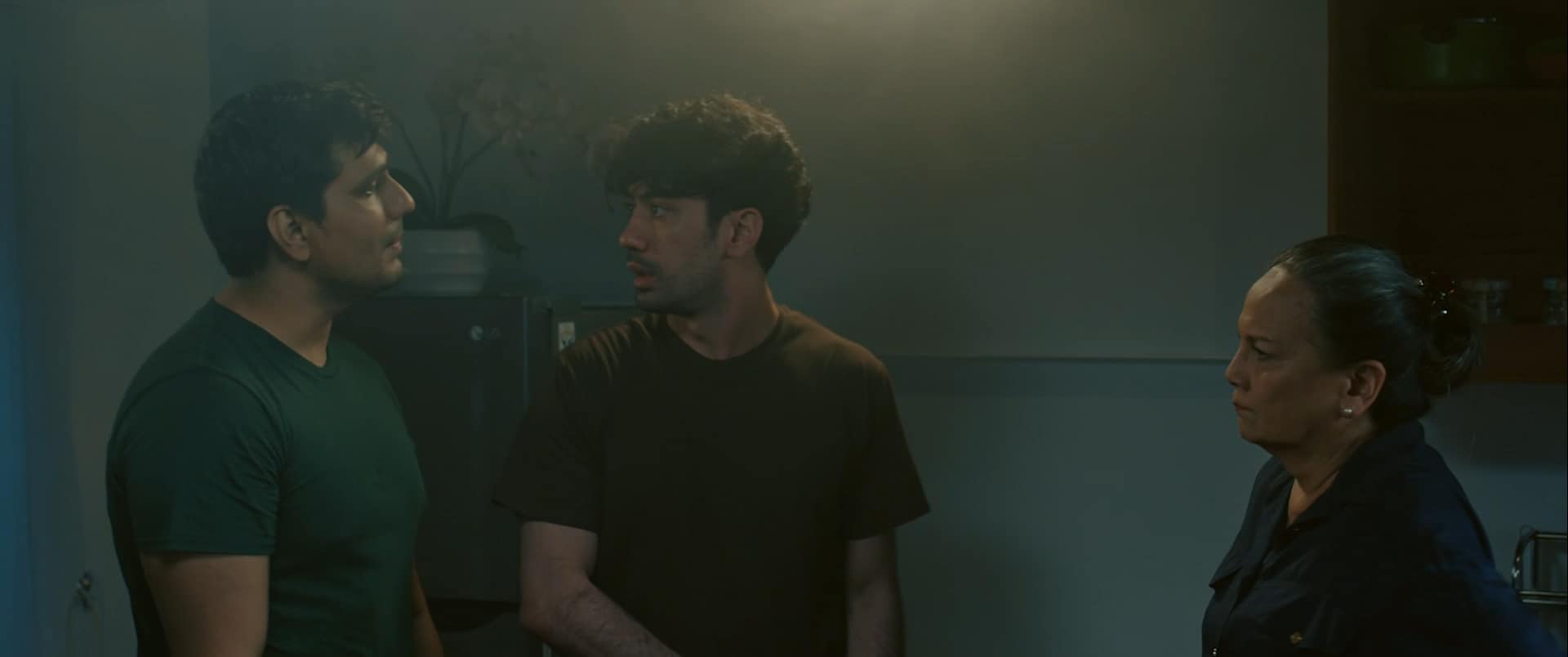

What repercussions are there for he who shows up unannounced, with a metaphorical tail between his legs, pleading forgiveness for the unforgivable violation his actions have amounted to? What then for she whose self-worth, dignity, and vulnerability have but all been erased by just this one action alone? A pitiful interaction intent on invading her last bastion of security, Jeong-sun (Kim Keum-soon) stands wounded and silent as Yeong-su (Jo Hyun-wu) bargains to have charges made against him dropped for the betterment of his own welfare. It is a mere breath in Jeong Ji-hye's immersive feature-length debut but a breath wrought in anguish, a painful inhalation with zero catharses in its exhalation, just one of many fleeting moments where the totality far outweighs the extent of ‘Jeong-sun's already fraught narrative.

