By Siria Falleroni

“Timeless Bottomless Bad Movie” also known as “Bad Movie” is a 1997 South Korean film directed by Jang Sun-woo, a renowned filmmaker recognized for his provocative and controversial works. The film won two awards from two important Asian film festivals, the Asian Film Award from the Tokyo International Film Festival and Busan International Film Festival's NETPAC Award.

Buy This Title

on Amazon by clicking on the image below

The premises that will shape the entirety of the film are evident right from the vibrant and colorful opening credits, set to the syncopated rhythm of punk-rock music: “Plot: not fixed. Starring: not fixed. Photography: not fixed. 1000 good movies, 1 bad”. With such a striking and thought-provoking overture, the director signals a certain rupture with traditional storytelling conventions, embracing a more rebellious and unpredictable narrative structure. The movie's manifesto immediately implies a rejection of rigid cinematic dogmas, while inviting the viewers to embark on a journey where the boundaries of storytelling, character development, and visual aesthetics are pushed to their limits.

“Bad Movie” does not betray its underlying values; it is what one imagines when thinking of a “bad” movie. The film was shot on 35mm and 16mm film, employing a semi-documentary style that is incredibly intricate to follow. Jang Sun-Woo's camera becomes a frenetic force, ceaselessly moving through the city of Seoul, much like its youthful inhabitants. The abrupt changes in locations, characters, and style immerse the viewer in the suburban chaos of the metropolis, akin to finding oneself at a hectic street intersection, on the verge of being almost struck by a car.

Follow our coverage of lesser known movies from Korea by clicking on the image below

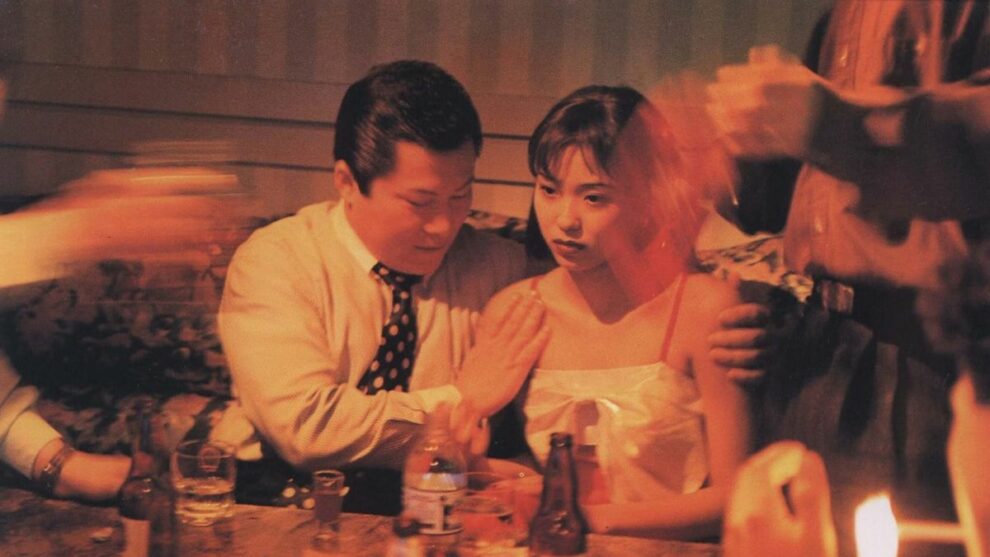

The most challenging aspect that significantly contributes to the complexity of understanding “Bad Movie” lies in its deliberately fragmented and chaotic structure. The film is divided into sub-chapters, such as “Sorrow of a Beggar”, “Why Did You Lie?” and “Robbing Middle-Aged Men”, featuring young rebels with whimsical nicknames like “Birdbrain”, “Mr. Potato”, and “Douchebag”. Given the absence of a defined plot, the viewer is transported into spontaneous glimpses of violence and ordinary madness within the Korean capital. We witness motorcycles speeding through the main streets of Seoul, conversations among the homeless, young girls engaging in prostitution, drug addiction, and promiscuous sexuality played out in cramped KTV establishments, urban vandalism, and theft. Those “bloody punks” that populate the two-and-a-half hours of this experimental work are precisely the antithesis of characters with whom one can empathize throughout the viewing experience. Their authentic subversive spirit ends up rendering them almost unbearable to see.

However, it is precisely in this process of emotional confrontation with the protagonists that we find ourselves victims of the trap devised by Jang Sun-woo. Isn't the director's purpose perhaps to bring to the forefront those individuals who are considered the discarded remnants of the metropolis, the forgotten ones, the defeated, and the outcasts? Perhaps the morally questionable characters in “Bad Movie” are so repugnant precisely because they are the failed product of the previous generation's shortcomings. The idiosyncratic nature of this group of youngsters is indeed connected to the existential boredom, rebellious spirit, and adrenaline-fueled thrill typical of any adolescence, but it is closely intertwined with the zeitgeist of 1990s South Korea.

Despite their flaws, these characters embody the consequences of a flawed society and raise pertinent questions about the underlying issues that perpetuate their liminal existence. The youth culture of the 1990s in South Korea was characterized by a blend of global and local influences. The music and entertainment industries were rapidly evolving, with new genres and the explosion of pop media culture. At the same time, Korean society was still grappling with certain social issues, such as economic inequality, the democratization of its political system, intergenerational tensions, and the debate surrounding modernization and the preservation of traditional culture. These themes and challenges were also reflected in the films and artworks of the time, which often explored the complexities of a society in transformation and the experiences of the youth. That being said, the movie's Achilles' heel remains the challenging comprehension of this socio-cultural backdrop to an eye hypothetically detached from the contemporary history of South Korea.

On the contrary, there are two main strengths in this experimental work. The first is the director's ability to play with the blurred boundaries of reality and fiction, even experimenting with brief inserts of animated cinema. While the film is founded on the premises of lack of technical preparation and the spontaneity of events, in one of the most disturbing final sequences, it is revealed that the protagonists are acting and staging themselves. The presence of a cameo by one of the most famous Korean actors, Song Kang-ho, portraying one of the homeless characters, also challenges the veracity of the initial statement. The second intriguing aspect is the choice of diegetic and extradiegetic music. The soundtrack selection, primarily consisting of independent songs, fully captures a glimpse of the underground and alternative life of the late 1990s. For example, two songs by the “Pippi Band”, a Korean alternative rock group, are included. The band gained notoriety when they were banned from television and radio for a year after a live broadcast incident where they spat on a television camera and made an offensive gesture towards it. Also, some tracks by the popular band “Turbo”, such as “Love is… (3+3=0)” and “Twist King”, are included.

In conclusion, “Timeless Bottomless Bad Movie” represents a milestone in the history of South Korean cinema for its iconoclastic style, its alternative aesthetic, and the significance of the generational themes it addresses. However, it struggles to transcend into a more “universal” cinematic instance.