by Bastian Meiresonne

“Cobweb”, Kim Jee-woon's tenth feature film, marks the director's return to comedy for the first time since the beginning of his career. This satire on the film industry is a true cinematic layer cake: one can dig into it with hearty bites for the sheer pleasure of the visual feast, or one can peel it apart, layer by layer, to unveil a fascinating portrayal of the dark period of Korean history in the 1970s and a profound introspection by the director on creativity and the filmmaking profession.

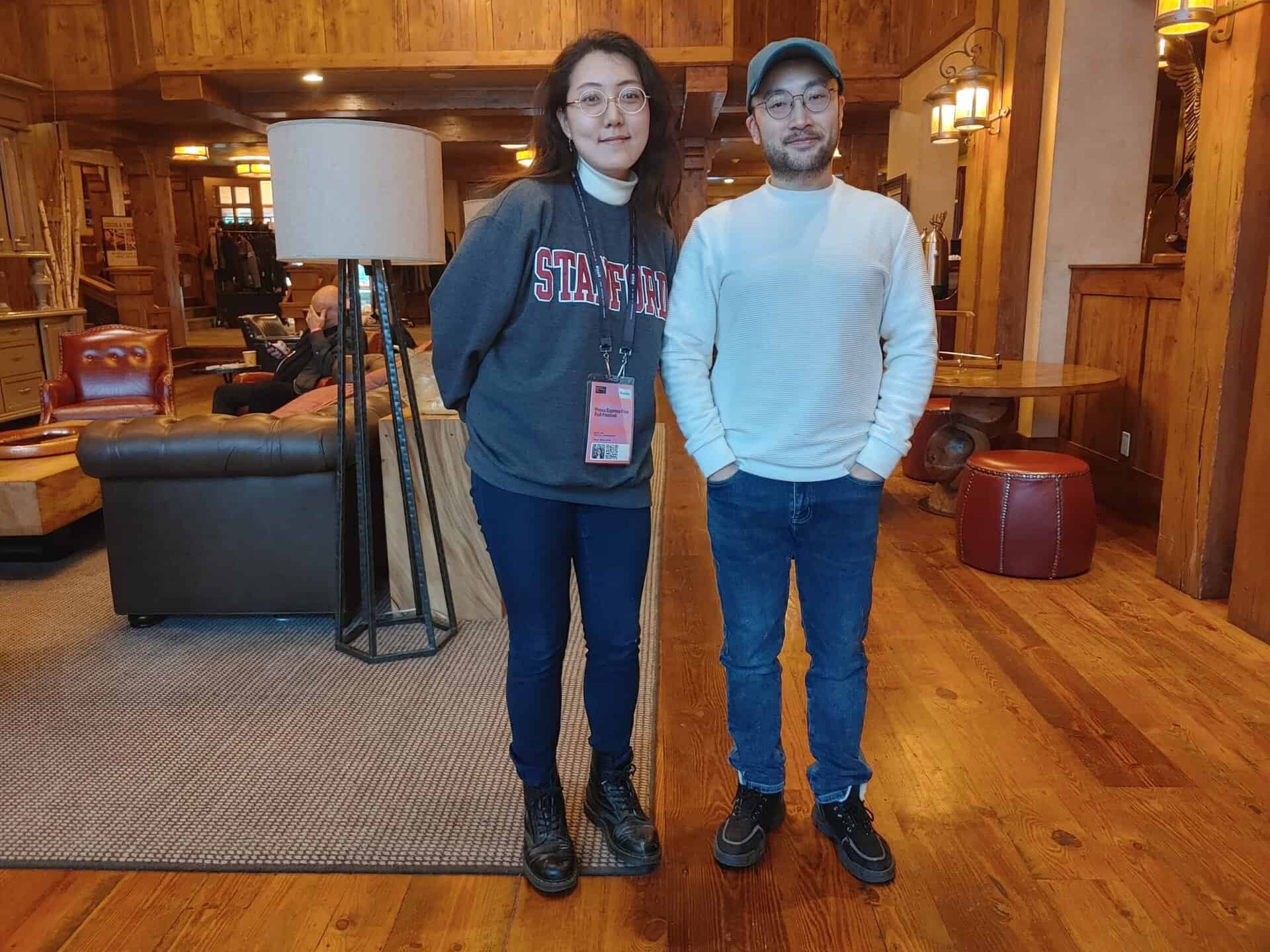

Kim Jee-woon began his career in the 1990s as an actor and a theater director before directing his debut feature film, “The Quiet Family”, in 1998. He is part of a new generation of filmmakers, along with Bong Joon-ho and Park Chan-wook, who no longer followed the traditional apprenticeship model of old studios, but are authentic cinephiles who came to cinema out of pure passion. These future directors grew up during the rise of video rental stores and university film clubs in the 1980s, granting them, for the first-time, unprecedented access to a multitude of films from all around the world.

These filmmakers are nicknamed the “386 generation”: individuals born in the 1960s, who witnessed the socio-political upheavals of their country in the 1980s, and who become directors in their thirties during the 1990s and 2000s. As a result, their films draw from both their fervent passion for cinema and their personal experience of the profound changes in Korean society.

Check also this interview

