By Earl Jackson

In 1939, Sadaho Maeda was born in Fukuoka, the third of five children to an Imperial Army pilot and a retired track-and field runner. While still a toddler, the family moved to Chiba Prefecture where Sadaho grew up. Perhaps that location was the inspiration of the publicity people at Toei in 1960 to rename this “new face” – Shin'ichi Chiba. He became a teen favorite as a “funky hat” detective in a series directed by Kinji Fukasaku, and then gained another fan base with his pursuit of serious martial arts training. Chiba was already a powerhouse by the time the three “Street Fighter” films in 1974 introduced him to the world as Sonny Chiba.

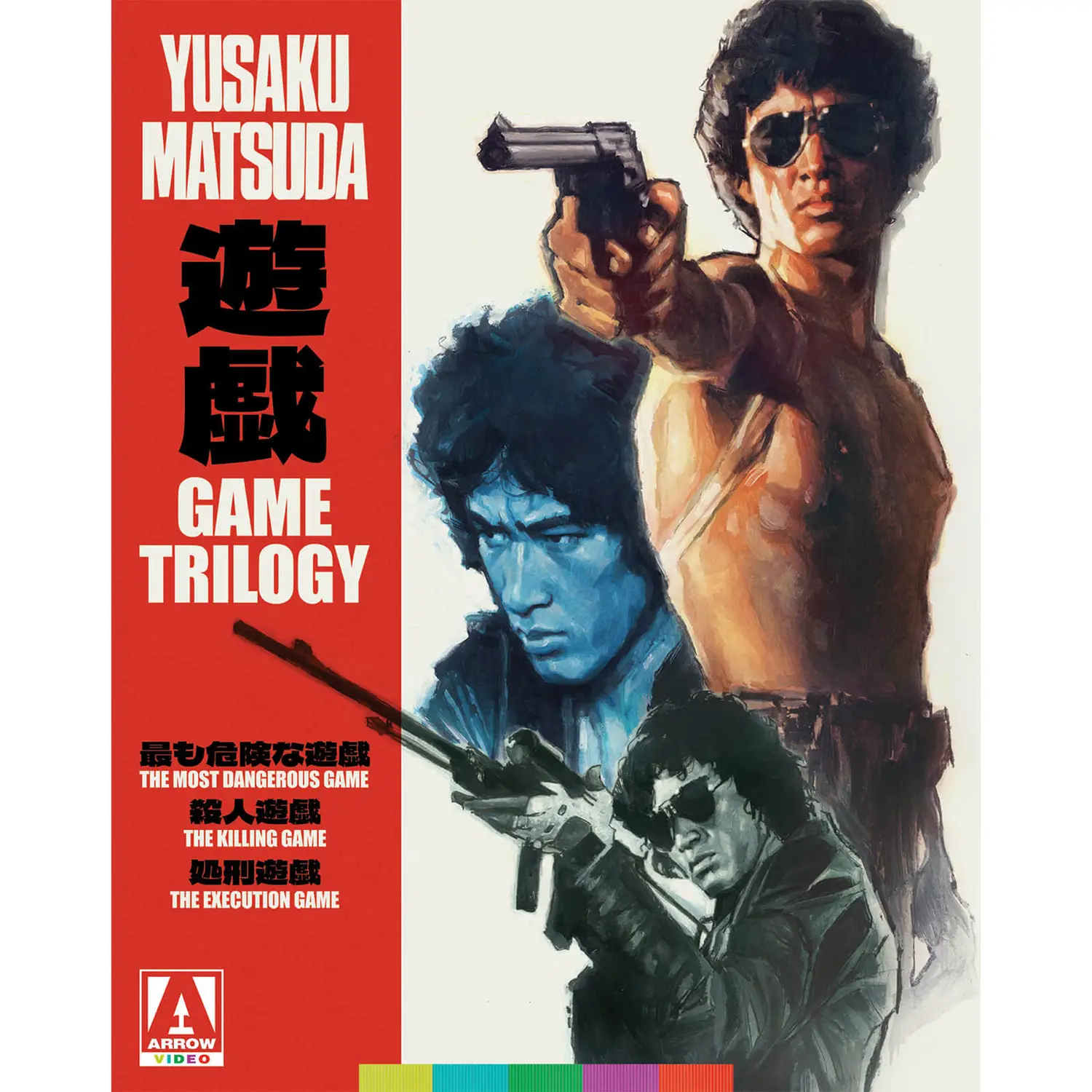

If the world had granted him more time, Toru Murakawa's “Game Trilogy” in 1978-1979, might have done the same for Yusaku Matsuda. Although it was always already too late for Matsuda, we now have time to reassess the trilogy in all its problematic, messy, and contradictory glory as a significant part of Japanese cinema history, and a legacy cut short.

Buy This Title

by clicking on the image below

The Game Trilogy

One of the challenges to a full engagement with the trilogy is its mode of masculinity. It might help to consider that not so much a core belief as communication noise. The director Toru Murakawa's description of the risk making a film constitutes, helpfully encapsulates the contradictions in the masculine display: “One makes a film in order for it to be seen. . . . It's like pulling our matanki マタンキ out.”

Although context makes it relatively easy to guess, only those who were adolescents in the 1970s would know the term matanki. The term was coined and then frequently used by characters in the manga “Dr. Toilet” that appeared in the Weekly Shonen Jump from 1970-1977. It is kintama backwards. Kintama is slang for testicles. Testicles metaphorically signify masculine power, while in physiological reality testicles are the most vulnerable part of male anatomy. In a kind of rhetorical parallel, in using matanki, Murakawa describes exposing the testicles with a word that conceals that exposure, while also confessing the childishness of such bravado. Narumi's loner persona and skill in remorseless killing are presented with a similar subliminal undermining of the depiction.