Jeong-sun is screening at Women Direct. Korean Indies! Korean Women Independent Film Series

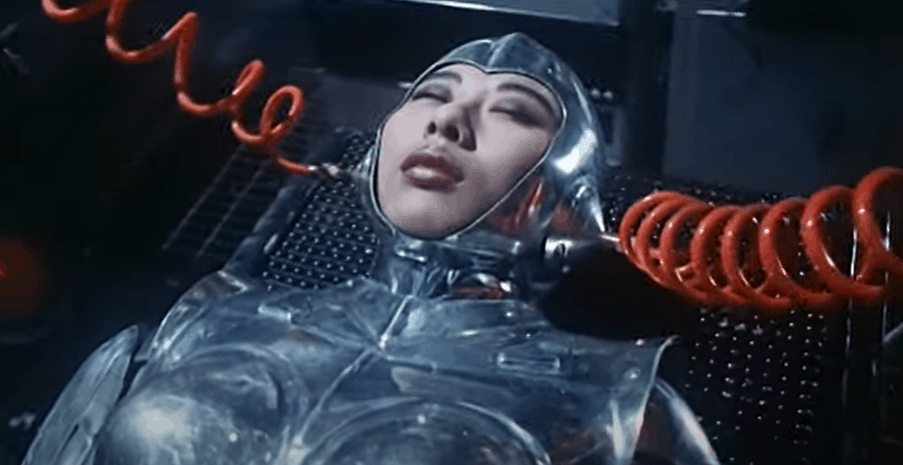

Jeong-sun, a middle-aged single mother, lives an uneventful life working nights at a packing factory. She finds simple yet sustaining pleasures in interacting with her colleagues; their cheekiness knows no bounds both in and out of the workplace. When Yeong-su joins the factory, she becomes immediately drawn to him and soon the pair begin a tender, affectionate romance away from the prying eyes of their younger, more judgmental colleagues. Never wishing to be the center of attention, this suits Jeong-sun more than it does her new partner who takes this decision personally. But when he shares an intimate video consensually taken of her singing and dancing to his arrogant supervisor, a video which soon spreads beyond the factory, Jeong-sun is suddenly thrust into a humiliating position; shaken to her core, she finds her entire existence thrown into disrepair.

Crucially, from the moment Jeong-sun realizes her unsettling predicament, a painful moment read so visibly upon her face, Ji-hye's meticulous world-being pays off. Jeong-sun's mundane microcosm – a close-knit world built on security and small comforts – shrinks to unfathomable dimensions and not even a locked door can be presumed a safe measure against an outside world that has seen far too much. As the walls further close in on her stability her control over basic functionality spirals further until it reaches a boiling point, steamrolling into an emotional collision with her proactively assertive daughter (Yoon Geumseon-ah) who has taken charge of fruitlessly delivering justice. Ji-hye's pure fixation on her story's unlikely heroine, almost entirely from her perspective, unravels a seething intensity punctuated by the hollow desperation all too many women have long suffered.

As the police undertake their investigation and produce their findings to Jeong-sun, one thing remains true among the hearsay: in cases such as these, the victim, whenever allegations are made, seldom comes out the victor. Keum-soon, standing in the shoes of a woman whose very essence has drained from her being, leaves an indelible impression; her transformation from playfully mischievous wallflower to empty vessel is a brutally harrowing experience which Keum-soon sensitively encapsulates, harnessing her compassionate nature and reeling from the pain of which she has been inflicted. Hyun-wu's embodiment of patheticism, on the other hand, is unmistakable: Yeong-su's descent into self-victimisation and inherent unlikability is executed with such blood-boiling verisimilitude, that Jeong-sun's torment feels all the more real; it is a despicable role but one in which Hyun-wu delivers what is deserved. Between the two of them, ‘Jeong-sun' resonates on such a personal level with its humanity done justice.

There is an extraordinary dullness in the world ‘Jeong-sun' occupies, its colors drab and muted, its conversations stilted and uninteresting, and its enjoyment far removed from the cinematic. Both Ji-hye and cinematographer Jung Jin-hyuk bring this world as close to real life as possible; Kim Gyeol captures the slowing stillness of this unexaggerated life flawlessly, resulting in its dramatic turning point landing closer to home than it deserves. The further along the film goes, Jin-hyuk's framing becomes entirely claustrophobic, with both Jeong-sun and the audience suffocating under the unbearable magnitude of her situation; even as she takes steps to regain what is rightfully hers, this framing refuses to broaden. Though there is a lack of a score, what Choi Hye-ri and Hwang Hyeon-tae achieve softens the blow each calculated breath lands, ultimately avoiding drenching the film with superfluous sadness.

Gapjil – the essence of South Korea's toxic work culture so entrenched within its society, its victims predominantly women and gig workers – has raised its grotesque head in the post-pandemic return to the office high enough for the world beyond the country's borders to take notice. Devoid of sensationalism, Jeong-sun's futile insignificance in the grand scheme of the Korean narrative, an oft-overlooked and invisible woman, not only amplifies the country's struggle with ageism and sexism further but also her story's universality. Not unlike the gradual emergence of feminism and the MeToo movement at the tail-end of the previous decade, Jeong-sun's regaining control of her own narrative is slow and arduous, yet in the end, she leaves behind something which will no doubt keep her colleagues talking for years to come.