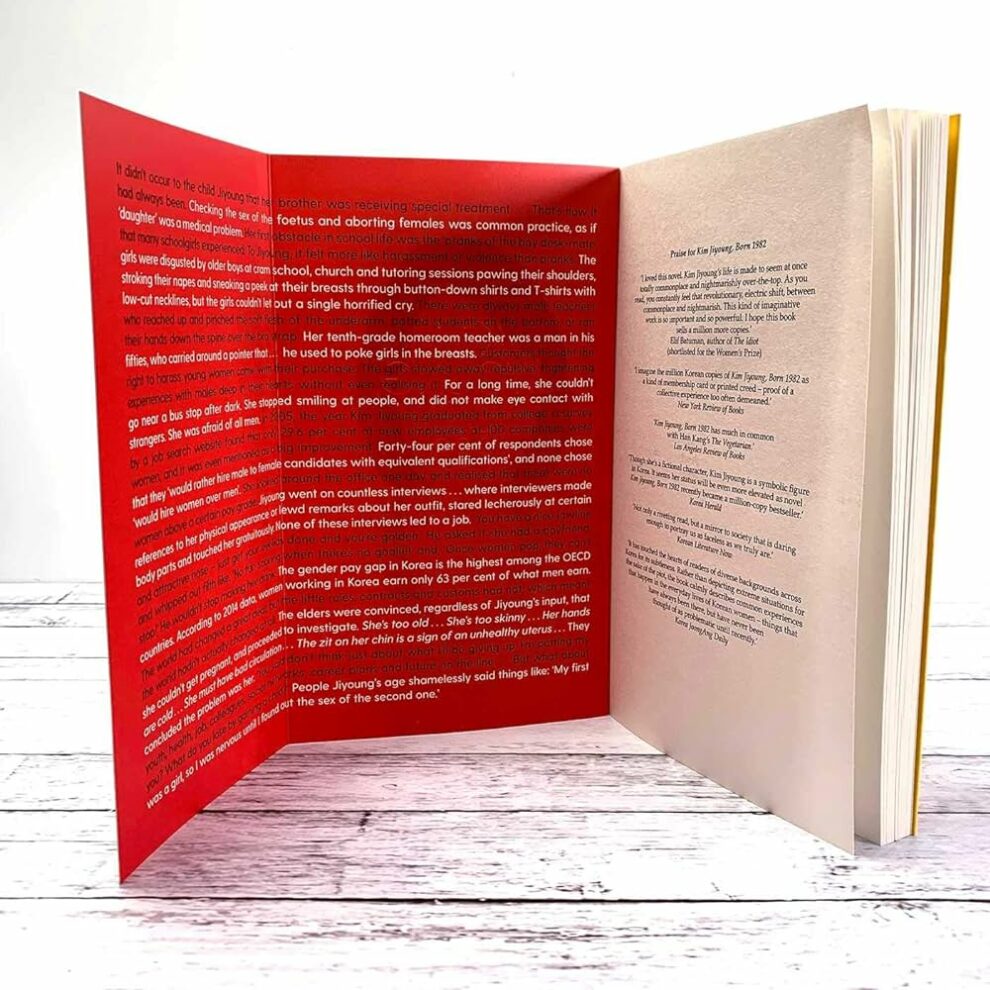

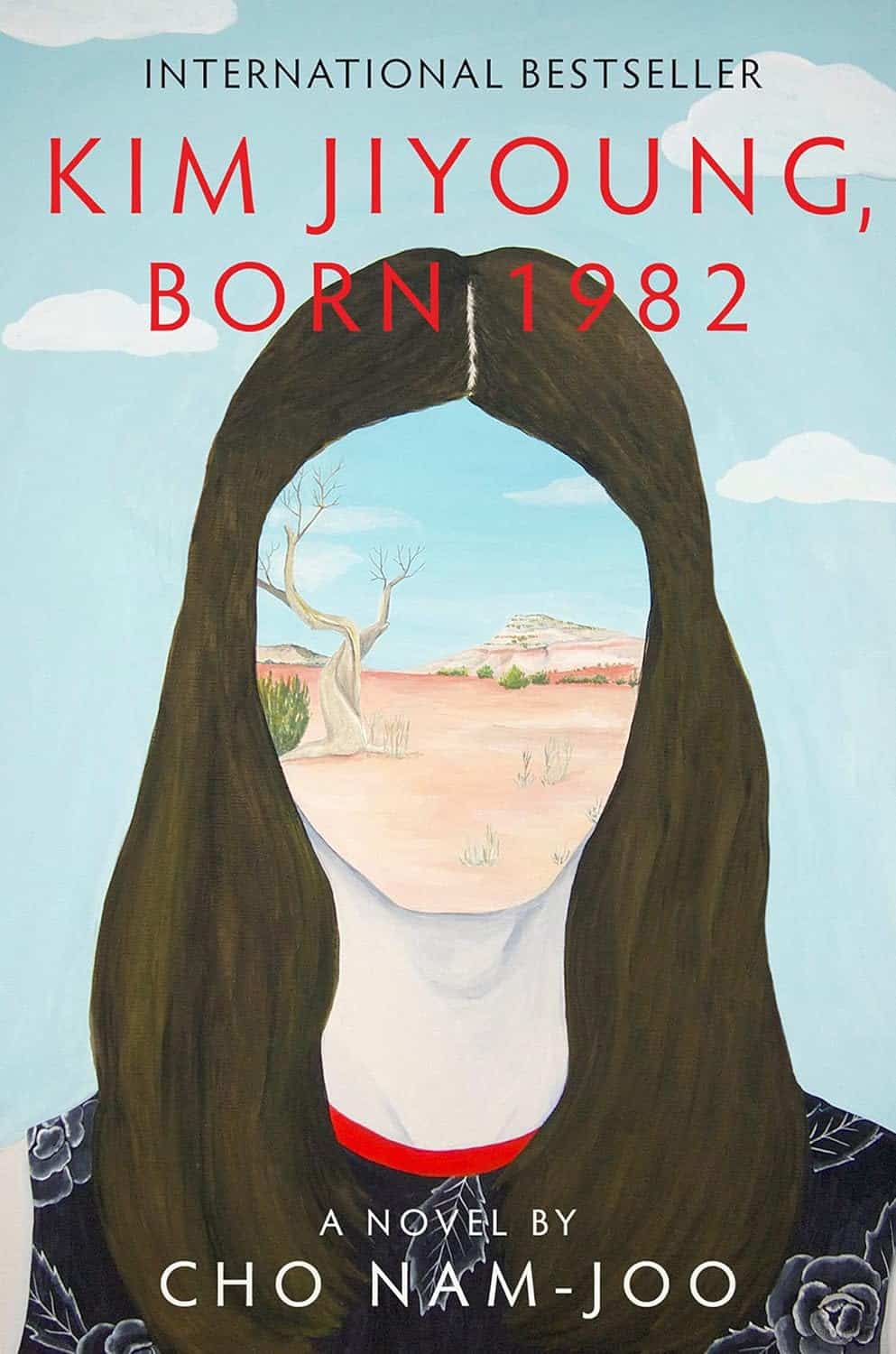

Cho Nam-joo, a former scriptwriter for TV programs took two months to write the story as according to her, the title character “Kim Ji-young's life isn't much different from the one I have lived. That's why I was able to write so quickly without much preparation.” Published by Minumsa in October 2016, it has sold more than 1 million copies as of 27 November 2018, becoming the first million-selling Korean novel since Shin Kyung-sook's “Please Look After Mom” in 2009. It was also the subject of much controversy, as many perceived it as sexist against men. The movie that followed was also successful and controversial.

The story begins in 2015, with Kim Ji-young, a young Korean, mother of one and wife, exhibiting a strange psychiatric condition, of impersonating women she knows, her mother for the most part but also a former classmate who died on birth. After a family meeting during the holidays, her husband decides to take her to a psychiatrist, with the rest of this part, however, coming up in the book in only the last of six chapters it consists of. In between, Cho deals with her life since childhood, also focusing on the life of Ji-young's mother, essentially portraying the consequences of the intense patriarchy of Korean society on women of all ages.

Check also this article

In that fashion, as a kid, Ji-young and her sister have to give everything in order for their brother, the only son of the family, to succeed in his life, from food to their time and everything between. Their father is completely detached from them, only caring about his son, with him only appearing to scold or admonish them. Their mother, on the other hand, who has suffered as them as a kid, seems more understanding, and helps them anyway she can, while also taking care of the financials of the family, against the immature decisions of her husband. As she grows up, Ji-young realizes the imbalance in favor of males in Korean society, starting from school and continuing in the job-finding stage, until the actual work environment, where things actually become worse.

