Based on Ueda Akinari's tales “The House in the Thicket” and “The Lust of the White Serpent”, “Ugetsu” is set in Japan's civil war torn Azuchi–Momoyama period (1568–1600) and is probably Kenji Mizoguchi's most celebrated work, and a definitive part of the Golden Age of Japanese films. The movie was restored in 2016 by The Film Foundation and Kadokawa Corporation, in the version we watched in Thessaloniki.

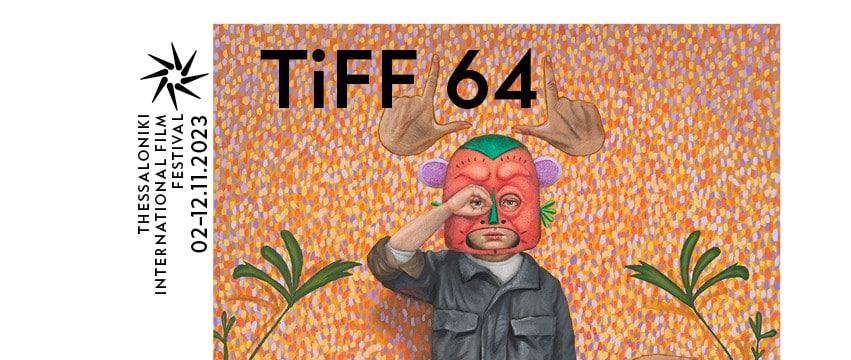

“Ugetsu Monogatari“ is screening at Thessaloniki International Film Festival

On the shores of Lake Biwa in the Omi Province, Genjuro, husband of Miyagi and father of an infant son, has his first break with selling his pottery in Nagahama, making a small fortune in the process. His brother-in-law, Tobei, is eager to become a samurai, and during the same trip is utterly disgraced, eventually agreeing to help Genjuro with his pottery instead of chasing his crazy dreams. Right before the next batch is made, the area is attacked by Shibata Katsuie's army, who pillage and rape in their mad path. The two families barely manage to escape, but decide to take the last batch and sell them to the next town across lake Biwa. As they leave their village, they are met by a boat, whose sole passenger warns them to go back, before he dies. The men decide to send their wives back and proceed to sell Genjuro's merchandise in the market. They sell well and Tobei takes his share and tries to fulfill his dream. Meanwhile, Lady Wakasa, a noblewoman, shows interest in Genjuro's products and invites him into her home.

Check also this interview

The reasons “Ugetsu Monogatari” holds the place it does in world cinema are quite evident, and actually extend to both context and cinematic approach. Regarding the second, and considering that the quintessential purpose of cinema is to record movement, it is simply wondrous to watch how Mizoguchi includes essentially constant motion in every scene, either by the actors or the surroundings, as in the case of the waves of lake for example. Furthermore, some of his most renowned scenes are included here, with the help of cinematographer Kazuo Miyagawa. The first of those scenes occurs in the very beginning of the film, as the camera pans across the landscape, in the fashion of traditional Japanese scroll painting, in one of Mizoguchi's most distinct characteristics. The second and most famous one is the scene in the lake with the boatman. The scene was partly shot in a tank with studio backdrops, but the cinematography and motion is so perfectly implemented that the scene looks 100 percent natural.

If one was to find a fault in that regard, it would probably be the music, whose almost constant presence does become annoying after a fashion, particularly when the wind instruments are especially loud.

Regarding context, the most obvious trait here is how Mizoguchi manages to masterfully combine a war/family drama with a ghost story, in a way that actually appears quite natural, even when the revelations come to the fore. Apart from this, the movie thrives on context on various levels. The blights of war are evident throughout, with the filmmakers holding very few punches in the barbarism, cruelty, inhumanity and decay the people who are involved in are bathed in, with the scenes of killing, stealing, and rape presented in abundance in the movie. That the supposedly glorious soldiers were actually people who barely had anything to eat adds to the remark, in a rather pointed, as much as realistic comment on both war and the whole concept of the samurai.

This approach is mirrored also on Tobei, whose dreams of samurai glory are presented as sheer buffoonery, with his rise and fall stressing even more the ridiculousness of the whole concept. Eitaro Ozawa is exquisite in the role, with him portraying the kind simpleton with gusto and a very fitting hyperbole throughout the movie. Masayuki Mori as Genjuro is equally good, with his character presenting another set of comments, this time dealing with blind ambition, lust, and the constant pursuit of riches, which is why essentially he ends up the one receiving the most severe “punishment” in the movie, although Mizoguchi takes care of not destroying him completely, essentially on the benefit of his virtues (loving father, dependable, etc), in an aspect that moves towards crime and punishment territory. Gorgeous Machiko Kyo as Lady Wakasa is the one who steals the show though, with her arc being the one that moves into the supernatural in the most entertaining way, while also highlighting another aspect of the consequences of war. Lastly, the whole story seems to send a more subtle message, about the blights that befell people when families are split, with the fate of all involved highlighting this remark in the most obvious fashion.

Despite its melodramatic base, however, Mizoguchi definitely avoids the reef of forced sentimentalism in a number of ways. The ghost story aspect, the subtle but intelligent humor and the mocking of samurais, and the somewhat optimistic ending that seems to state that people heal and life goes on even after intense tragedies, all move towards this direction, in another great trait of the film overall.

“Ugetsu Monogatari” is a definite masterpiece, a movie whose messages and cinematic approach echo rather significantly even today, and a title that has definitely stood the test of time, with the restoration helping significantly in that regard.