With a second Japanese court recently ruling the ban on same-sex marriage as unconstitutional, there is no more appropriate time to dissect the different facets of the lives and rights of Japanese queer people than now. In the documentary “A Son” directed by Ryuichi Shimada, that facet covers the concept of family, of how a gay man is accepted by his family and in return, on how he creates his own family himself.

A Son is screening at Nippon Connection

But then, it doesn't stop there. By all intents and purposes, “A Son” is also about Japan's flawed foster system, its institutions and the lifelong impacts that they could have on children whose concept of family has always been challenged and for some, even damaged.

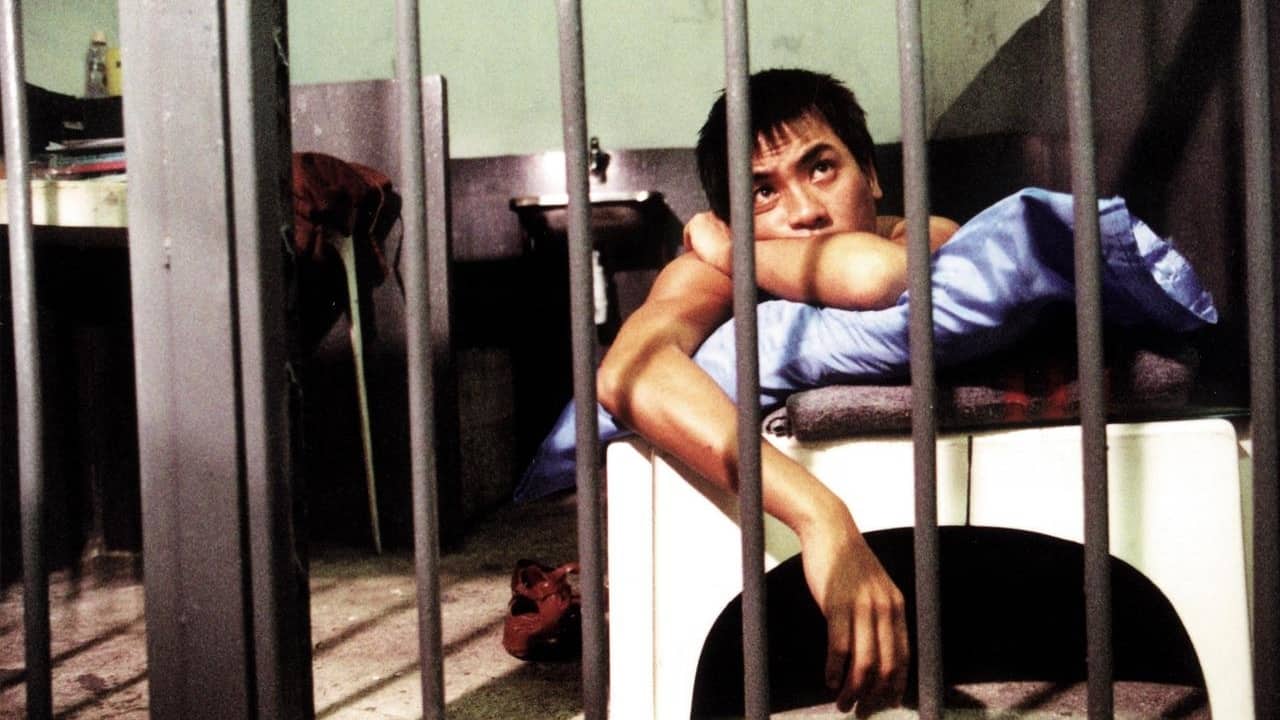

The documentary focuses on Yuki Amiya, a gay man who works at an organization which helps young people find their footing in the society after having to mandatorily leave foster homes after reaching a certain age. Amiya adopts Wataru, a product of such system who has also seen his fill of detention facilities, having committed some felonies. Wataru seems detached but is very passionate about turning his life around, with him saying in one of the most memorable moments in the film that he does not want his past to define who he could be in the future.

This is the main driver behind Wataru's decision to accept Yuki's offer to adopt him. As for Yuki, the way the people around him – particularly his colleagues – react to the news of him being a father is telling of how society in general can judge gay men as groomers and completely incapable of adopting a younger man without any sexual intentions. His workmates, some of whom are gay themselves, banter about it, but the jokes unveil deep-seated prejudices and hurtful stereotypes toward members of the LGBTQI community, as if they are incapable of being decent parents.

Even with this, however, Yuki's own family proves that amid such discriminatory beliefs, parents will only and always believe in you. In a heartfelt scene, Yuki's father, with quiet tears in his eyes, tells Wataru that he believes in him because his son does. He says this after Wataru, even with him being adopted by a gay man, admits that he remains traditional and conventional in his beliefs, saying he may not have the heart to just be like Yuki's father if ever he finds himself having gay children in the future.

This is just one of the many tensions and disparities which the documentary captures. It also tries to see how foster parents feel, placing their own insecurities alongside the uncertainty that grips young people once they leave shelters and find themselves as either alone, or suddenly having to adjust and adapt in a setting that is strange to them, that of having a “family.”

The ultimate tension and irony which “A Son” shows, however, is that while finding a family and being a family are things that bring happiness, do not always lead to a happy ending. Shimada conveys this through an accidental symbol, a metaphor which stands for both beginnings and goodbyes. But maybe, that's not the point. Maybe the point is that just in between, lives intersect, paths cross; so much so that once, there was a father. Once, there was a son. Once there was a family. Once.