Kim Jee-woon's remarkable ability to explore multiple genres in order to test their boundaries played a crucial role in the revival of Korean cinema in the late 1990s, inspiring other filmmakers and securing numerous local and global successes. Following his first two comedies, “The Quiet Family” (1998) and “The Foul King” (2000), which intertwined satire, thriller, and horror, he went on to create the fantasy film “A Tale of Two Sisters” (2003), paid homage to Hong Kong-style dark crime films with “A Bittersweet Life” (2005), and embraced the Manchurian action / Korean western genre with “The Good, the Bad, the Weird” (2008). He further ventured into revenge genre with “I Saw the Devil” (2010), delved into historical spy thriller with “The Age of Shadows “(2016), and adapted a futuristic anticipation film from an anime (Japanese animated feature), “Illang: The Wolf Brigade” (2018). These achievements have not only solidified his reputation but also influenced and contributed to numerous local and global successes.

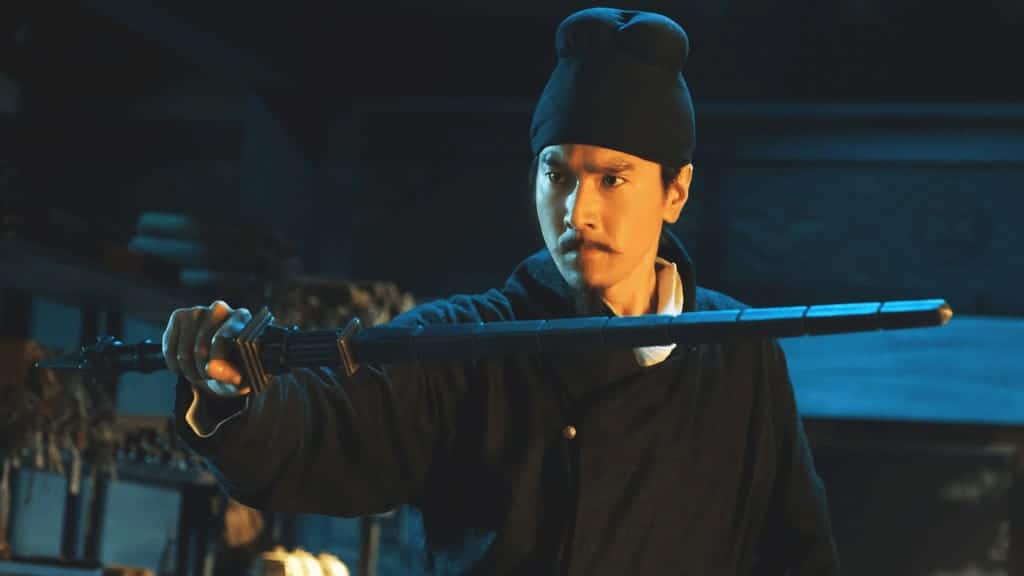

“Cobweb”, Kim Jee-woon's tenth feature film, thus marks his return to comedy for the first time since his beginnings. By exploring the obsession of a filmmaker in 1970s Korea, who is determined to alter the ending of his latest film in a bid to turn it into a masterpiece, he delivers a hilarious satire of the inherent challenges of filmmaking, akin to classics like “Singin' in the Rain” (Stanley Donen & Gene Kelly, 1952), “Ed Wood” (Tim Burton, 1994), “Hail, Caesar!” (Ethan & Joel Coen, 2016), or more recently, “Babylon” (Damien Chazelle, 2022). The plot, filled with numerous twists and turns, takes a humorous look at practically every conceivable misfortune that can befall a director, from overbearing producers and egotistical has-been actors to zealous censors.

