While the Golden Age of Korean cinema is considered to be the period from 1955 to 1972, and the Renaissance that essentially lasts until today starting with the modern blockbuster Shiri, which was released in 1999, there is also another period in local cinema, 1988-1996, that saw the emergence of a number of directors who truly pushed the boundaries of what was considered Korean cinema at the time, essentially paving the way for what followed next. Benefitting from the loosening of censorship and overall control in the industry in terms of topics and themes, directors such as Kim Dong-won, Lee Myung-se, Park Kwang-soo and Chung Ji-young came up with movies that took a realistic look at some of the most crucial events of local history, while also criticizing a number of issues the system faced at the time. The split of the two Koreas, the Gwangju massacre and the authoritarian rule, capitalism, worker's rights, education, LGBT, tradition, patriarchy, the Olympic games, and a number of other topics were all criticized by a number of movies, which additionally, and surprisingly, were occasionally also box-office hits, with “Chilsu and Mansu” emerging as a prime sample.

I will not dwell in the history any more, instead I would urge you to read the articles featuring in the Korean Film Council page, which explain the whole phenomenon as thoroughly as possible. What I will do, though, is present a number of films that highlight the phenomenon in all its glory, in an article that will continue to expand as we deal with more of the films of the era. “A Petal” was released one year later, but considering when it was actually shot and its overall contextual approach, it is definitely part of this list.

1. Sa Bangji (Song Kyung-shik, 1988)

Song Kyung-shik directs a movie that includes almost every favorite aspect of Korean audiences, with the melodrama, the episodic structure and the odyssey-like story moving towards a distinct crowd-pleasing path. At the same time though, there are two elements that make the movie stand completely apart from almost any other local production. Obviously, the first one is the main character, with this probably being the first time an hermaphrodite is the protagonist of a Korean movie. Song highlights the difficulties her life presents as soon as people discover her true identity, with words like ‘ monster ‘ and ‘abomination' setting the tone quite eloquently here, with the drama emerging mostly from this root.

The second is the erotic, which begins as simple sensuality before it becomes more and more steamy, with the sex scenes following a homosexual path, which can also be perceived as a comment regarding the subject, particularly during the era. The way these scenes change as the story progresses is also interesting, as the artistic first ones soon give their stead to more titillating ones, with the last pointing somewhere close to soft-porno, despite its briefness and lack of nudity. Also of interest is the less-than-a-second one that presents Sa Bangji's member, in a moment that definitely remains on the mind of the viewer.

2. Gagman (Lee Myung-se, 1988)

The episodic narrative of the film, that seems to revolve around the “cinema imitates life and vice versa” concept is rather unusual, dominated by elements of slapstick and absurdness, all the while retaining a sense of disorientation due to the thinning of the borders between fantasy (cinema if you prefer) and reality. Through this tactic, Lee makes a number of comments regarding the movie industry, with his most obvious (and most ironic) being the one when the director exclaims, “Who would make a real movie in the 21st century?” However, the gag-humor that seems to dominate the film (the scene where the girl is singing Suzie Q on stage and the director and the barber dance is a great sample, and one of the most entertaining sequences in the film) allows the story to flow quite nicely, particularly because Lee does not seem to take himself and his movie overly seriously. This flow benefits the most by Kim Hyeon-I's (another Bae Chang-ho regular) editing, who connects the various scenes with artfulness, while retaining a rather fast pace that suits the film's aesthetics perfectly.

Another central point in the narrative is the characters and their connection, which revolves around the ability of Lee Jong-se to draw the other two into his fantasies. And if the barber, who also represents the eagerness Koreans felt at the time for anything American, was keen to do so from the beginning, the way the street smart Seon-yeong falls under his spell is impressive, with him drawing her in gradually, through his rather appealing paranoia.

3. The Age of Success (Jang Sun-woo, 1988)

Jang Sun-woo presents a critique of the extreme capitalism that was permeating a Korea that was handling the Olympic games at the time, where the continuous financial progress had made the pursuit of sales, and subsequently money, a one way street for a plethora of people. The tactics the company used in order to overcome one another are satirized in the most hilarious but also pointed way. The continuous increase of price off in products in convenience stores, the sexualization of the advertisements, the inclusion of technology that seems at least far fetched are just a few of the tricks presented here, essentially presenting the corporate men and their tactics as utterly ridiculous. The behavior of the higher ups, and their demand for constant results no matter what, is also presented under the same prism, essentially deeming all of them as hateful, and quite sad caricatures, even if the “sadness” gets bigger the lower one is placed in the corporate ladder.

