Proof of the Man (Junya Sato 1977)

In “Proof of the Man”, Matsuda plays Detective Koichiro Munesue, whose investigation of the murder of an African-American in Tokyo takes him to New York City, where he works with his US counterpart, Ken Shuftan (George Kennedy). The partnership itself torments Munesue, as Shuftan's seahorse tattoo identifies him as one of the US soldiers during the Occupation, who beat Munesue's father to death when he had tried to save a Japanese woman from a gang rape.

The flashbacks to that awful scene attack Munesue frequently (Fig. 30), a terrible recurrent trauma made somewhat more colossal given that a man Munesue's age in 1977 would not have been as old as the boy who witnessed the outrage.

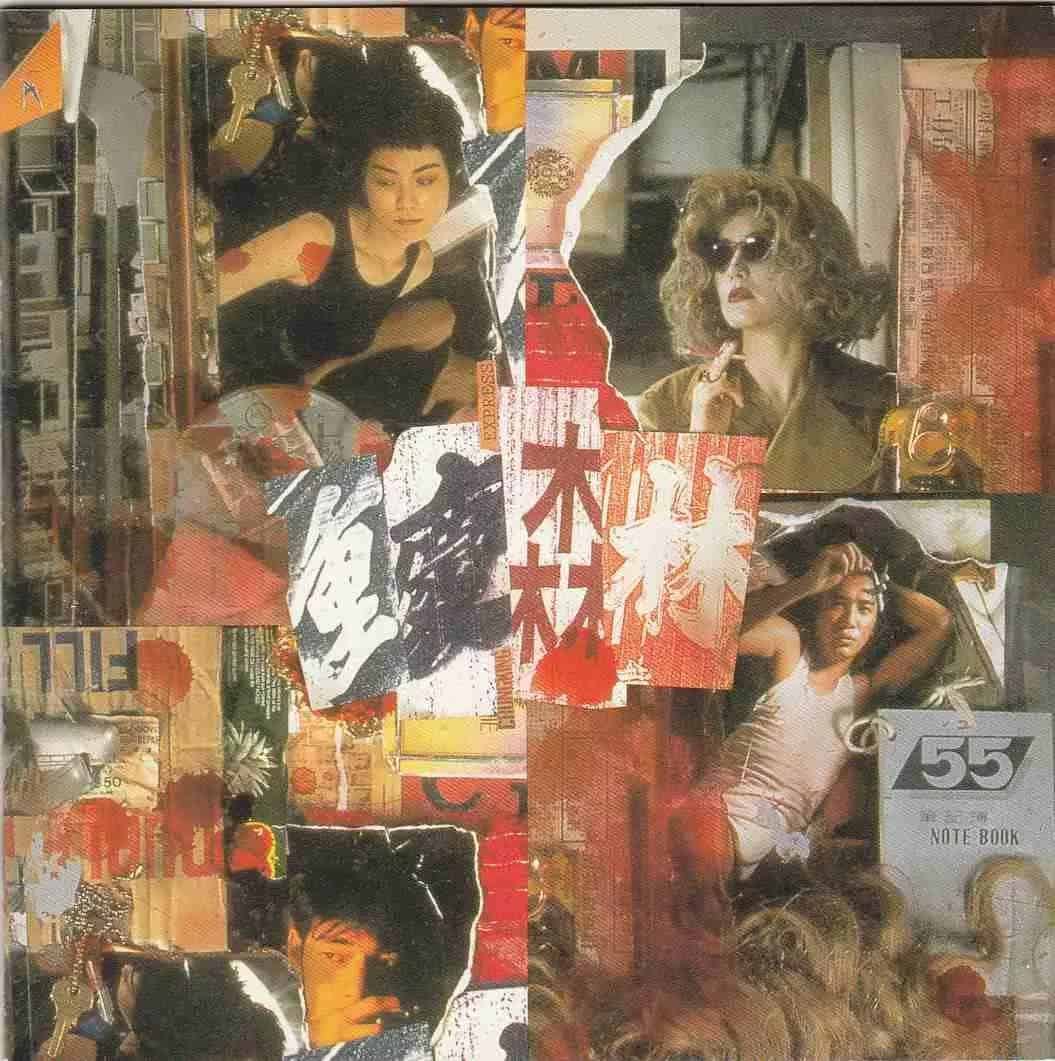

The Beast to Die (Toru Matsukawa, 1980)