Yet, by choosing to set his story in the early 1970s, Kim Jee-woon also paints a captivating portrait of the Korean film industry and society during the dark 1970s. It sheds light on a largely unknown chapter of history on the international stage.

Concerning the movie

- The particular time period

For a better understanding of director Kim Ki-yeol's entirely unusual request to reshoot the ending of his film and the producer's psychosis to avoid upsetting censorship, it is important to place “Cobweb” in the historical context of early 1970s Korea:

Korean cinema officially takes its birth on October 27, 1919, with the release of Kim Do-san's “Fight for Justice”. The challenging period of Japanese occupation (1910-1945), followed by the Korean War (1950-1953), hinders its development. However, a series of tax exemptions introduced in the 1950s encourages producers to invest again in the industry: film production jumps from 15 films in 1955 to 111 in 1959 before experiencing a true golden age in the 1960s, with a peak of 229 feature films produced in 1969, attracting 178 million viewers to cinemas, a record only surpassed in 2012.

In the 1960s and early 1970s, films were produced at a frantic pace, in less than four weeks, from the initial idea to their release in theaters. The most prolific filmmakers of the time, like Kim Soo-yong, Jang Il-ho, and Kim Kee-duk, would shoot up to ten feature films per year. Studios were vast, poorly insulated, and lacking soundproofing; the absence of infrastructure and equipment forced production teams to share cameras and shooting stages.

The stars of that era were extremely busy, often filming up to four movies a day, and learning their lines from teleprompters during the actual shooting. They were dubbed by professionals crammed into the few sound booths available, and were instructed to adopt “high-pitched voices,” often quite different from the original voices of the actors. “Cobweb” playfully touches on some of these anecdotes.

However, the evolution of Korean cinema has always been intrinsically linked to its political situation: on May 16, 1961, a coup led by General Park Chung-hee marked the beginning of a particularly strict military regime (1962-1979). The new president implemented various measures, including a production and distribution system modeled after Hollywood, reducing the number of production companies from 71 in 1961 to four in 1963 and “encouraging” them to favor anticommunist, nationalist, and pro-regime films.

In October 1972, President Park Chung-hee established the “Yusin” constitution, granting him absolute power with unlimited presidential terms. He also intensified censorship: by 1975, 80% of screenplays were subjected to revisions, compared to only 3% in 1970. In this context, film production dropped from 209 films made in 1970 to 96 in 1979.

The plot of “Cobweb” is thus situated precisely at the pivotal period between the end of the golden age of Korean cinema and the beginning of its decline, while also implicitly and ironically alluding to the heavy censorship under the dark military regime of Park Chung-hee.

- Creativity according to Kim Jee-woon

Beyond the fictional satire sprinkled with authentic historical events, “Cobweb” also serves as a captivating personal introspection by Kim Jee-woon into the power of creativity and the director's profession. Hindered from filming during the Covid pandemic and convinced that the world would never be the same as before the crisis, he extensively pondered the purpose of cinema and the role of a film director.

Kim Jee-woon primarily uses “Cobweb“ as an allegory for his own repeated struggle to see each of his projects through against all odds. The character of Kim Ki-yeol serves as his alter ego: he goes from being a celebrated filmmaker for his first feature film to becoming a mere executor of commercial projects. The reshooting of the ending of his latest project becomes a true artistic redemption for him, granting him the strength and energy needed to face all the obstacles standing in his way.

