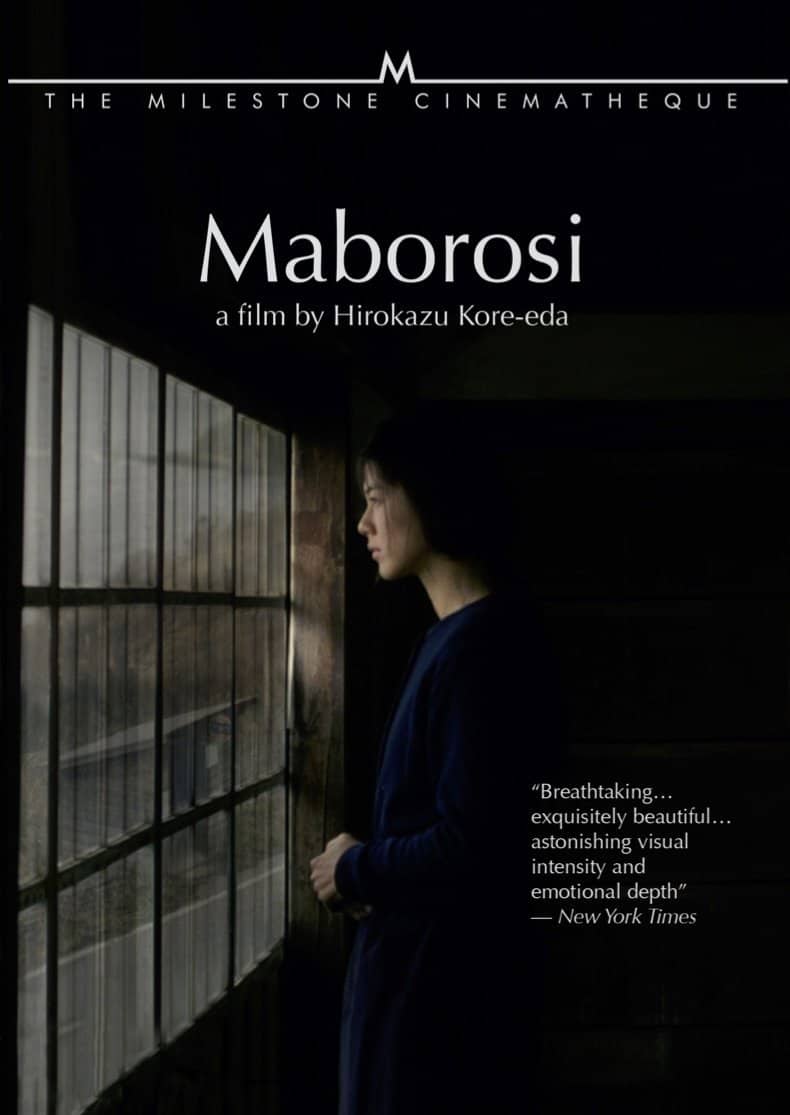

1. Maborosi (1995)

Following the inexplicable suicide of her husband Ikuo (Tadanobu Asano), Yumiko (Makiko Esumi) struggles to come to terms with the loss, and so lives her life as a ghost in the twilight. Remarrying, where her first husband has selfishly shirked his responsibility of raising their new-born son, her new husband Tamio (Takashi Naito) is a widower who is selfless in all that he does. Dedicated to his daughter, he works hard to provide for his family, and is the perfect father figure for Yumiko's son, Yuichi.

With Yuichi now having two fathers, three key sequences beautifully exemplify Koreeda's nature versus nurture debate that preoccupies his work. The musical introduction shows Ikuo riding a bike he has stolen. Having had his own bike stolen, he travels to an upmarket neighbourhood to pass on his misfortune. In his seemingly idyllic life with Yumiko, the pair happily paint the bike green.

Having moved to her new home in a small village, Yumiko discusses her previous marriage with one of the village elders. She is told Yuichi not having known his father is perhaps a blessing as he'll know no different. But as Yumiko looks out for her son, she sees him by a bike shop, looking at a green bike. His ringing of the bell sounds like daggers to Yumiko, as she sees her son will never know his father, but he will always be part of him.

