Having graduated from Busan's Asian Film Academy in 2007, Chia Chee Sum (nicknamed Darrel) took his time to hone his patient craft. In 2018, he returned to the South Korean city to present “High Way” (2018), which won the Busan International Short Film Festival's Jury Prize. His gently observational, frequently amusing short film, about a young motorcyclist's hunt for his T-shirt along the corridors of a public-housing flat, was soon followed up by the China-set diaspora short〈烏達烏達〉“Otak-Otak” in 2019.

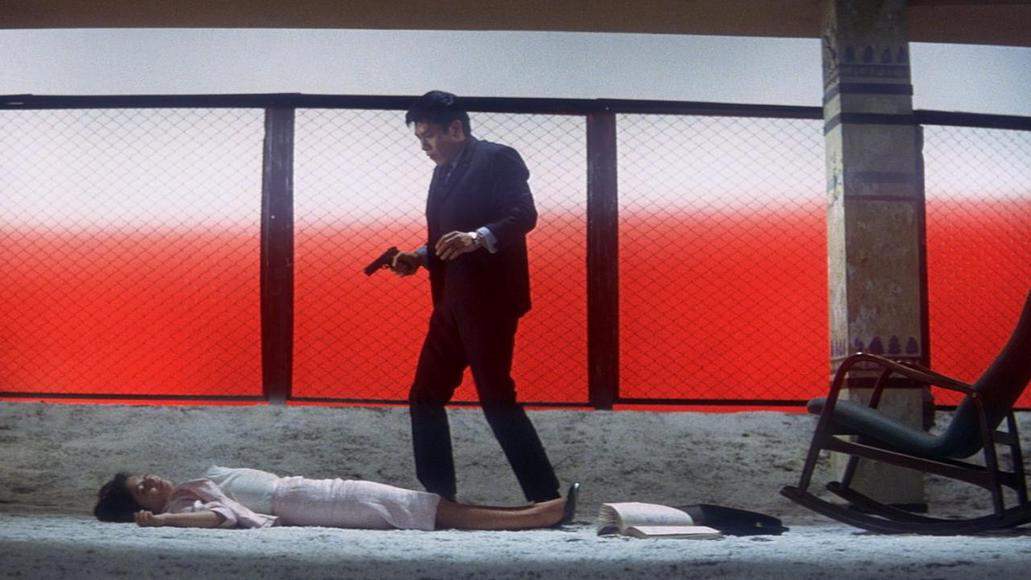

In October 2023, Oasis of Now competed in the New Currents section of Busan International Film Festival, where it was hailed as “the most beautiful film of this Busan competition”. Situated entirely in a crumbling apartment complex in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, where Chee Sum lived, his first feature drops in on the clandestine meetings between a Vietnamese mother, Hanh, and her increasingly distant daughter, Ting Ting. Hanh happens to be an undocumented domestic worker; her young girl is fast integrating into Malaysian society—both yearn for a loving, better future.

A Malaysia-Singapore-France coproduction, “Oasis of Now” has gone on to screen at the Jio MAMI Mumbai Film Festival and will be in the main competition of Indonesia's Jogja-NETPAC Asian Film Festival. Over a video call from Busan, the filmmaker shared about his cinematic relationship to place and time, plus sound and silence, and “fun ways” to improvise with his actors.

Congrats on your debut feature premiere! How was your Busan experience?

Personally, I was really nervous, lah. But after the three screenings and Q&As, I felt very relieved that the audience stayed on and asked a lot of constructive questions. They were very curious about the film and the process of making it. I'm happy that out of all the questions they asked, they never asked about how the main character [Hanh], an undocumented migrant, is victimized. I'm happy that they see her as a person. It's my intention to strip off all these labels and try to see her as a person first.

“Oasis of Now” largely takes place in a Kuala Lumpur apartment block you used to live in, “a place”, you write in the press notes, “that has made me feel both close and distant in various ways”. What memories do you have of that building and how did that influence your film?

The apartment we shot in is where my stepfamily still lives. I first came to this apartment when I was around 9 or 10 years old. My relationship with my stepfamily is alright, and they're kind people, but for me, sometimes you want to be close but you're not sure how to do that. You have to keep some distance.

We shot next door to my step-grandma's unit, but even until now it's a space that makes me feel close and distant. My late step-grandpa, a Hainanese, was quite conservative. Because I'm not blood family, there was this strangeness about including me in family photos. So, whenever I knew they were about to take photos, I would go out to play in the corridors and the staircase you see a lot in the film. It was to avoid that awkward moment. My stepfamily would still know that I'm around, and I could still hear the sounds and voices from the house, but I didn't need to show my face. That's the feeling that I'm trying to portray in “Oasis of Now”. All these little memories and experiences that make me feel like we want to be close but should have a bit of distance.

Your short films, too, take place in pretty brutalist buildings, often corridors in public-housing flats. Many directors respond to architecture, but I'm wondering why you seem to be drawn to microenvironments—interior-exteriors, essentially, like staircases—and set your films in single locations?

I've lived in many different homes, so for me it starts with space. I think in images, not loglines or synopses. From location scouting, I look for a subject, then it's very easy to work out a story and scene.

Before “High Way”, frankly speaking, I made a lot of shit short films. Stain of my life! I was always trying to make something I was not familiar with. I didn't have a clear idea of what I wanted to make, and I wasn't sure if I could continue making films. So, I took a break from my commercial work and other projects, and I just told myself to make something very simple, as a test for myself, from the place I'm familiar with. That apartment block was where I lived for a long time with my maternal grandfather. I looked for subjects within this space. I was curious how my characters work with this space. And it was only through this that I realised it was so simple: just do something you know.