The “Game Trilogy” is based on a very simple premise: Shuhei Narumi (Yusaku Matsuda) is a highly skilled hitman who will kill a target for 20 million won. Narumi is yet another character without a backstory: it is never explained where he acquired his seemingly inexhaustible arsenal; how he acquired his deadly skills; or why he has chosen this life. He accepts an assignment without question – until he suspects a betrayal or complication from those who hired him.

These simple transactions with this relatively one-dimensional character, however, are enacted in a world that operates on its own logic: actions do not necessarily have consequences; random occurrences are interlaced with coincidences that seem to suggest an inexorable fate at work; motivations range from fluid to contradictory – all culminating in narratives that feel like Seijun Suzuki without the whimsy. The only drive toward coherence is the game, the contract between client and killer, and even this compact is unstable and volatile.

The trilogy should be enjoyed thoroughly for its own rhapsodic action and suspense, and my reflections on the film won't interfere with those thrills on offer. My readings of the films will be only partial and more interested in the richness of the text than the twists and turns of plot. I will focus on a duality between Narumi's negotiations with and against the world of the game and the relation of the Matsuda image to the mechanisms of the film as film. In “A Most Dangerous Game”, I will examine the world introduced in the narrative and the status of the film as part of Japanese cinema history in its casting. In “Killing Game”, I will look at the dissonance between Narumi's silence and Matsuda's voice. In “Execution Game”, I will consider the looping of memory. I will not expose the full complexities of the games as that would involve divulging spoilers. And I will only go into a plot summary for the first film as that one makes explicit the template of terror zones that figure in all three films.

The Most Dangerous Game (1978)

The world of Shohei Narumi is introduced in a sequence whose cross-cutting creates a temporal dissonance. The film opens with police discovering the body of the president of Tonichi Heavy Industries, who had been kidnapped (Fig 1).

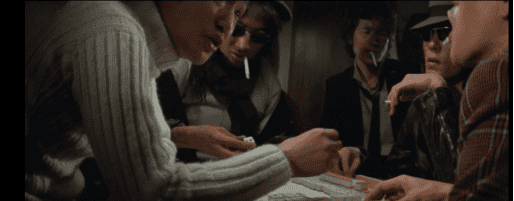

There is a linear progression of the close-up of the body to the newspaper article. Then there is a cut to a mahjong game where Narumi is losing (Fig 2).