Simultaneously, Kim Jee-woon also delves into what makes a creation unique and distinctive: in his film, the director Kim Ki-yeol starts as an assistant to the legendary filmmaker Shin Sang-ho. His first—and only—cinematic success was only possible because of his mentor; since then, he is churning out commissioned projects from his production studios. The realization of the necessity for reshooting his film at the beginning of “Cobweb“ becomes the precise moment when Kim Ki-yeol finds the strength to finally attempt to break free from the looming presence of his mentor and the repetitive formulas imposed by his producers in order to fulfill his own artistic vision.

This detail offers another fascinating introspection into Kim Jee-woon's own career: not only does he have to break free from the cultural legacy of classical masters (of Korean cinema), but he also has to reinvent the existing. Kim Jee-woon, unlike any other Korean director, has consistently switched genres with each new film. Therefore, he's not merely reinventing stories that have already been told, but he's actually appropriating and reinterpreting cinematic genres to transform them into something innovative.

- Kim Jee-woon's obsessions

As diverse as Kim Jee-woon's filmography is, two recurring themes run throughout his work and reach their climax in “Cobweb“: the first is that of characters systematically trapped in unexpected and seemingly insurmountable situations. “Cobweb“ primarily tells the story of a director who faces a series of misfortunes in order to complete his passion project; however, the film also portrays the individual struggles of numerous secondary characters: the accountant Shin Mi-do, who exerts tremendous effort to see the production through; the producer, Mrs. Shin, who confronts government officials to save her studio; and the lead actor Kang Ho-se, who must navigate the unexpected consequences of an adulterous affair on set.

The second recurring theme in Kim Jee-woon's work is the unspeakable trauma of his characters: they all seem haunted by dark memories that undermine their trust in others. This emotion resonates across many films created by the “386 generation,” including those of Park Chan-wook and Bong Joon-ho: the successive historical periods from Japanese occupation to the fratricidal Korean War, from the military regime of Park Chung-hee to the recent rise of individualistic ultra-capitalism, have gradually generated a profound sense of mistrust among Koreans.

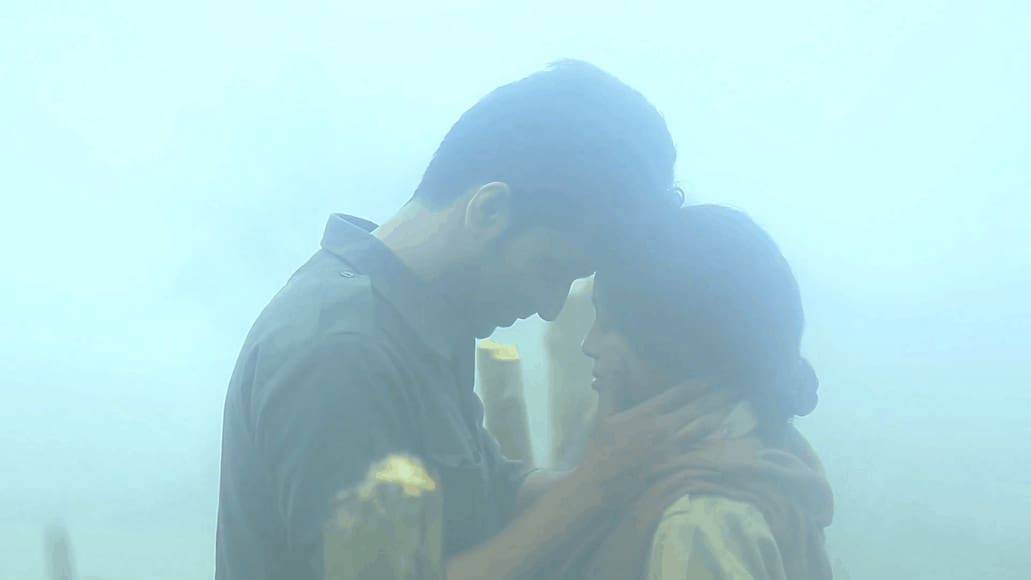

Kim Jee-woon translates this unique emotion literally into images, through the surprising final sequence of the “film within the film” (without spoiler): according to the director, life is nothing but a vast spider's web in which humans are ensnared. Regardless of their conduct, whether good or bad, they will always end up being caught by more powerful forces: by the greed of others, the unpredictabilities of life, or… by a totalitarian regime lurking in the shadows, akin to a giant spider.