The film opens with the beginning of a crime spree that becomes increasingly violent. We see Kunihiko Date (Yusaku Matsuda) who embarks on it, so the mystery is not who did it but why. And that question is revealed only toward the end of the film and even then, the revelation comes in partial accounts. Date had been a foreign correspondent and photographer, specializing in reporting from war zones. He witnessed and graphically recorded the horrendous crimes committed in the conflicts – massacres, torture, and general butchery. But his employers found his images too extreme, and he was fired and essentially blacklisted from the field. As Date becomes increasingly deranged, his internal life is represented by montages of his photographs of atrocities. The acts he had witnessed and their suppression led to his psychological collapse. He became the horrors he had internalized; his memories and their erasure led to his identification with the perpetrators he documented (Figures. 31-32). Like Munesue, Date fell victim to memories that could not be rationalized.

Black Rain (Ridley Scott 1989)

In 1989, Yusaku Matsuda appeared in a film with one of his idols, Ken Takakura. As I mentioned in Part One, Matsuda often thought of the 100 plus films Takakura had starred in, and wondered if he still had time to star in so many. He answered his own question – given the changes in the film industry it would not be possible, he was the man who came too late. And his appearance in “Black Rain” came too late for Matsuda altogether. Shortly before filming started, Matsuda was diagnosed with cancer, but he refused chemo as it would interfere with the shooting schedule. And that decision most likely cost him his life.

Matsuda's performance in the film is stunning. In his first appearance in the bar in New York City, he seems to materialize out of nowhere, a kind of phantom in the flesh with his own agenda (Fig. 33).

This arrival has the majesty of an etude in a minor key, since it has made Matsuda forever too late – an arrival that is also a departure, and he leaves his image indelibly on the film, a memory, a Memento Mori.

I have viewed The Game Trilogy multiple times and most of the other films you mentioned. Your Zones of Terror analogy for The Game Trilogy resonates in particular, and I like your comments about the time and scene dissonances and the memory on memory elements of the trilogy.

Narumi is indeed a monster, but he lives in a world of monsters greater than himself. He plays by the rules of the game: he takes the contract and he fulfills it as best he can. It is the monsters greater than himself who interfere with, abruptly change or violate the rules. Those monsters are engaged in organized crime, violence and corruption that affects Japanese society as a whole. Nurumi is not killing innocent, ordinary citizens. He doesn’t attack or kill any of the mahjong players who he suspects of cheating, even when they seriously beat him or later for revenge. Narumi stays within the rules of the game, including payback for those who violate the rules.

It’s not a secret Japanese society has long been male-oriented and male dominant. Whether we agree with that or not, the Trilogy was filmed 45 years ago when those attitudes were still relatively unchallenged. And the majority of the women Narumi deals with in the Trilogy are not innocent: they are duplicitous, scheming accomplices of organized brutal crime.

I appreciated your comments about the correspondence between Narumi, the man without a history, and Yusaku Matsuda’s own personal history. An actor with silenced history playing a character with no history. Was that coincidence? I think not. Both the director and Matsuda had to be fully alert to that element. Certainly in the Trilogy, Narumi’s lack of back story is a magnet that pulls our focus and interest in the character more effectively than the inclusion of any back story in the film would.

Thanks for this series on Yusaku Matsuda. I look forward eagerly to the next installment.

thank you, Link. I really appreciate the depth and engagement of your reading.