Ji-young has a couple of relationships and eventually gets married to a man who loves her, but still insists on the path she must follow, which essentially has her quitting her job and raising their children, with the first one being a daughter, to the disappointment of various relatives. The pressure however, continues, with her expected to be a loving mother and wife, completely dedicated to everyone but herself, as if she has to follow a kind of dogma. Furthermore, her husband, who obviously loves her, still cannot escape the clutches of patriarchy, with his support always moving towards a specific path, thus showcasing his uselessness to both listen and truly take care of his wife.

Cho Nam-joo's approach is actually detached, with her presenting the story and the resulting comments in a fashion that could be described as clinical, as a kind of report about the blights women face in Korea. Small sentences, simple words, and essentially almost no kind of literary “beautifications” are the rule here. It is this coldness that actually makes the whole novel chilling to read, as much as the fact that she offers no kind of relief, essentially stating that nothing will ever change, in a rather pessimistic approach, that can also be described as pragmatic.

At the same time, and through her presentation of the various men in the book, and particularly her father (the stalking incident is a distinct sample of his behavior) her approach is actually polemic towards the particular sex, which is where the negative comments about the book derived from. Considering what she describes throughout the book, however, and a number of recent documentaries and films that make similar and even worse comments actually, her approach emerges also as realistic, in an aspect that is actually quite appealing. The hoju system, which was abolished only in 2008 and the reports about gender (in)equality (in 2017, the OECD placed Korea in the last position of all OECD countries for gender pay gap) highlight the fact quite eloquently, with Cho actually mentioning a number of them in the footnotes of the book.

Considering the impact it had, even if it was through backlash, one could say that Cho Nam-jo succeeded in her goal with “Kim Ji-young, Born 1982” of highlighting the issues women face in Korea to as many people as possible, in a book that emits both its realism and the author's anger in the most eloquent fashion.