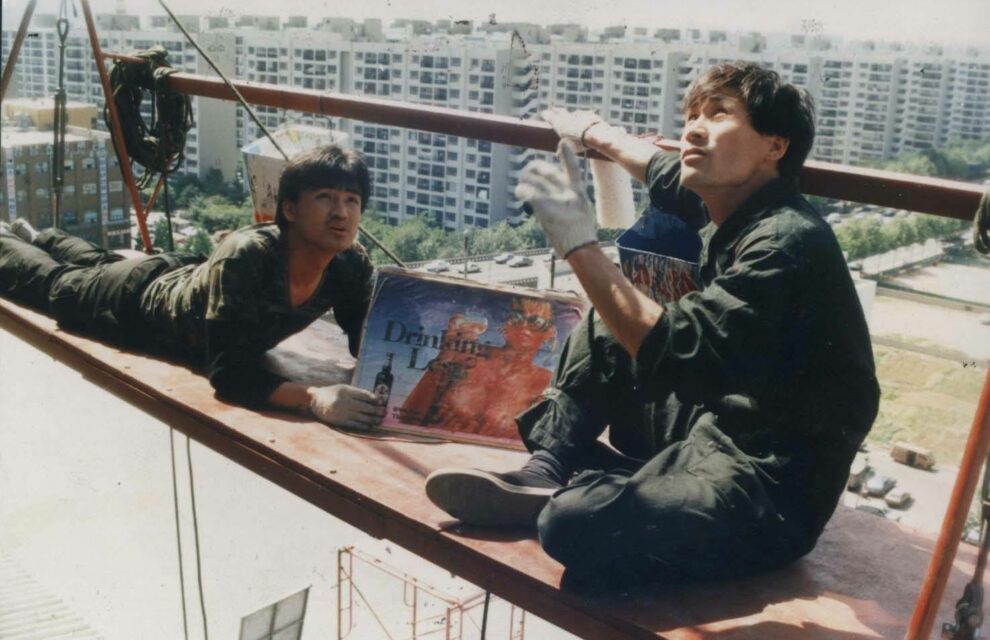

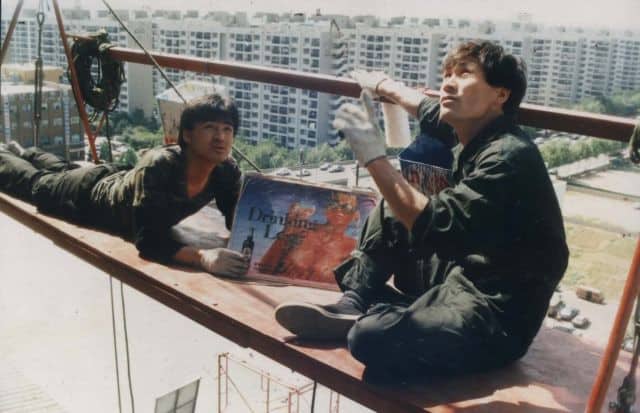

4. Chilsu and Mansu (Park Kwang-soo, 1988)

Park Kwang-soo directs a film that uses an unlikely base, since the way the two become friends borders on the surrealistic (one can easily see the impact the film had on Kim Ki-duk's “Bad Guy”) in order to present a number of sociopolitical comments about the era, which become much more intense as the story progresses. In that fashion, initially the film deals with the turning of the Koreans towards western civilization and particularly the US (English language, movies, clothes, video games, music, and almost every aspect of the then American pop culture), and the newly realized social inequality and worker's rights, as expressed in the scene where Man-su quits. As the story progresses though, the comments become more “serious” and intense, regarding the practices of the then regime towards political dissidents, which even extends to their children, as we witness in Man-su's life story. The impact of the US is represented by Chil-su's life , regarding both his family's story and his will to move to Miami.