The film's coda shows Yumiko sit on the porch with her enigmatic new father-in-law as some sun finally enters her life. They look down on Tamio as he teaches Yuichi to ride the same green bike he had favoured at the shop. It is a happy scene, that shows both nature and nurture will form Yuichi as he grows; Tamio having taken the baton from Ikuo in raising him, suggesting he will have a happier future with his stepfather.

2. Without Memory (1996)

“Without Memory” is a real-life scenario of the situation many of his fictional characters find themselves in: notably between two worlds. Suffering from Wernicke's Kosakoff Syndrome after medical negligence, Hiroshi Sekine, the subject of the documentary, is a man forgotten by Japanese bureaucracy, having to live the rest of his life unable to form new memories.

A husband and father to two sons, they quite literally grow in the blink of an eye from his perspective. Each day they are another day older, yet to him they will always be the age they were when he had his fateful operation. He will be unable to see how they develop and grow naturally, significantly impacting on his ability to have a role in the upbringing of two boys who increasingly become strangers. The problem is furthered when his wife announces she is pregnant with his daughter: a girl he will have no knowledge of each and every morning.

“Nobody Knows” explores the world of forgotten children, though here the father simply struggles to remember his children. Hiroshi is not an intentionally bad father, though he will always be a father figure his children will struggle with, not able to fulfil his role in a way they want and need. Unable to share in his children's lives, they will forever have and not have a father.

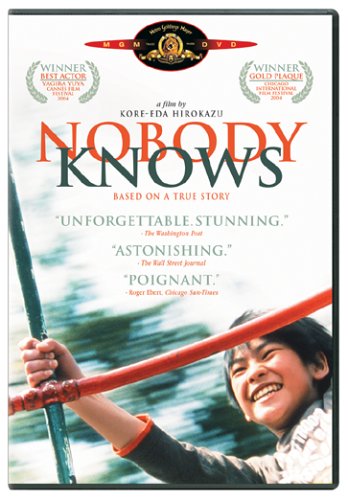

3. Nobody Knows (2004)

Based on the real-life case of “The West Sugamo 4 Abandoned Children Incident” from the 1980s, this is Kore-eda's magnum opus, in that he took fifteen years to conceive and finally make the film. But a story of four children abandoned by their mother with tragic consequences is not simply a tale of a bad mother, but a bad society in general. A single mother with four children all fathered by different men shows her as a selfish woman who repeatedly makes bad choices, but also reminds us that each of these children had first been abandoned by their fathers.

Each child only knows of their fathers what their mother, Keiko (YOU), tells them; and how much of that is actually true is to be taken with a pinch of salt. She talks with great pride at how her eldest, Akira (Cannes-winning Yuya Yagira), is the son of an airport worker, though in a comedic couple of exchanges, we learn more as to the nature of Keiko's lovers.

Akira pesters two former boyfriends for money, on the possible truth that they are youngest Yuki's (Momoko Shimizu) father. One works as a taxi driver, also appearing to sleep in his taxi; while the other works at a pachinko parlour. Both talk with Akira in a friendly manner, having known him while dating his mother, but both deny they have any money to give him, beyond pocket change, though also both end the exchanges denying Yuki is theirs.

Both show a lack of caring for their potential child, and indeed, four lost children in a bind. They are examples of a society that has become selfish, individual and without care for others. As there is no proof that either is her father, both choose to believe they are not. As such, they can simply ignore the situation as not their problem, despite being no doubt directly responsible for it. Society as a father has also abandoned these children.

As the fathers abandon the children, Akira believes in what he has been told of his father. Being that nobody seems to know much about his father, he chooses to paint a heroic figure of an imagined man.

4. Like Father, Like Son (2013)

Kore-eda's most explicit exploration of the nature versus nurture debate is in “Like Father, Like Son”. In a contrived case, he gives us archetype characters to put his point across. But while giving us a slightly artificial scenario, he handles it in a natural way that offers no easy solutions.