The other players represent a glimpse of Japanese film history, from veteran character actor Hyoe Enoki to rising young stars, Kyohei Shibata and Renji Ishibashi. And looking on but not interacting is singer/composer Uchida Yuya. By not participating, he essentially appears as himself (reminiscent of the presence of Edie Sedgwick in “Vinyl” (Andy Warhol 1965), thus lending the endorsement of the Japanese alternative music/art scene. The assistant director (for this film and for “Killing Game”), Yoichi Sai, moreover, would make his directorial debut in 1983 with “Mosquito on the Tenth Floor”. And after some impressive crime films dealing with Okinawan politics, he would “come out” as a zainichi Korean director with “All Under the Moon” in 1993 and would continue that important intervention with “Blood and Bone” (2004) and his Korean film, “Soo” (2007).

The film cuts to another report of an executive kidnapping, Nakamura, the vice president of Godai Conglomerate, showing the special forces running out of their headquarters, followed by another newspaper article. And then a return to the mahjong game, and another cut to a third kidnapping -this time showing the actual act. The parallels cannot be simultaneous as every segment regarding the crimes entails a considerable amount of time passing – certainly at least two days if not more – while the clothes on the players mark the mahjong game as one continuous event. The parallels end with Narumi losing badly, unable to pay up, and accusing the others of cheating. They beat him badly and as he was recovering he was called into the offices of Tonichi Electronics, by its president, Kohinata (Asao Uchida).

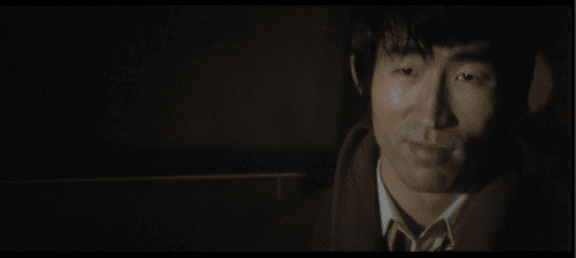

Uchida figures on both levels of the film. In the narrative, he makes the connection between the two until now unrelated opening sequences. He hires Narumi to rescue Nanjo, the victim of the third kidnapping, his son-in-law and explains the plot -in both senses of the story-so-far and the conspiracy behind the crimes (Fig.3).

According to Uchida, Godai and Tonichi Electronics were competing for a contract to create and maintain an air defense system over Japan. The kidnappings were only a ruse to murder Tonichi executives key to the project. Godai apparently conspired to kidnap its own VP to cover up their actions. Furthermore, the power behind Godai is criminal overlord fixer, Adachi Seishiro (Bontaro Miake). On the other level, both Uchida and Miake are grand old men of the yakuza film. Uchida is immediately recognizable which also foreshadows his untrustworthiness, while his filmography further embeds the film within the genre's legacy.

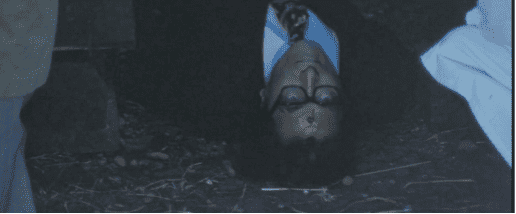

The game goes awry when one of the kidnappers fatally shoots the hostage as Narumi was carrying him to freedom. But it turns out this was only a test, and Kohinata actually wants Narumi to kill Adachi, one of the many instances in which the game changes rules and motivations. But as Narumi prepares for the real assignment, he himself is captured and tortured by a cabal of rogue police protecting Adachi, led by detective Katsuragi (Ichiro Araki). (Fig. 4)