For “Otak-Otak”, a project I did during FIRST [International Film Festival] Training Camp, I continued to make a film based on location and character interaction with it. To be honest, I wasn't so confident because I didn't live there [in Xining, western China] and wasn't familiar with it. Also, most of the Chinese immigrants to Singapore and Malaysia came from the southern part of China. The story is based on my late grandfather's experience.

With the three films, there are not many establishing shots. I still can't find a way to use exterior cutaways. Maybe because I try to make things as tight as possible. Sometimes, when I design a story with many different locations, it feels like I'm watching different films.

Though “Oasis of Now” only uses end-credit music [by Teo Wei Yong], the soundscape throughout is its own soundtrack, too. It brings me to a hot, still afternoon in Southeast Asia where nothing and everything could happen. How did you create this sonic world?

We [sound designer Ng Chor Guan and I] worked with re-recording mixer Laure Arto [“Mariner of the Mountains”, “The Sacred Spirit”] from France. I remember after the first time Laure watched it, she mentioned “touches”, that the sound doesn't need to be too much or noisy. There are many close-up shots of hands in “Oasis of Now”. Even medium shots of characters touching or almost touching each other. Those are the things that she wanted to enhance.

I told her that I wanted the sounds to be like … you know how sometimes when you're in a cinema and it goes very silent, you feel like you're being sucked into the screen? Or how, because of certain bass or certain foley movements, you're being touched? I don't know how to describe this sensorial feeling, but these are the emotions I want to convey with cinema: it's not about the words or dialogue, or whatever image, but using different elements—visuals, sound, silence, touches—together to move.

Your actors delivered such naturalistic performances, especially Ta Thi Diu, a nail artist who plays Hanh, former village chief Abd Manaf Bin Rejab (Azmi), and child actress Aster Yeow Ee (Ting Ting), who's the only professional among them. Could you share about how you found and worked with them?

Because of the pandemic, we couldn't cast in real life, so I found Ta Thi Diu on Facebook through my Vietnamese friend, who's the inspiration for some of the character of Hanh. Over more than a year, we got to know each other, built up trust, and shared personal things like her family situation. Her personal experience allowed me to relate to her, and linked her to the character, which allowed me to blend them together and recreate some scenes based on her life.

Abd Manaf wasn't the initial actor for this role. During the actors' meet-up, he came with his wife, who's another cast member, and he talked a lot. Everyone naturally listened to him like he's a wise man, and in real life a lot of migrant workers look to him for help. So, he turned out to be a perfect fit for the role.

I don't let the actors see the script, only the crew. Each day, the cast doesn't know which scene we're going to shoot; I tell them right before we roll. I create a circumstance for them, and they respond to it. There are many fun ways to improvise. For example, for the scene at the staircase where the mother meets the daughter, I briefed the actors separately. I told Ta Thi Diu that your daughter will be waiting for you there happily, play along with her. Then I asked Aster: if your real-life mother doesn't like you, how would you react? She said, I would take my bag and run away. I'm hoping for a surprise reaction that I can't direct, for them to speak in their own way and be themselves, instead of memorising lines. But it's quite a risky and time-consuming method; usually only one or two takes are useable—that's enough for me. I've been working this way since “High Way”.

You developed “Oasis of Now” during the pandemic, winning development awards at Locarno Open Doors and Talents Tokyo in 2020 and SEAFIC in 2021. Did Covid impact its production?

The pandemic held us back, but actually gave us more time to look at the practical side of things: the planning, the team, the collaborators. Honestly, we were very lucky. For someone so low profile as me, I count myself very lucky to have all this support [“Oasis of Now” also won the WCF Europe-TFL Audience Design Award 2021]. SEAFIC helped a lot, there I got to know Raymond [Phathanavirangoon, former executive director of SEAFIC and a producer], Fran [Borgia, Singapore producer of “Oasis of Now”], and Franz [Rodenkirchen, script advisor]. I wanted to give up during the first SEAFIC session, I can only imagine how shit my script was, but Franz was the one who really listened to me and helped me find my voice.

You describe “Oasis of Now” as your and the lead character's “attempt to open up … sharing our personal feelings”, and that “genuine closeness hinges on the extent to how we are seen or not seen by others”. What do you hope to leave your audience with?

I don't know if this sounds cliched, but it will be enough if, just for a very short moment—a moment that you know cannot last, or be extended in this society—you can see someone—a stranger, a family member, anyone—without any labels. When you try to understand someone, you need to know about someone's background, and the more you know, it's sometimes hard not to judge them based on your own personal experience and will. I know having a stepfamily is not very special, but sometimes when I see strangers, they look like family to me. When I walk next to a stranger, I get a strange feeling that this person could be someone close to me.

That's why, for me, being seen in itself, as a person and as a gesture of acknowledgement, without any words, is good enough. A small gesture like this is quite nice already lah.

Thanks to Raymond Phathanavirangoon and Fran Borgia

Author: Dan Koh

FB and IG: @damnkohl

Bio: Dan Koh is the author of Jurong, My Love (2017), a Singapore Unbound Book of the Year. His essays and articles have appeared in books published by The MIT Press and Weiss Publications; periodicals like BiblioAsia and Time Out Singapore; and websites such as Vdrome and ArtsEquator. He is currently a writing fellow of the inaugural ArtsEquator Fellowship 2023–4 and is also a book editor and film producer. Dan's website is damnkohl.com.