With a nurse jealous of their wealth, she switches Ryota (Masaharu Fukuyama) and Midori's (Machiko Ono) new-born son with that of Yudai (Lily Franky) and Yukari's (Yoko Mari). Six years later, and the switch is revealed to both sets of parents; their respective son's Keita (Keita Ninomiya) and Ryusei (Shogen Hwang) now fully formed characters.

Ryota is upwardly mobile and dedicated to his work, more so than his homelife. He is old-fashioned in his approach, viewing his role as father as one of financial support. Conversely, Yudai is a handyman, DIY shop owner, whose work is his home, playful in his approach, offering his children love and entertainment more than money. In their own ways, they are both good fathers, but also bad. On discovering the switch, Yudai sees it as a ticket to financial stability in suing the hospital, though Ryota is much more reserved in this approach. His son Keita is a meek individual, doing as he is told and speaking only when spoken to. He does not see himself in his son, believing ‘now everything makes sense.' He wants a son to reflect his determined manner and will to succeed.

As the families experiment with weekend swaps of the two boys, Ryota gets insight into nature versus nurture. When sat in the car with him, his birth son Ryusei is a much more strong-willed character than he is used to. He talks back and does what he wants, rather than what Ryota tells him. He is a truer reflection of his personality, but is not the son that he desires. With Ryota dedicated to his work, Ryusei – with his strong personality – requires dedicated parenting that Yudai gives him. With his regular absence, Keita is the son that best fits his ways. He wants order in the limited family time he gives.

While believing traditions of the working father and blood is thicker than water, as his various attempts to take charge and handle the situation fail, Ryota begins to realise that people can't and won't simply do as he wants. Gradually he sees that parenting requires time and dedication to learn and understand each other, rather than setting strict rules.

5. After the Storm (2016)

Hiroshi Abe is Ryota, a world-weary novelist, who still claims his working as a private detective is research for his next book. The reality is he is a man going nowhere, unshaven and living in a tiny apartment, having been kicked-out by his wife Kyoko (Yoko Maki) and son Shingo (Taiyo Yoshizawa). He struggles to make his monthly child-support payments, looking for quick-money, though failing, as he does with much in life.

He is a classic case of a man showing interest in his family once they have left him, though his interest is purely selfish. He uses his detective skills to spy on Kyoko with her new boyfriend; and time spent with Shingo is to ask questions about his ex-wife's new man. He can't understand why she has left him for a man more seemingly bland and stable than him. But another comedic exchange shows exactly why.

Ryota's mother Yoshiko (Kirin Kiki) now lives alone in the projects in a tiny apartment, left nothing by her dead husband who had similar addiction and money problems as his son. Indeed, Ryota is more like his father than he will admit. When sat at the kitchen table, guests have to lean forward so Yoshiko can open the fridge door, how cramped her apartment is. This is the answer to Yoshiko's question to Kyoko as to why she didn't stay with Ryota. Her former mother-in-law is the woman she would become if she stayed with him, with the cycle likely to repeat to Shingo.

It is only on learning that his father was proud of his novelist son that Ryota can see the error of his ways. His father never offered him much, and so Ryota can use that as an excuse for his failures. If perhaps his father had the courage to have told him while he was alive, Ryota may not have made the same mistakes he did.

In “Our Little Sister” (2015), the siblings contemplate their father, stating he was a ‘kind man', only ‘a little useless.'

For the most part, fathers in Koreeda's films are both selfish and useless. The three-time character of Ryota (Hiroshi Abe in “Still Walking” (2008), the TV series “Going My Home” (2012) and “After the Storm”) serves as the best example of a Koreeda father: Selfishness and stubbornness has seen him continue to lead a bachelor lifestyle, despite being married with a child/stepchild. As such, as a father he has become somewhat useless, focusing more on his career failings, using his own father as an excuse for not achieving the success he perhaps could have.

Essentially, these are men not mature enough and ready to become fathers. The birth of a child does not necessarily mean the birth of a father; it is something they need to grow into over the years and after numerous mistakes. Fatherhood is very much on-the-job-learning and takes time. In the nature versus nurture debate that runs through his work, both will influence how a child will grow-up and the person they will become. But blood does not necessarily make a good father. Dedication, time and sacrifice are more important, and sometimes the children may have to find that elsewhere.