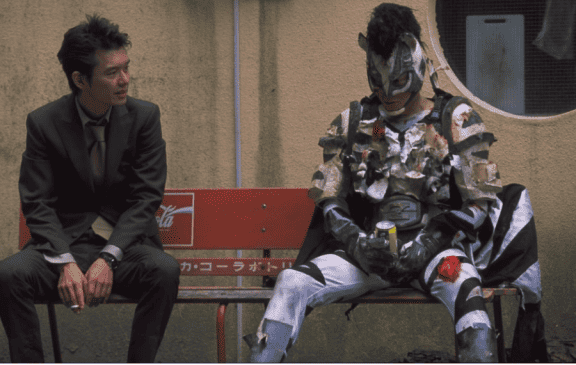

Araki's presence again integrates the legacy actors with the counter culture. Araki is a well-known singer and composer as well as actor who had worked with major “outlaw” directors Teruo Ishii and Nagisa Oshima. In fact, Araki's starring role as sex-obsessed student in Oshima's “Sing a Song of Sex” (1967) lends him a kind of decadent air, a sleaziness amplified by the recurrent reference to his infected finger, an infection that suggests an STD. His dogged pursuit of Narumi and his signs of physical corruption will be revised in the figure of rampant xenophobe Defense Agency officer Oikawa (Atsuro Watabe) in “Zebraman” (Takashi Miike 2004) who led a campaign to erase all forms of “difference” from the national body while he himself writhed in itchy agony from an infestation of pubic crab lice (Fig. 5)

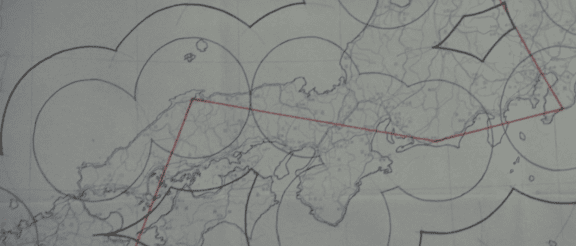

The key to the specific mode of anxiety that drives not only the first film but all three is figured in Kohinata's description of the national security system at the heart of his conflict with Adachi. His description is illustrated by a bizarre montage. The most significant image, however, is the map of Japan (Fig. 6). The security system would monitor the skies for an enemy attack. Japan, however, has not had a military for 33 years in 1978, so it is not clear what this system could do defensively. The map transforms Japan into zones of terror – sky-borne terrors that the nation knows very well -from the fire bombing of Tokyo to the atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

I have viewed The Game Trilogy multiple times and most of the other films you mentioned. Your Zones of Terror analogy for The Game Trilogy resonates in particular, and I like your comments about the time and scene dissonances and the memory on memory elements of the trilogy.

Narumi is indeed a monster, but he lives in a world of monsters greater than himself. He plays by the rules of the game: he takes the contract and he fulfills it as best he can. It is the monsters greater than himself who interfere with, abruptly change or violate the rules. Those monsters are engaged in organized crime, violence and corruption that affects Japanese society as a whole. Nurumi is not killing innocent, ordinary citizens. He doesn’t attack or kill any of the mahjong players who he suspects of cheating, even when they seriously beat him or later for revenge. Narumi stays within the rules of the game, including payback for those who violate the rules.

It’s not a secret Japanese society has long been male-oriented and male dominant. Whether we agree with that or not, the Trilogy was filmed 45 years ago when those attitudes were still relatively unchallenged. And the majority of the women Narumi deals with in the Trilogy are not innocent: they are duplicitous, scheming accomplices of organized brutal crime.

I appreciated your comments about the correspondence between Narumi, the man without a history, and Yusaku Matsuda’s own personal history. An actor with silenced history playing a character with no history. Was that coincidence? I think not. Both the director and Matsuda had to be fully alert to that element. Certainly in the Trilogy, Narumi’s lack of back story is a magnet that pulls our focus and interest in the character more effectively than the inclusion of any back story in the film would.

Thanks for this series on Yusaku Matsuda. I look forward eagerly to the next installment.

thank you, Link. I really appreciate the depth and engagement of your reading.